The software is remarkable. Transformative, even.

Combing through hundreds of millions of records from Santa Clara County’s criminal justice system, hospitals, shelters and charities, it draws connections that human analysts might miss. The data-mining service developed by Palantir Technologies identifies people who cycle in and out of jails and emergency rooms the most, which allows service providers to prioritize who to help first—potentially saving lives.

Since launching the program called Project Welcome Home in 2015, the county and its nonprofit partners have housed 111 chronically unsheltered people with this approach. On the streets, each of those clients cost the public $62,473 a year in emergency services, according to the county; with a roof over their heads, that figure dropped to $19,767.

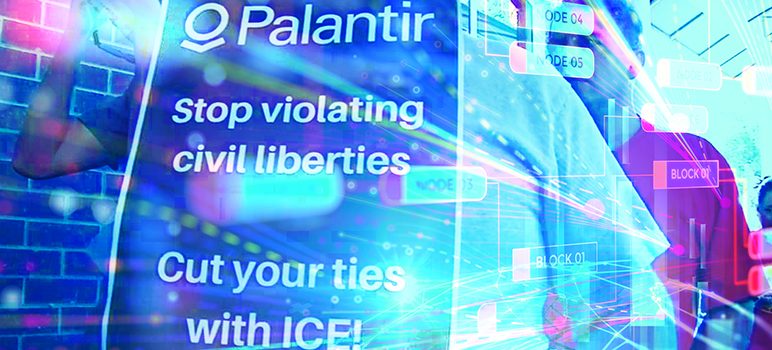

But the project’s association with Palantir has recently come under scrutiny by privacy advocates who are increasingly wary of Silicon Valley’s role in the U.S. security establishment—particularly Palantir’s ties to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

“Given my work and knowing the company’s role in law enforcement and surveillance, I can say they’re a bit of a creepy choice,” says Mike Katz-Lacabe, who founded the Center for Human Rights and Privacy.

Dozens of protesters who gathered outside Palantir’s Palo Alto headquarters last month voiced a similar sentiment, singling out the company’s $53 million “mission critical” contract with ICE, which dates back to the Obama administration but gained widespread attention under President Trump. They presented a letter to CEO Alex Karp demanding that he stop aiding federal efforts to deport millions of immigrants. The July 31 demonstration was part of a nationwide day of action—amplified on social media under the #WeWontBeComplicit hashtag—against businesses, schools and government entities linked to Trump’s deportation machine.

The county’s contract with the tech firm co-founded by billionaire libertarian Peter Thiel slipped below the radar of last month’s rallies. Perhaps that’s because the county’s work with Palantir has an altruistic aim and outcome—unlike the military and policing contracts for which the company is better known.

Or because of the demographic it targets.

“The fact that it’s happening to people who often don’t have a voice, people in desperate situations and amassing a whole bunch of data only on them could explain why this hasn’t gotten as much scrutiny,” Katz-Lacabe said.

After reading through the county’s 31-page agreement with Palantir, he added: “Combining health and criminal data on individuals seems Orwellian to me. ... This wouldn’t be acceptable to any other group of individuals.”

Since the county entered into its deal with Palantir a year before the Board of Supervisors adopted a policy governing spyware and surveillance technology, Katz-Lacabe said it’s worth revisiting the matter with public discussion.

Especially, he added, since California has positioned itself as part of the resistance against Trump, suing the administration to oppose arguably discriminatory, anti-immigrant policies. Also because the county considers itself a sanctuary jurisdiction, which basically means that, although it still contracts with ICE, it prevents immigration authorities from interviewing inmates without a judicial warrant.

“In light of that,” Katz-Lacabe said in an interview this week, “they have an extraordinary obligation to be very transparent.”

After teaming up with the county for Project Welcome Home, a six-year rapid re-housing effort led by the nonprofit Abode Services, Palantir helped launch a second initiative called Partners in Wellness, which provides mental health services to about 250 people with severe psychiatric disorders. Part of the interest in tracking the efficacy of the two initiatives goes back to the funding model itself, a public-private approach to charity that uses an “outcomes-based” model to determine success.

