We have an opportunity on Election Day to protect two critical resources that are inextricably linked: open space in our local watersheds and the life-giving water that flows through our valley.

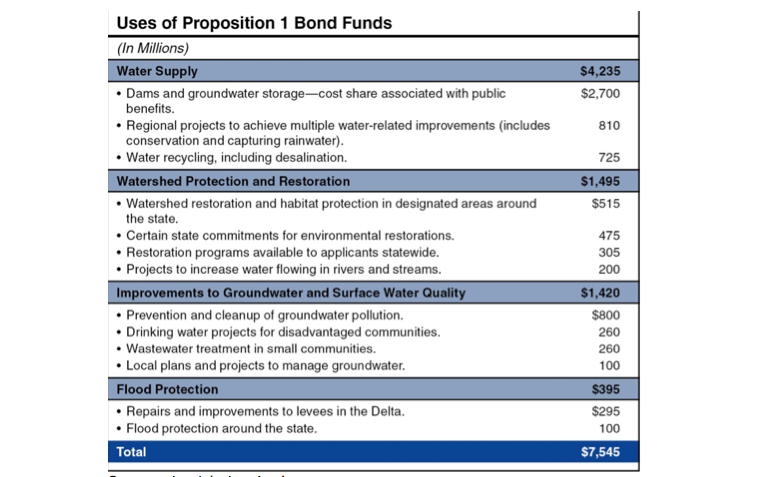

Proposition 1 is a statewide ballot measure authorizing $7.5 billion in bond sales to support various elements of our state's water infrastructure, excluding the controversial Delta tunnels (see table below). Locally, voters can also vote for Measure Q and approve a parcel tax to fund the acquisition, protection and recreational development of open space in our local watersheds.

By passing these two measures, we can reinforce our state’s water supply as well as make funds available to protect our local aquifers from the daily discharge of urban pollutants that continually threaten them.

Source: Legislative Analyst Office

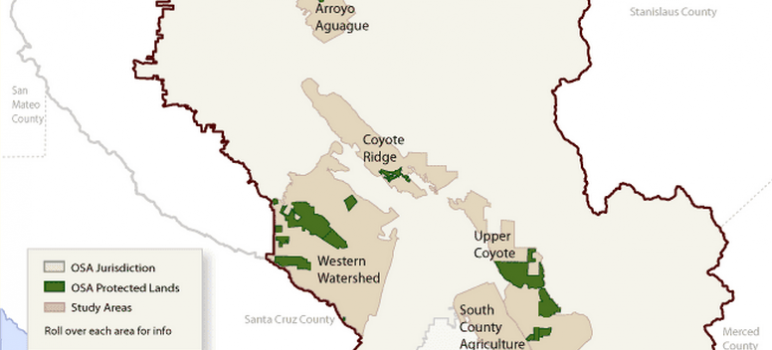

One of the Santa Clara County Open Space Authority’s (SCCOSA) priorities, as stated in their Santa Clara Valley Greenprint is to “Protect our water supplies and reduce pollution and toxins by preserving land around creeks, rivers and streams.” So it’s no accident that one of the 30 proposed projects identified in SCCOSA’s Measure Q is the establishment of the “Coyote Valley Agriculture and Natural Resource Reserve." This project is designed to preserve agricultural lands, enhance natural resources, establish public access and protect a local wildlife corridor. To fully appreciate the importance of this measure, and why we all need to vote for it, a little history is needed.

Silicon Valley—still known as Santa Clara Valley—evolved from a major food production and processing center to an economy based on microchips. With all due respect to intellectual capital, represented by our local universities that seem to churn out an endless supply of entrepreneurs, our natural capital was at least as essential to this valley’s success. And the jewels in that crown are our two adjacent groundwater basins, capable of supplying up to 250 million gallons of water per day.

