There is a proposal coming soon to the San Jose City Council called Opportunity Housing — a blanket upzoning of all neighborhoods in the city. While well-intended, I urge my colleagues to reject it.

This hastily-thrown-together and misguided policy is the product of an out-of-touch political establishment that is not listening to the community. Instead of producing real solutions to build more housing in a sustainable and scalable way, City Hall wants to find the easy way out. There’s a better way.

Let me begin by setting the record straight. We have a regional housing crisis — and we need to build more housing. In San Jose alone, we’ve planned to build over 120,000 new units by 2040 to meet regional housing demand and control costs. (And to really address this crisis, we need all other Bay Area cities to put forward equally ambitious plans). There is a tremendous amount of work to be done to create a city we can all afford to live in.

City Hall apparently doesn’t want to do the work, however. Instead of proactively facilitating housing development in transit and infrastructure-rich parts of the city, they’re giving up. This proposal is basically shrugging one’s shoulders and saying, “just put it anywhere.” We can do better than that. From an environmental, economic and equity perspective, we must do better than that.

Increasing density in the periphery of the city would be an environmental disaster in the long run. With more cars on the road having to commute to virtually everywhere, we’ll experience traffic gridlock like never before. There simply is not enough public transit infrastructure in San Jose’s suburbs. In fact, in the last few years, VTA has ended service to 2 of the 6 stops on the only light rail line serving our district, has twice proposed removing the last bus line serving the 40,000 residents of Almaden Valley and has cut back service in Berryessa, East San Jose and Evergreen, all residential-heavy neighborhoods outside of the city’s urban core.

Disappointingly, two months ago I received a report from our Department of Transportation that — for the foreseeable future — assumes no transition from cars to alternative forms of transportation in many San Jose neighborhoods — and roughly half of District 10 — because it projects virtually no investment in the necessary infrastructure in those neighborhoods. Our transportation plan is focused, prioritizing investments in areas with the greatest potential for reducing car use. Our housing plan should do the same.

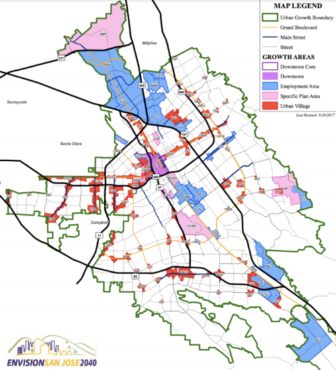

Thus, this proposal will inevitably increase average Vehicle Miles Traveled, or VMT, which is the total distance San Joseans are driving and is one of the most important local measures of environmental sustainability. Already, over 60% of San Jose’s greenhouse gas emissions are generated by transportation. As you can see in the city map showing, development in areas in red would cause an immitigable rise in VMT. Until transit infrastructure and service levels catch up, we should not densify neighborhoods on the edges of our city — for the sake of our air quality, health and the fight against climate change.

A one size fits all housing policy fits no one at all. By promoting four-plex development in lower density neighborhoods, the communities most likely to bear the brunt of this policy are low-income ones; it is most profitable for speculative developers to tear down cheaper homes in poorer, marginalized areas. In this unpredictable four-plex lottery, only those lucky enough to have the market work in their favor can retain their suburban neighborhoods. We need structured, smart growth, not more opportunities for displacement.

While redlining and other historical restrictions on who could purchase homes in certain single family neighborhoods were undoubtedly born of racist intent, the solution today is not blanket upzoning. In fact, careless upzoning policies can result in even greater segregation and displacement, as experiences in New York city and many other cities in recent years have shown. Given this, we should focus on policies that cause the least harm (in terms of vehicle miles traveled, displacement, etc.) with the greatest benefit (in terms of housing and job production) possible.

