Deputy Robert Aviles, armed with a clipboard and brightly colored paperwork, approaches the porch where a straw welcome mat bears the black-lettered inscription, “Don’t even think about it.” His partner, Kevlar-clad Deputy Paul Woehl, hangs back several feet as Aviles raps on the white door to deliver the bad news.

“Sheriff’s Office,” he announces.

A disheveled middle-aged woman answers and, after a brief exchange, beckons the officers inside. They follow her to the musty hallway, where another tenant appears from the back. The floors are strewn with clutter—hypodermic needles, heaps of junk mail, rumpled-up blankets. Translucent orange pill bottles sit atop end tables and an old player piano. Christian religious art adorns the walls.

“As of right now, as you know, the eviction is scheduled for the 25th,” Aviles breaks it to them. “That’s probably going to be the for-sure day. So make sure you stay in touch with your social workers. Has anyone moved out?”

Another tenant chimes in, telling deputies that they expect to move into a new place called “the purple house.” Aviles nods and takes notes.

“I need you to stay in touch with your social workers,” he repeats, trying to calmly convey the urgency of the predicament. “Can you do that? Because you have until the 25th, remember, and that probably won’t get extended again. OK?”

“Oh” the housemate replies, “is that right?”

“Yeah, that’s usually that’s the max number of days that they give,” Aviles says.

“What do you mean to say?” she asks, anxiety creeping up in her voice as she wrings her hands. “It won’t be extended anymore?”

“It probably will not be extended,” Aviles tells her apologetically. “Do you have any questions for me?”

“How about if we don’t have a place to go?” she wonders. “Where will we go?”

“That’s what we’re working on,” Aviles reassures her. “I don’t know all the alternatives, so I have some people looking into that. They may come and talk to you also. But hopefully we’ll get something figured out.”

Aviles says he bought as much time as he could for the women left in the single-story flophouse, which the landlord subdivided to accommodate several mentally ill tenants. Serving the eviction as scheduled a month prior would almost certainly have left the some of the home’s occupants on the streets.

“Last time we were here, a few didn’t even know that the landlord wanted them out,” Aviles tells me as we walk away from the tan stucco home on a quiet street in San Jose’s East Side. “We put up the notice, but I think somebody tore it down. If we went through with business as usual that day, the landlord would have been there with the locksmith, forced them out and that would be it”

Not anymore. Not if he can help it.

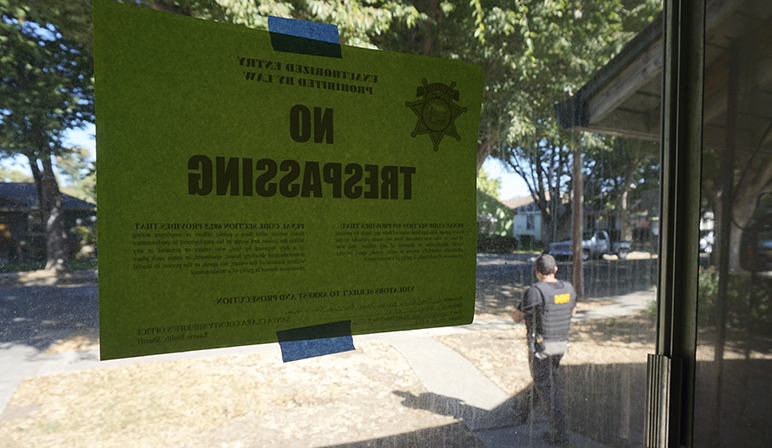

Inside a boarding house for mentally ill tenants a month before their eviction. (Photo by Jennifer Wadsworth)

Seven years serving eviction notices for the Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Office haven’t made it any easier for Aviles to tell someone they have to leave. Especially for the single parents, the children, the mentally ill and countless others who could have been helped at some earlier point in the series of events that pushed them to the brink. Knowing that too many evictions could have been prevented or at least alleviated inspired him to create what he calls the Displacement Mitigation Team.

“This is a way to catch people who are not able to advocate for themselves,” says, a 15-year Sheriff’s Office veteran who expects to get reassigned to patrol in 2017.

Aviles began to assemble the task force earlier this year and formally deployed it for the first time in September. The idea stems from a counterpart in San Francisco, where deputies enforcing evictions link vulnerable tenants to social services instead of casting them out on the streets. He pitched the idea to his boss at the time, Lt. William Middleton, and Sheriff Laurie Smith, who told him to run with it.

