A man in a gray hoodie and flannel pajama pants strolls casually along the walkway. As he nears a mother and her young daughter, he lunges, snatching the woman’s purse, pulling her and the girl down a stairwell to the concrete.

In a flash, he disappears from the frame.

San Jose police canvass the area surrounding the two-story office complex off of Towers Lane on the East Side. Using private security camera footage, they reconstruct the crime and identify the suspect’s getaway vehicle, a black Lexus sedan. Detectives ultimately match the purse-snatcher to a string of similar incidents, and five days later the police have their suspect.

On May 11, San Jose police arrested 26-year-old Pablo Cabrera Jr. at his home in San Jose. A search of the premises turned up evidence connecting Cabrera to similar robberies of Asian women carrying pricey purses. He was booked at Elmwood jail on suspicion of robbery and violating a burglary conviction parole. The video footage proved crucial to cracking the case, which has yet to go to trial.

Security video helped authorities track down Joey Vicencio, the 21-year-old Santa Claran charged with attempted murder after 10 rounds from a semi-automatic rifle were fired into the Martin Luther King Jr. Library last month. Citizens’ footage also provided clues that led to the identification and arrest of Carlos Arevalo-Carranza, the 24-year-old accused of murdering San Jose resident Bambi Larson earlier this year.

“We have solved homicides, sexual assaults and shootings with the use of surveillance cameras that are privately owned,” SJPD Police Chief Eddie Garcia says. “In the Bambi Larson murder, if it weren't for stitching those neighborhood camera videos together, I don’t know where that investigation would be.”

Obtaining such video evidence is time-consuming. Officers have had to go door to door, asking for permission from individual camera owners or obtaining a search warrant from a judge. Had SJPD obtained the footage of Cabrera, Vicencio and Arevalo-Carranza sooner, they might have avoided days of searching for suspects.

Law enforcement now has a shortcut to such footage. San Jose, Santa Clara and Milpitas police departments recently became the first agencies in the South Bay to use a new virtual tool, which allows detectives to easily obtain privately-owned security video.

The Neighbors App, created by the Amazon-owned networked doorbell and home security camera maker Ring, connects users to security videos of suspicious or criminal activity in the surrounding community. The service is billed as “The New Neighborhood Watch” in ads.

The Amazon subsidiary has also created a “Law Enforcement Portal” that allows investigators to request home-security videos from residents through the app.

Since launching its Law Enforcement Portal for the Neighbors App in the spring of 2018, the digital doorbell company has teamed up with more than 400 police departments across the United States.

The partnerships between local law enforcement and Ring raise concerns about privacy—and the creeping corporate sway on public policy. Civil liberties advocates sound alarms about Ring’s terms of service with police, warning that local law enforcement has become a promoter of an e-commerce monopolist that already has huge stockpiles of personal data, including groceries purchased, shows watched, books read, music enjoyed.

Corporate PR

Under its agreements with San Jose and Santa Clara, Ring can control the content of press releases about the police departments’ partnerships with Ring. The company also expects to approve any Ring-related public service announcements from Santa Clara PD. Even SJPD’s social media posts are scripted by Ring. Gizmodo and Vice have reported similar PR arrangements between Ring and police departments in jurisdictions in other parts of the country.

“It’s very concerning when an enormous corporation is writing the press releases for the government. People think their police department is speaking, when in fact, it’s Amazon that’s speaking,” American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) attorney Jacob Snow says. “It’s using police departments as the mouthpiece for a giant corporation.”

San Jose Inside obtained records that illustrate the nature of the partnership between local agencies and the doorbell-surveillance company. In one of those documents, Angela Kang, who manages public agency partnerships for Ring, wrote in an email to SCPD that “all press release materials will need to be approved by our Ring PR team prior to publishing, so please submit all your drafts to

me***@ri**.com

.”

Kang sent SCPD four attachments of press release materials, including a “Press Release Template,” “Sample Social Media Posts,” “Talking Points and Reactive Q&A Sheet” and “Neighbors App Logo and Imagery.”

When this news organization asked Santa Clara police to include those attachments, they denied the request without offering any justification. According to Dave Snyder, executive director of the San Rafael-based free-speech non-profit First Amendment Coalition, that’s a clear violation of the California Public Records Act (CPRA), which requires the government to disclose public records upon request and cite specific exemptions to the law in order to deny requests for information. A Santa Clara County Civil Grand Jury slammed the city for the same offense earlier this summer.

As of press time, the city of Santa Clara had yet to respond to requests for what CPRA exemption justified its withholding of those Ring-related attachments.