I understand the good intentions behind wanting to undo single family zoning in the name of racial justice, though I’d also like to point out that we’ve already begun that experiment. Across our entire city, homeowners can now add one and often two backyard accessory dwelling units (known as ADUs or backyard cottages) and even convert garages into living spaces. This year, the city is on track to receive over 1,000 permit applications for new ADUs. This is a significant experiment, one that will further strain overstretched and poorly maintained suburban infrastructure in places like District 10, and one that we should fully run and analyze before we even consider doubling down — or perhaps quadrupling down — on density everywhere.

There’s a better way.

That’s why I’m introducing Smart Growth San Jose: my plan to densify our urban core and transit corridors to build the housing we need, without incentivizing developers to indiscriminately scatter four-plexes across the city.

Here’s what I’m proposing:

Downtown map shows General Plan for the City of Jose.

The city has identified 68 urban village sites that can accommodate new homes without creating traffic gridlock because they are close to jobs, retail and transit infrastructure. These are the places we want to focus development because they can provide density with less gridlock, housing with less displacement and growth with less contribution to climate change. The city map shows where designated urban villages are located in San Jose. The city’s General Plan 2040 maps out where the city can sustain significant growth in housing and jobs, providing for an estimated increase of 120,000 new housing units and capacity for 382,000 jobs, primarily downtown, in North San Jose and within the other 68 urban village areas across the city.

Our General Plan underwent years of review, countless hours of expert staff analysis and feedback from thousands of residents. It is a solid roadmap to follow as we grapple with continued economic and population growth. The problem is that we’ve completely failed to execute the roadmap. We’ve identified areas that can and should sustain smart growth, while maintaining numerous barriers to building housing in them.

These barriers include unnecessary regulations, overly bureaucratic processes, the risk of spending millions to put forward a project only to have it rejected, individual and slow environmental reviews for pro-environment investments like transit-oriented apartment projects on already developed parcels and other government-created barriers. In fact, current city policy actually prohibits building housing in many urban villages at this time, instead requiring that office space be built first, which of course increases the need for housing.

In all, despite designating 68 urban villages on paper, the city’s planning department has only approved 13 of them over the last 10 years and, even in those, hardly any shovels have broken ground. Rather than spend significant staff time trying to implement a controversial and unproductive citywide upzoning policy that will likely generate more problems than it solves, our limited planning staff should double down on removing the many barriers to executing an urban village strategy that is our best hope for addressing a challenge of this scale.

So what will it take to realize the right strategy for growth in San Jose? How can we achieve a focused, mixed use, transit-oriented strategy centered on urban villages?

First, change the rules on Urban Village development. Instead of making individual projects jump through numerous hoops that can take years and cost millions — we should “pre-approve” project locations, design guidelines, community mitigations, environmental mitigations and other project elements within all 68 designated urban villages to enable by-right development for conforming projects. If developers can build well-designed new buildings near transit while meeting our affordable housing requirements — approval of such projects should take weeks, not years. That step alone will lower the cost of housing by tens of thousands of dollars a door and dramatically speed up the construction of new housing in our urban villages.

Second, make city Hall accountable for providing high-quality service to those who want to build housing and bring jobs to our city. Our Planning Department should set and publish their customer service goals, such as response times for permits applications and inspections. When they are late, as is far too often the case these days, the fees should be discounted or even waived entirely for the applicant. San Joseans work hard to earn their paycheck; their government should do the same.

Third, invest in people and innovation to bring down costs. There are simply not enough qualified workers to build the new housing we need and the way we build housing hasn’t fundamentally changed in hundreds of years — we build it all by hand, on site, one nail and one 2x4 at a time. We need more trained workers in the building and construction trades and we need to adopt new technologies like modular construction and 3-D printing that can dramatically lower costs. Research shows that the average American worker is 2.5 times more productive than they were in 1950. We have not seen such gains in the construction industry. We have a shortage of skilled workers and a deficit of innovation, and together that contributes to a high cost of housing.

Local government can help — now — by offering training at our community colleges so workers can spend a year learning the skills they need to enter the construction trades. The return on investment of such a program will be profound — it will lower the cost of housing, put people to work and make our city more equitable by employing marginalized groups historically excluded from the trades.

