Silicon Alleys

When it comes to contemporary American classical music composers, John Adams is probably the most widely performed while at the same time the most provocative and criticized. To this day, his 1990 opera, The Death of Klinghoffer, about the Achille Lauro hijacking in the Middle East, causes political and emotional trauma whenever it’s produced. Other stage works like Nixon in China and A Flowering Tree have sent critics and purists into uncomfortable tizzies worldwide.

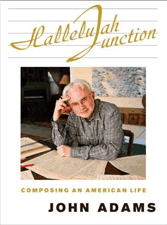

Now Adams has crafted his own memoir: Hallelujah Junction: Composing an American Life, in which he lets us right into his head and provides a snapshot of his own creative machinery in refreshingly straightforward and practical language—something most composers can rarely do. In fact, many of them dread even being asked where “the ideas come from,” primarily because the very question is so drearily uncreative. But Adams provides a worthy explanation:

The composer’s mind is like flypaper, ready at any moment to attract and trap an idea, a single sound or a complex of sounds. It may be the rhythms of a group of people chattering in a restaurant, or the Doppler effect of a passing train, or three notes from someone else’s song, be it Mahler’s or Otis Redding’s. Or an inspiration might arise from half-consciously diddling with some piece of technology. We need to foster and jealously protect the ‘what if’ mode of creative play, taking delight in moving sounds around just for the pleasure of seeing and hearing what might happen. The point is to maintain a childlike openness, not to foreclose on a possibility because it does not immediately fit your preconceived notions of what the piece you wish to compose ought to sound like.

That’s often exactly how I write this column, misfires included, and I guess I have Adams to thank for helping me sort out the potential of my own future material. That said, we now come to another local native influenced by Mr. Adams. A version of his opera, Doctor Atomic, concerning the final hours leading up to the first atomic bomb test in New Mexico, is currently undergoing a run at the New York Metropolitan Opera.

The controversy this time around centers on the taboo use of amplification at the Met—a phenomenon previously unallowed by that institution throughout its 125-year existence, primarily because opera purists insist that the use of microphones “corrupts” the art form. But thanks to Adams’ longtime collaboration with sound designer Mark Grey, an SJSU grad, all of this has changed.

Grey is both a composer and an audio engineer—a rare combo these days—and in his work with Adams since the mid-‘90s they have proven that intricate acoustic analysis specific to the venue, along with subtle and sensitive use of speaker layouts, can be an important element of the opera production, especially since many of Adams’ works utilize both electronic sounds and acoustic instruments, thus demanding an unconventional approach.

The purists will be scratching their heads on the way to the glue factory, but I predict that 10 years from now—maybe even five—everyone in the opera community will look back on the composer/engineer collaboration between Adams and Grey as a major turning point in the evolution of the concert hall listening experience.

Grey and I were co-conspirators, gig-mates and fellow SJSU Spartans. We once helped organize a colossal mess of a gig in Morris Dailey Auditorium in 1996, when we were one of the first to use an Asynchronous Transfer Mode network to broadcast the audio and video of live performers to CSU Monterey Bay, while performers there did the same in reverse. And now, 12 years later, he is the first one to use microphones at the Met for Doctor Atomic, which will be broadcast live in high definition to cinemas across the States this Saturday. Hail, Spartans, hail!

DOCTOR ATOMIC, by John Adams, will be broadcast live from the New York Metropolitan Opera on Saturday, Nov. 8, at 10am at CinéArts, Santana Row, 3088 Olsen Dr., San Jose. Tickets are $24 adults/$16 children/$22 senior. (408.554.7010)