Per the terms of their contracts with Ring, police in San Jose and Santa Clara cannot disclose the terms of their video surveillance program with the company. But San Jose’s agreement with Ring, at least, includes a provision for requests made under the CPRA. To wit: “All records provided to the city by Ring, and any records used by city pursuant to this memorandum of understanding (MOU) will be subject to disclosure as required by the California Public Records Act and the city Open Government Ordinance.”

Santa Clara’s MOU with Ring omits that CPRA clause. According to Snyder, that’s a problem. “It gives broad discretion to Ring to designate records as confidential,” he explains. “It appears to give a private entity the final say about what’s public and what’s not. That’s improper. The Public Records Act makes clear that a government agency has an independent obligation to provide records and cannot put the public rights of access in the hands of a private company.”

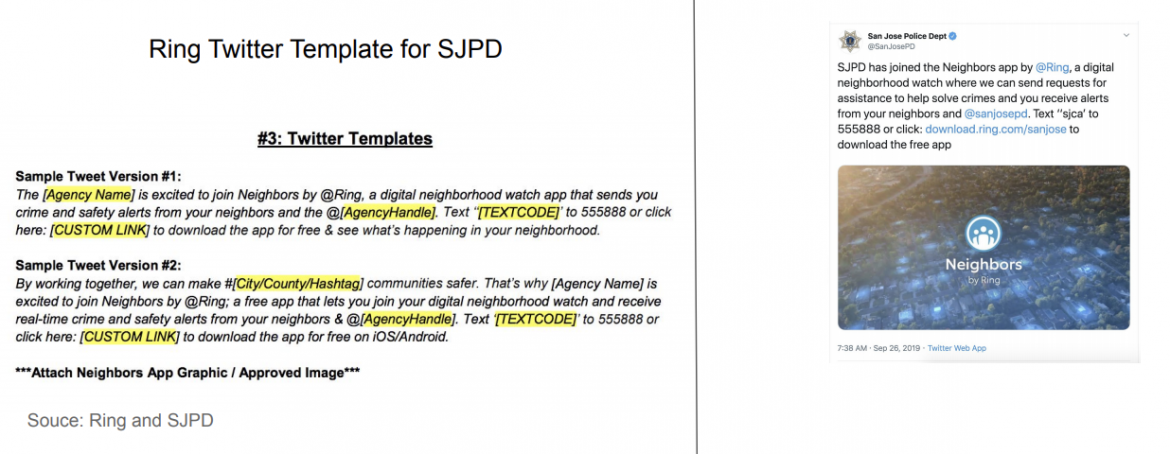

San Jose police proved more forthcoming than their counterparts in Santa Clara. Records obtained from SJPD show that Ring sent the department talking points and fill-in-the-blank templates for its social media announcements on Facebook, Nextdoor and Twitter.

And according to a review of the messaging, SJPD’s social media posts have largely mirrored Ring’s templates.

For example, Ring’s suggested tweet for SJPD reads: “The [Agency Name] is excited to join Neighbors by @Ring, a digital neighborhood watch app that sends you crime and safety alerts from your neighbors and the @[AgencyHandle]. Text ‘‘[TEXTCODE]’ to 555888 or click here: [CUSTOM LINK] to download the app for free & see what’s happening in your neighborhood.”

The San Jose Police tweet reads: “SJPD has joined the Neighbors app by @Ring, a digital neighborhood watch where we can send requests for assistance to help solve crimes and you receive alerts from your neighbors and @sanjosepd. Text ‘sjca’ to 555888 or click: http://download.ring.com/sanjose to download the free app.”

A Ring representative, who asked to be identified only as a spokesperson for the company, wrote in an email that “Ring requests to look at press releases and any messaging prior to distribution to ensure our company and our products and services are accurately represented.” The Ring official wrote that police departments can use Ring’s social media templates at their discretion.

Meanwhile, Ring sent Santa Clara PD the “Neighbors Portal Training Guide” with instructions for the agency to comment and post on the Neighbors app. SCPD has a heat map of all active Ring cameras, though Ring’s training guide says the camera locations are “obscured for privacy.” When police issue a request for video recordings, Ring sends out an alert on behalf of the police department to users in the vicinity of the crime, requesting video recordings with a personal message from a police officer.

Ring emailed SCPD crime analyst Suzanne Silva a demo alert saying, “Ring is assisting Crime Analyst Suzanne Silva of the Santa Clara Police Department in requesting videos that may help with an investigation of an incident that occurred near your home.”

Along with Ring’s statement is a message from Silva. “I’m reaching out in hopes of obtaining footage that may assist in our investigation of an incident that occurred in this neighborhood,” she wrote.

The alert ends with: “Stay safe, Ring Team.”

Ringing Off

Andrew Ferguson, author of The Rise of Big Data Policing, says everyone should be skeptical of Ring’s reach.

“We should pause when a private company is demanding editorial oversight of public press releases about public safety,” Ferguson says. “That is an unusual move and seems to infringe on the question of who the city is working for and with.”