We need to use our buying power and incentives to jump-start building innovation — like offering even faster permitting and rebates for projects that use technologies like modular construction or 3-D printing. Researchers estimate that modular or factory-made units, produced off-site, can save up to 20% on the cost of building a standard multifamily development while shortening construction timelines by up to 50%. The city should leverage its considerable annual investment in publicly subsidized, affordable housing to facilitate the transition to more innovative construction methods.

There are countless other things we could try: We could build a “development dashboard” to track every project in the pipeline, understand how many days it spends at each stage in the process, and hold ourselves accountable for getting from proposal to shovel-in-the-ground faster than any other city. We could assign a single success manager to each proposal as it comes in and empower that person to move projects forward. We could build a cross-functional team, with staff from every department involved in planning and building and task them with streamlining our development processes. We could limit how much discretion the city Council has over the details of every plan. We could simplify our myriad fees into a single, universal fee that is timed at project completion and tied to project cost to improve predictability and incentivize cost controls.

None of these are new ideas, but none of them are getting sufficient attention either. It’s time to focus and execute. We spend far too much time debating small ideas and far too little following through on the big ones that can make our city better.

At the end of the day, a one-size-fits-all upzoning of an expansive, sprawling city like San Jose that already has some of the worst traffic and least effective transit in the country, is a flawed approach. For every additional person it houses, it will put another car on the road, more time on our collective commutes and more pollution in our air. It will incentivize redevelopment and gentrification of lower income neighborhoods without yielding the level of housing production we need. Ultimately, it will distract our Planning Department from executing on a sustainable, transit-oriented strategy that can work at scale and improve our collective quality of life. We need real solutions that both work and bring people together.

Opportunity housing fails on both fronts, but there is a better, pro-housing path forward. A way that makes room for future generations, offers choice to people of different walks of life and at different moments in their life journeys, and allows a greater number of us to gradually transition from car-dependence to more walkable and bikeable urban neighborhoods. This is a positive vision of San Jose’s future. One that is scalable, sustainable and can offer something for everyone. This is the future we should be fighting for.

Matt Mahan is th e 10th District council member for the City of San Jose.

e 10th District council member for the City of San Jose.

If the proposal is to create Village Plans for the rest of the 55 Urban Village Areas which don’t have a plan, this proposal makes way more sense than opportunity housing.

Besides design standards, the Village Plans need to include new and appropriate zoning and development standards such as transitioning building height away from single family residential zones and maintaining sufficient property line set backs. There is plenty of building space in the 68 urban village areas to solve our housing and affordable housing problems without ruining our single family neighborhoods.

I’m happy that there are at least a few folks on our city council who can see the folly of this “opportunity housing” nonsense. So thanks Matt Mahan.

That said though let’s quit characterizing the housing market here as a “crisis”. That way we can quit continually reacting in panic mode and our grandstanding politicians can stop running around like headless chickens.

There’s so much San Jose could be doing better. I’m sure every city thinks that for their own account. Whether it’s updating sprinkler systems to keep the parks looking nice, proposed housing plans (that work), or something else. I just hope everything gets better.

I wrote a comment to this article but, the ‘cancel culture’ at SJI quashed my response.

David S. Wall

has anyone noticed that the more”affordable” housing that gets built the need for such increases?

there will never be enough affordable housing. Why?

the entire world has a housing shortage. Notice the immense migrations of people moving from one area to another. they need housing. we are asked to house the 200,000/mo Southern border crossers. Next, it will be Afghan refugees. We will be asked to house them, all the while we have homeless, mentally ill, drug-addicted and vets living on the streets.

I don’t know what the answer is but building more “affordable” housing only draws more people seeking housing. We are on a hamster housing wheel – chasing something that is un-attainable. Politicans only accelerate the problem gouging out more taxes for “new solutions” that enhance their

appeal while cheapening life for everyone else by cramming people into tighter spaces, ie. “opportunity”, “affordable” re-zoning from R-1, etc

Hugh Biquitous, Well said.