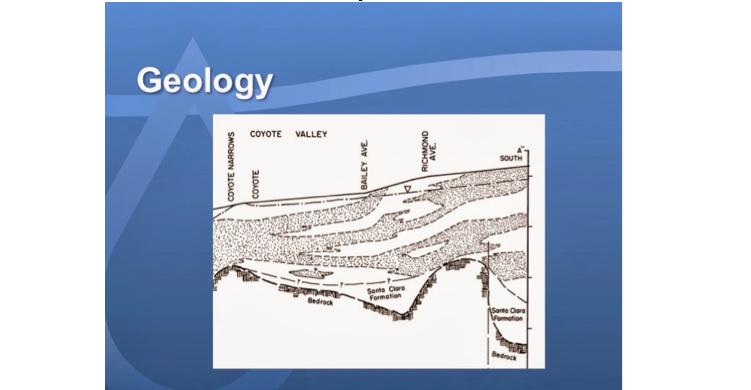

These groundwater basins were formed when silt, sand and gravel eroded from our eastern mountain range into the valleys below. The gravels and larger materials settled out mostly at the top of the alluvial fans, where they are still mined for aggregate to use in concrete and asphalt. The finer sediments were carried further by the surface water and deposited closer to the Bay, where over time they consolidated into a 200-foot deep cap lying over the aquifer. This cap, extending southward from the Bay, protects the groundwater in the northern part of the county, which serves the 13 cities of Silicon Valley.

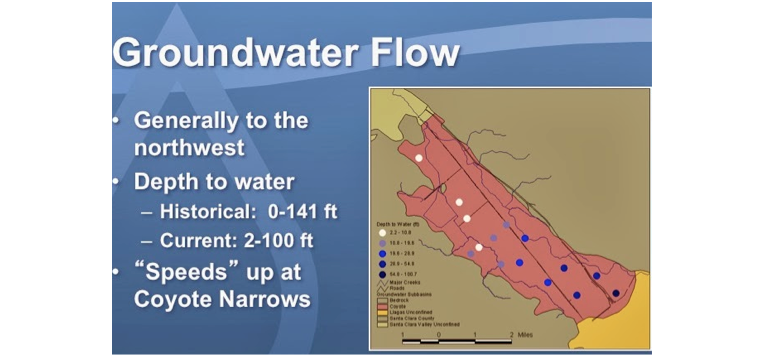

Further south, however, the high porosity of these gravel-filled deposits makes our aquifer extremely vulnerable to contamination from any pollutants that are discharged onto the land or into Coyote and Fisher Creeks that traverse the 10-mile length of the Coyote Valley. Once they reach the usually high groundwater table of the Coyote Valley, pollutants can move quickly down gradient (north) toward the thousands of private and municipal wells serving nearly 2 million people.

The Coyote Valley has been designated as an urban reserve in San Jose's General Plan, with a third of the land at the southern end designated for permanent green belt. Triggers are also described under what conditions a transit-oriented specific plan would be allowed.

Because of the potential for groundwater contamination, San Jose should really designated the entire 7,000-acre Coyote Valley as an Urban Agricultural Reserve and further limit its use to organic methods to avoid the use of toxic pesticides, which would contaminate our drinking water. Restricting development in Coyote Valley to organic agriculture would make San Jose more sustainable in a way that enhances our food security while protecting our water quality—a catchy platform for one of our mayoral candidate’s (although we haven’t heard it yet). It could also be an excellent exercise of the joint powers of the Santa Clara County Open Space Authority and the Santa Clara Valley Water District (SCVWD).

To quote former New Jersey Gov. Christine Whitman, who also served as EPA Administrator under George W. Bush: "Some watershed land simply must not be developed. Its natural value in buffering, storing, filtering and recharging far exceeds whatever commercial value it may hold."

Unless we vote now to protect our upper watershed in Coyote Valley, our water quality will continue to degrade, resulting in the necessity of wellhead treatment at enormous cost, or worse. Ingesting pollutants that find their way into our drinking water can impact health. If we pass both Proposition 1 and Measure Q, we will have a great opportunity to preserve the most vulnerable portions of our watersheds and protect our health, too. Please keep this in mind when casting your vote.

I’m very glad to see Pat outlining how important Coyote Valley is as a groundwater resource and as an open-space resource. From a personal perspective, I spent many years opposing misguided development proposals for North and Mid Coyote Valley that are now defunct. Mid Coyote is now more or less protected from development until 2040 but North Coyote is still vulnerable to sprawl development.

In my current role as a director of the Water District, I’ve seen increased interest in protecting water resources in this area. I was glad that a very recent proposal to build a satellite Gavilan College campus right there, far from urban centers, appears to be on hold. I’ve seen increased interest in high-value agricultural crops supported with recycled water there, and the Cinnabar Hills Golf Club above the Coyote Valley floor is switching to recycled water instead of drinking water for their links.

Passing Measure Q wholeheartedly, and passing Prop 1 despite a few warts, will do a lot to help our local water and local open space.