For his part, Garcia insists that he has the final stamp of approval when it comes to SJPD messaging. If Ring disagrees with his press releases and ultimately wishes to end its partnership, then so be it—he says he’ll severe ties with the company.

“I'm not going to have anybody blemish our brand,” Garcia says. “I know Ring wanted to have some say in [the press releases]. But nothing would get released if I didn’t approve it. If one day, they disagree with a press release I’m putting out and want to break the contract, then the partnership’s over. We’re partners, but ultimately, the last say will not be theirs. We cannot allow a private company to dictate how [the] police department messages to the community.”

Another point of concern for privacy advocates is the lack of public oversight inherent in these kinds of contracts. “People in town have no say about the existence of the partnership,” Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) policy analyst Matthew Guariglia says. “It’s not being discussed in city council.”

That’s why the ACLU lobbied lawmakers to adopt its Community Control Over Police Surveillance (CCOPS) legislation in 2016, according to Snow—so elected leaders could evaluate police departments’ surveillance policies.

That was the same year Santa Clara County adopted its Surveillance Technology and Community Safety Ordinance, which requires the Board of Supervisors to analyze and approve spy-tech policies of county departments. Cities including Palo Alto, San Francisco and Oakland have enacted similar local laws.

The cities of Santa Clara and San Jose have not.

Garcia acknowledges that San Jose city council members didn’t weigh in on SJPD’s partnership with Ring, a Santa Monica company acquired last year by Amazon for $1 billion. The chief, however, believes that a city surveillance ordinance is unnecessary. “The last thing we want in San Jose, especially with a lean department, is to frustrate our efforts even further,” Garcia says. “We’re just trying to keep our city safe and use the tools at our disposal.”

With Ring’s all-seeing eyes in the mix, he says the public is better off.

“When I was a homicide detective, I would go out and knock on doors, asking people for surveillance footage,” Garcia says. “This partnership with Ring will make the process more expeditious, and we will be able to put serious criminals off of our streets quicker. We want to leverage technology to help us keep our community safe.”

Ring has become San Jose's new neighborhood watch.

Public & Private

Critics worried about Ring aiding and abetting Big Brother are overreacting, California Police Chief Association President Ronald Lawrence says.

After all, this app simply expedites surveillance video requests for police departments. “ACLU and their advocacy groups tend to spin this,” he argues. “Police agencies have no desire to be in the 24/7 surveillance arena. Furthermore, we don’t even have the resources. There’s no infrastructure.”

To those concerned about corporate overreach, Lawrence says that private companies have long done business with police departments. For example, Axon, the manufacturer of the Taser, is also one of the largest vendors of police body cameras; gun manufacturers Sig Sauer and Glock are major suppliers of firearms; telecom giant Motorola owns a large share of the radio infrastructure for police and fire departments across the nation.

As technology has evolved rapidly over the last decade, Lawrence says it’s prudent for police departments to partner with technology companies to upgrade their tools. The Neighborhood App is just the latest example in a long line of public and private policing partnerships.

Civil liberties groups have a history of thwarting the efforts of law enforcement to adopt modern technology, Lawrence continues, and Police Chief Association leaders are getting worried. Ring isn’t their first target, he notes. Civil liberties advocates successfully backed a bill to temporarily ban facial recognition in police body cams.

“We faced the same [problem] when Tasers first emerged. People said, ‘Oh my god, you can’t have that.’ Well the reality is, the use of police baton—a far more blunt instrument—decreased significantly,” Lawrence says. “We need to embrace technology.”

New Normal

Privacy advocates say these kinds of privately penned, publicly adopted policies are becoming the new status quo. As Ring continues to expand its partnerships, Ferguson warns that Amazon is gaining unfettered access to people’s daily lives.

All over the world, consumers have voluntarily adopted smart speakers with always-on microphones—like the Amazon Echo and Google Home. (Google also owns the wifi camera and smart thermostat maker Nest.) Our phones, watches and even our appliances are increasingly collecting information from sensors and beaming it to the cloud, where the data is stored and can potentially be correlated with personal profiles.

“Amazon is selling surveillance as a service,” Ferguson says. “They are building more and more information about all of us. We are normalizing ordinary surveillance, building networks of surveillance in certain neighborhoods that will have a chilling effect for people going about their business.”

For many San Jose residents, surveillance technology’s potentially chilling effect on crime overshadows concerns about personal privacy and government transparency. Vehicle break-ins, porch pirates and burglaries are on the rise. Robberies in San Jose spiked over 15 percent from 2017 to 2018. And violent crimes jumped more than 7 percent from 2018 to this year.