“The concept is simple,” says Middleton, who recently stepped down from leading the civil services unit. “But it really does go above and beyond.”

Under California law, only sheriff’s agencies can enforce civil procedures. That includes evictions, which begin in court as lawsuits called unlawful detainers. A judge weighs the evidence to determine whether a tenant has violated a contract with the landlord. If so, they issue a writ that a sheriff’s deputy is mandated to post within three days and enforce less than a week later.

“By the time we get there, the case has been adjudicated,” Aviles says. “What we have is a five-day window between the time we post it and the time we evict.”

That leeway between notice and enforcement could alter the course of a person’s life, he says. That’s when the displacement team gets to work. By taking advantage of that narrow timeframe, Aviles hopes to prevent situations like so many he encountered in the past. He recalls an assignment in 2010 when he had to evict a mentally ill woman who was the sole caretaker of her brain-damaged daughter. Evicting them—a week before Thanksgiving, no less—would have rendered the women homeless.

“We told the landlord we just couldn’t’ do it,” he says, adding that his sergeant at the time helped him push back. “No way we’re putting them on the street.”

Instead, he called the county’s Office of the Public Guardian and Adult Protective Services, which informed him that it would take weeks to relocate the two women through that route. While scrambling for a way to avoid eviction, he did some detective work and tried to piece together their story. It took an hour of coaxing before the mother would admit that it was her name on the paperwork, let alone open up to Aviles. By prying her for information, he found out that the mother, who suffered from paranoia, apparently forgot to renew an authorization to receive her daughter’s public assistance stipend. That, he presumes, is how she fell behind on rent.

“There were so many chances along the way to prevent this,” says Aviles, who went through crisis intervention training in 2010, which opened his eyes to the plight of the mentally ill. “Over the years, cases like that have been on the forefront of my mind. There should be a process that guarantees the best solution to these horrible situations.”

With Sheriff Smith’s blessing, Aviles went around meeting with various nonprofits, social service agencies and county officials to create a network.

“It was months of me literally walking through the doors and saying, ‘So I have this idea,’” he says. “There was a lot of beating my feet on the pavement and pitching this to various people who passed the word onto various other people.”

In the course of laying the groundwork for the displacement mitigation team, Aviles enlisted social workers and attorneys. He got United Way to sign on, prompting the nonprofit to extend its 2-1-1 social services help line and algorithmic needs assessment to the effort. He put together a punch list with instructions for clerks and deputies to identify people who need the extra help.

“At the county, we really want to support that kind of effort,” says Steve Preminger, a special assistant to County Executive Jeff Smith. “We need to protect people’s dignity, to make sure that they don’t decay.”

Middleton compared the approach to the way police agencies respond to human trafficking cases, where social workers and advocates agree to ride along.

“We’re simply extending that to the way we deal with evictions,” he says.

In a broader sense, the strategy reflects the changing nature of law enforcement. Decades of dismantling public psychiatric hospitals, supportive welfare programs and other institutions that once cared for people in need has turned the modern police officer into one of the few tax-funded agents of public wellness.

It’s a reality that all too often plays into disaster. More than half the people who die at the hands of police had some kind of disability, according to a 2016 report by the Ruderman Family Foundation. The study’s authors, historian David Perry and disability expert Lawrence Carter-Long, looked at incidents from 2013 to 2015. Their conclusion: that people with psychiatric disabilities are presumed dangerous in police interactions.

“Police have become the default responders to mental health calls,” the report found.

New York City police officer turned psychiatrist George Patterson says most of modern policing involves services related to social work. In his view, latter-day cops are trained as soldiers but deployed as caretakers.

“The demand for services in general has grown and shifted,” Preminger agrees. “It speaks to income inequality, job training, population growth and budget cutbacks. These are the issues we’re discussing at the county. We’re talking more and more about how to adapt to this changing role—not just for police, but for all of us in all our departments.”

This past month, the displacement mitigation team got its first call from a tenant. Normally, they come from landlords or family. The tenant, who was being ousted by an out-of-town investment group, saw the five-day eviction notice taped to the door and called Aviles, unleashing an uninterrupted stream-of-consciousness diatribe.

“The overriding theme was that the sheriff has no authority to evict because various senators and FBI personnel have protected her from foreclosure,” Aviles recounts.