“Anyone that is against using cameras to deter crime and convict criminals has to reassess their values,” SAFER San Jose President Issa Ajlouny says. “People are sick and tired of the crime that’s going on on a daily basis.”

Case in point? Residents of a neighborhood in South San Jose recently voted to allocate almost $600,000 to install 300 surveillance cameras, and 900 San Jose residents have also signed up for SJPD’s camera registry program, where residents and business owners register the locations of their surveillance cameras. Councilwoman Pam Foley also launched camera rebates, where residents can receive up to $100 for installing surveillance cameras; in return, they must register with the camera registry program.

Garcia says SJPD’s Ring app will be more effective than the camera registry program. “We know where the cameras are, but detectives still have to physically go out to those neighborhoods to knock on doors, get the videos, ask the residents if they can have the videos,” Garcia says. “With the Ring app, they can do it remotely from the office.”

Privacy advocates say the risks of surveillance overreach are too great to proceed with anything less than extreme caution. Lawmakers in San Jose, however, shrugged them off. Privacy advocates lobbied for a surveillance ordinance in 2014 after learning that SJPD quietly purchased a drone without any policy in place restricting its use—to no avail.

A year later, Mayor Sam Liccardo and councilmen Johnny Khamis and Raul Peralez sought to place electronic readers on garbage trucks to scan license plates of cars parked on city streets. Derided as “Big Brother” and “Orwellian,” the 2015 proposal was consigned to the trash heap of failed ideas almost as quickly as it was floated.

“We met with San Jose council members,” Council on American-Islamic Relations consultant Sameena Usman says. “But there really wasn’t much movement. If we had a strong surveillance ordinance, we wouldn’t have had the drone or Ring problem. We need to have the public weigh in on such important decisions.”

At least San Jose seems to be moving in the right direction.

Earlier this fall, the City Council passed a set of “privacy principles” to guide San Jose’s data management. “Before we draft the laws and regulations, we need a constitution,” Liccardo said. “That’s what we got. We’ve got a good start, but this is only the first step.”

Too funny! Maybe watch the movie scene from the Big Lebowski where the “Dude” is notified when his stolen car is found and towed to a police yard. He asks if they are investigating and the police officer replies “Yeah We have a team of 12 detectives working on the case” d chuckles afterward.

“Security video helped authorities track down Joey Vicencio, the 21-year-old Santa Claran charged with attempted murder after 10 rounds from a semi-automatic rifle were fired into the Martin Luther King Jr. Library last month. Citizens’ footage also provided clues that led to the identification and arrest of Carlos Arevalo-Carranza, the 24-year-old accused of murdering San Jose resident Bambi Larson earlier this year.”

It seems rather disingenuous on the part of the author to, on the one hand, state that Joey Vicnecio is a ‘Satna Claran’ while, on the other hand, failing to state that Carlos Arevalo-Carranza was a diagnosed psychotic with multiple felony convictions and a Salvadoran National and illegal immigrant and that his deportation hold requests were denied on at least nine separate occasions by Santa Clara County.

I understand that this isn’t the main thrust of the article, but don’t you think that an adherence to journalistic integrity (not the oxymoron most people suspect this term to be nowadays) would demand that these facts be mentioned?

After all, it’s very easy to say that easier access for law enforcement to services like Ring might have sped the identification and apprehension of these suspects. But, it’s no less fair and accurate to say that, had Santa Clara County acquiesced to any one of those nine aforementioned detainer requests, Bambi Larson would, arguably, not have been murdered by said, undermentioned psychotic, violent, criminal illegal immigrant.

> Citizens’ footage also provided clues that led to the identification and arrest of Carlos Arevalo-Carranza, the 24-year-old accused of murdering San Jose resident Bambi Larson earlier this year.”

It is simply outrageous that the only information that the community seems to be able to get on the tragic death of Bambi Larson is anonymous leaks on social media forums.

The south San Jose community was REALLY REALLY outraged by the event, and things were made many times worse by the OBVIOUS, POLITICALLY CORRECT response by local officials to defuse public response by suppressing all information on the details of the crime, the criminal history of the perp, and the clear contributory effect of bone headed progressive policies like sanctuary cities and non-cooperation with ICE.

People are still steaming and California politicians are going to find out how steamed they are in 2020. Starting with Gavin Newsom, and including a few especially loathsome members of Congress.

Mt Bubble,

Wouldn’t it be ironic if the way to progress in California would be to get rid of the progressives !

Well said Officeranonymous.

“I understand that this isn’t the main thrust of the article”

> “I understand that this isn’t the main thrust of the article”

The main thrust of the article wasn’t very interesting. I blame Richard Chan for fostering boredom and apathy.

All credit to OFFICERANONYMOUS for extracting a nugget of thrust from an otherwise thrustless article.

The Council on American Islamic Relations lies.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3NqVlP_7UjE