Though clean and well furnished, the woman’s home was equipped with about two-dozen security cameras and at least three monitored alarm services. Sensing she needed extra support, Aviles asked the landlord for more time. Through traditional investigative methods, he tracked down her ex-husband, who passed his phone number to relatives in India. It took the mitigation team more complicated maneuvering through another ex-husband up in Seattle and a friend in Los Angeles, but the woman eventually reunited with her family abroad.

“She is now in India with her father and getting professional help,” Aviles reports. “I spent a lot of time trying to find somebody who knew about her. I talked to the neighbors, who really liked her and wanted to help. It’s actually a testament to what a good soul she is. It shows how mental illness creates this shell that gets thicker, and thicker, and thicker as you deteriorate, but inside there’s somebody that still loves.”

Of the 15,400 evictions processed in this county since 2006, only about 5 percent involve the kind of cases the mitigation team is designed to help. Aviles expects to deploy the above-and-beyond interventions about twice a week. Since launching the team this past fall, he says he’s helped six people avoid homelessness or traumatic displacement.

“There’s a whole universe of problems related to the housing crisis,” he says. “But here’s a specific chance, a way to target our efforts to prevent homelessness before it starts. And to protect people who may not be able to fend for themselves.”

By connecting with various agencies, the displacement team could also reverse engineer the crises that brought people to the point of eviction.

“There are all these points along the way where someone or something may have helped them,” Preminger says. “Now that we’re looking at it this way, we can start filling those gaps in service.”

Only a fraction of evictions in this county qualify for extra help from the Displacement Mitigation Unit. (Photo by Jennifer Wadsworth)

Many years ago I rented aparments (all since sold). The few evictions I did all came down to one thing: the tenant’s failure/refusal to pay the rent.

Once a tenant makes the decision to not pay their rent, their thinking is shifted onto a completely different track. Suddenly the money they set aside for rent is available for whatever they want, and it’s promptly spent. That’s the pattern, and I’ve never seen an exception to it.

On the other hand, when renting an apartment I always explained the situation, and I told them that if they anticipated a problem paying the rent they should contact me right away so we could work something out. In the very few cases a tenant called before the rent was due and told me they were short of money, I always worked it out with them. Those folks never faced an eviction.

But those were very much the exception. For the most part, when a tenant made a conscious decision to not pay the rent, they never had anything to put toward the rent due. It was always all or nothing. Furthermore, I never found out about it until the rent was overdue.

Question: Is it fair to all the other tenants who pay as agreed, to cancel an eviction for the one who decides not to pay? Because contrary to what’s implied in the article, every tenant understands that the rent is due every month.

I agree that guiding people to the appropriate social services help is a good thing, especially in the extreme and exceptional cases reported in this article. However, those comprise a very small fraction of evictions; maybe 5% at most. But this article gives false hope to the other 95%, almost all of whom are evicted because they decided to stop paying their rent.

Ask yourself: what if your employer decided he couldn’t pay you this month? Should the Sheriff come and tell you that your employer has problems, and so would you mind waiting weeks or months to get paid?

This Sheriff is simply a scofflaw. Who elected him to overrule a judge’s order?

The Sheriff is walking on mighty thin ice here, in my opinion. Because if a judge issued an order that was subsequently countermanded by this Sheriff, sooner or later a rental property owner will go back to that same judge, and tell him/her that someone ‘more important’ has decided that he “just couldn’t” obey the judge’s order. In that case…

…pass the popcorn! ☺☺☺

Your caring and empathy are heartwarming at the approach of Christmas.

LJW,

Thank you! It’s always a pleasure to be preached to by the holier-than-thou contingent.

“The demand for services in general has grown and shifted,” Preminger agrees. “It speaks to income inequality, job training, population growth and budget cutbacks.”

Attributing an increasing demand for services to “income inequality” implies that need is caused by the disproportionate accumulation of wealth at the top, a theory which, if Mr. Preminger actually believes, should be cause enough for him and the county he works for to use the power of government to demand redress from the local high-tech wealthy (with at least as much enthusiasm as the Democratic Party has when reaching out to those rich folks for contributions). But given that nothing like this has ever happened, I guess we can strike up the income inequality charge to the class-warfare tactics traditionally favored by socialists and communists.

Before we question what role, if any, job training has in creating economic need, we should at least confirm that there exists a resident population that has been denied it. Are there local school systems that do not, free of charge, accommodate students interested in learning a trade or preparing themselves for jobs in industry? I think not, so it seems that the population about which Mr. Preminger speaks have not been denied job training, they just failed to take advantage of it when offered, and now their ineptitude is being used to indict society at large. The fact of the matter is that the job training mantra so popular with liberals is job training for a class of people who, due to low intelligence, laziness, or personal choice, have a track record of failing to take advantage of opportunities offered, thus making them poor bets to do better the second or third or fourth time, and making job training programs a very poor investment of taxpayer funds.

Am I reading right, has a local government official really linked the growing demand for services to population growth, in a county that has steadfastly denied that the illegal immigrant community, despite its massive numbers, represents a drain on social services? Could it be the residents he pegs as responsible for the drain are the newly-arrived programmers and engineers? Not likely, which leaves only the homeless, but that is a population the county would like to portray as homegrown, lest anyone get the idea that the government’s generosity (in services and tolerance) is actually drawing the needy from elsewhere.

And thus we are left with budget cuts, an excuse that would seem a contradiction in a county experiencing significant growth and home to the greatest wealth-producing industry in the world. Given that a county’s population represents people paying taxes to that county, and the presence of a great industry increases salaries (and sales taxes), raises property values (and taxes), and employs a workforce requiring very little in the way of county services, it would seem that the county’s budget cuts, if not the work of misplaced priorities, are largely due to this county’s political position in regards to illegal aliens and the homeless. In other words, these morons have invited so many of the wrong people here that they’re breaking the bleeding heart bank. Big surprise.

> “It speaks to income inequality,

Perfect “income equality” occurs ONLY at “absolute zero”, the state where no one has any income.

> job training,

The progressive idea of “job training” is worthless: paying somebody to speechify something or other to unmotivated, disinterested superannuated “children” fiddling with their smartphones. “I’m really into art. I could never work for a corporation or anyone who’s against the environment.”

> population growth

Build a wall at the border. Cut off the source of “anchor babies”. That will reduce “population growth”.

> and budget cutbacks.”

Reduce population. Reduce budgets.

This is AWESOME! If people in this valley were not so greedy, the place would be so much better, people would be happier, and everything just better.

Hope this spreads everywhere!!!

> Hope this spreads everywhere!!!

SAM: You’re a GENIUS! Do you think this would work in Mexico?

If the Mexican government would just prohibit evictions of Mexicans in Mexico, and tell Mexican landlords to stop being greedy, it would end the problem of illegal immigrants.

Mexico would be better, people would be happier, and Mexicans would WANT to stay in Mexico!

The local Democrat brain trust has embraced Ronald Reagan’s supply side economics as the solution to the “housing crisis”.

How many times will we be told by government authorities and housing “experts” that “the problem is that there just isn’t enough inventory”. They advocate for changing and eliminating rules imposing any restraint on building housing- more and more and more housing. As if this “crisis” can be solved by addressing only the “supply” side of the supply/demand equation.

The truth is the supply of housing will never keep up with the demand here in the bay area as long as there is no limit on immigration. We need to allow immigration but we need to meter it at a sustainable rate. (Imagine. Democrats copying Reagan and me talking about sustainability!) That means not only controlling our southern border but it also means pissing off our high tech masters by telling them no you can’t have all the H1B visas you want. Housing will become affordable when we exercise our sovereign right to limit immigration thus limiting demand.

Twenty year waiting list , no govt section eight monies, those with the vouchers stay for generations, therefore new people are not eligible for section eight housing.

A heartwarming tale perfect for the holidays. Kudos to Sheriff Avile and his department having their heart in the right place. Distinguishing the mentally challenged and their inability to do their paperwork in a timely fashion to prevent their eviction from the general evictions that I am sure they are enforcing on the kind that Smokey is referring to, is clear. What this article says is that those in the frontline have their work cut out for them and if they put their heart and minds together, they come up with appropriate procedures and policies that can make our systems become more humane. I sincerely hope, we as citizens can also move from our “emotions” and “judgement calls” and proceed with identifying solutions that are objective and applicable rather than shooting down good procedures with our opinions.

M.S.,

No one has said a single positive thing about the people who provide shelter for (in my case) dozens of families. You didn’t, either. Maybe you folks think I’m related to Donad Trump, or something. Could that be it?

My suggestion: walk in my shoes for a few years; answer a phone call at 11:00 at night from a tenant complaining that the toilet won’t stop running. Or get complaints that another tenant took someone’s parking place for a couple hours.

Or go over to find out why the rent wasn’t paid and no one answers the phone — and find a demolished apartment in need of new paint, new carpets, repairs to the holes in the sheetrock and the broken windows, cracked doors, etc., and realize that the rent wasn’t paid for a very good reason: the tenants had skipped town a week before.

Or find out that a tenant’s hippy friend had moved in for a week, and brought along his own personal supply of of cockroaches — critters that like to travel along electric lines, thru wall outlets, and along drain pipes between apartments like they’re on the roach light rail, and requiring an expensive fumigation all the units. Then listen sympathetically when the other tenants call to complain about the inconvenience. The fun never ends when you have rental property.

Whenever someone filled out an application to rent an apartment, they wanted it more than any others they had looked at. Whether it was the reasonable rent, or the location, or whatever, it was the one they wanted to call home. And about 99.8% of them were fine folks who kept their end of the deal. They were happy with where they lived, and I was happy to have them as partners in our mutual cause.

I provided families a warm, safe place to live, and I never forced anyone to move there, not once. They wanted to rent the apartment. (I also took in Section 8 tenants, welfare cases, etc., and none of them were ever a problem.) I provided everyone a nice, safe place to live, with no deferred maintenance. And whenever someone had a complaint or a request, I did my best to resolve it.

Except according to some commenters here, I’ve got no empathy. I’m greedy, and my comments are simply emotional judgement calls. Those commenters are happy to take their pot shots from the peanut gallery, because that’s how the Media has trained them to think — to demonize “landlords” — and they’re head-nodding right along with the media’s narrative.

But I’ll bet that not one of the critics here has ever been in the rental property business.

Try it some time, folks. Walk a mile in my moccasins. I suspect you’ll be singing a different tune.

II agree with Smokey’s perspective.

People who disparage that landlord are the same people that if their employer did not pay them for their labor would be screaming that it is illegal to work for free. As a poor person myself, I once rented an apartment, and when I could not pay, I quickly accepted that it was my problem, not the landlord’s problem and amicably moved-out.

Later when my luck improved, I purchased a two family home with the goal of giving my family a nice place to live and to just get by. Shortly after I purchased my home, I rented the second apartment to a tenant who “needed a break, someone to give me a chance”. Two months later, the family with three adult children stopped paying rent. Then appeared the eviction lawyer’s expense and court fees that I could hardly ever afford. At the end, the Tenant, her three adult children and their girlfriends/boyfriends stayed living rent free while I barely was able to pay my mortgage, water bill, gas, and heat. Three times, a social service agency called to request that I lower the rent. On one of those days that a case manager went on and on how we have to help those in need, my own daughter had to borrow money for lunch because I had no money that day. The family money had gone to pay a water bill that had tripled when the adult children moved in their boyfriends/girlfriends. The cost of covering utility bills for all the tenant overwhelmed my small paycheck.

This is the harsh reality that government agency refuses to acknowledge not because they care, but because they want to keep shelter beds down and oblige landlords to shelter non-paying tenants for free. Since then, I have kept that apartment empty. I am happier, broke, but not placed in the situation where I can lose my home for a tenant with three adult children who do not seemed to make a strong effort to pay rent and feel so entitled to live for free. Before they left, they trashed the apartment and on one wall wrote, “Greedy landlord”. On the day of the eviction, while I held on to a shut off notice from the electricity company, the tenant asked me why I was doing this to her? Yes, having shelter is a human right. Having clothes to protect you from the cold is also a human right, but just like we cannot just walk out of a store without paying for the clothes that we need, no one should be expected to live rent free. The consequences to the landlord is costly and if government wants small landlords to assist in helping tenants with poor credit that normally cannot obtain an apartment from larger apartment buildings, then they also have to make sure that the housing court process is fair for everyone. Having a non-paying tenant in Housing Court for over a year is not going to buy any consideration for those deserving tenants that deserve a break. Everyone deserves a chance, I agree. But never should it be at the expensive of another human being, even if that person happens to be a landlord.

This is my experience.

I am starting to have a similar experience where my tenants cannot afford another place to live and I know the judge is going to make me cut them a break even though they have been paying way under market value for 3 years. What’s going to happen when I go into foreclosure? I guess I’ll have to move out and they will stay squatting.