Also called “pay for success,” the financing deal starts with an up-front investment from the private sector—in this case $6.9 million from for-profit and philanthropic backers including Google and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. A designated adviser (Third Sector Capital Partners) keeps the project on track while an independent evaluator (the University of California, San Francisco) studies its impacts. The government only foots the bill if and when the project produces measurable results.

Palantir initially offered its software to the county on a pro bono basis—part of a broader effort by the company to link arms with public service, charitable and global aid organizations—and has since become a paid contractor, albeit one that offers bargain-basement prices. The county’s Behavioral Health Department struck up a $400,000 deal with the data firm and the Affordable Housing Office a $250,000 agreement—both of which sunset in 2022. Other technology companies use a similar approach to get their foot in the door. Axon, for example, offered free body cameras to police departments throughout the U.S. and then later charged them to store data.

Lead Deputy County Counsel Greta Hansen stresses that the agreements with Palantir include strict privacy protections to prevent sharing data with outside entities. They also authorizes the county to conduct compliance audits—although officials could not immediately answer how many of those reviews have been done.

Further, Hansen said Palantir obtains only as much information as it needs to do its job, that each client must consent to having their information collected and that citizenship status of the clients served isn’t a factor.

“County policy has been really crystal clear since 2010 that county services aren’t conditioned on immigration status,” she said. “We serve all folks and the county is prohibited from sharing anything with ICE.”

Abode Executive Director Louis Chicoine echoed Hansen’s assurance, noting that the people served by the initiative tend to be legal residents anyway. “Chronic homeless target populations are generally not coming from a new immigrant population, but rather more often long-term local residents of the county,” he said.

Eunice Hernandez, an organizer for Sacred Heart Community Services who works with a cross-section of clients that include the undocumented and un-housed, said she feels uneasy about that kind of generalization.

While it may be generally true that homeless people in the South Bay have been longtime residents, Hernandez has firsthand experience working with people who are both undocumented and unsheltered. It’s also worth noting that many of the county’s 200,000-or-so undocumented immigrants are long-term—sometimes almost lifelong—residents themselves. Or that there are other ways to determine citizenship without entering that information directly into a field on some form or computer screen.

An underlying concern Katz-Lacabe has with the Palantir contract is because so much of the analysis happens inside a black box. “We don’t quite know how much information they use and they don’t fully disclose how they reach the conclusions they do,” he said. “The company will tell you that's their secret sauce.”

Granted, Palantir is hardly the only Silicon Valley company with U.S. intelligence and surveillance links. Google, Microsoft and Salesforce have come under fire from their own ranks this year for contracts enabling the U.S. National Security Agency, the military and special forces, the CIA and ICE.

But this county has held itself to a higher standard by adopting policies protecting healthcare information and limiting police surveillance, Hernandez pointed out. She said the public also greater expectations as they become more aware of the role these technologies play in daily life—for better or worse.

“There’s already so much distrust in the government,” she said. “And with more light being shed on Palantir, I think it’s important for the county and anyone who contracts with those companies to tell us what they’re doing to protect people.”

> On the streets, each of those clients cost the public $62,473 a year in emergency services, according to the county; with a roof over their heads, that figure dropped to $19,767.

Oh, great!

Only $19,767!

How do we get to ZERO!!!

My new, innovative solution to the so-called “homeless” problem:

1.) RESERVATIONS. You know, reservations like where Elizabeth Warren’s “indigenous” ancestors lived.

2. BUSES. (a.k.a., “public transit”). Our modern, fuel-efficient and ecologically sensitive buses will scoop up the addled, disoriented street denizens who are unclear about where their home is, and whisk them in air-conditioned comfort to their NEW, PERMANENT home on the MITCH SNYDER RESERVATION in rural Arizona. Right next to the Navajo Reservation. And the Mitch Snyder Reservation will have amenities every bit as good as those on the Navajo reservation.

I have to be transparent and admit that this is not a completely original idea. I have discovered that neighboring cities and municipalities in California are already busing THEIR population of indigenous foragers in our direction.

It may be that the real permanent solution to the urban “homeless” might simply be a massive fleet of buses, permanently on the road, eternally cycling the paleolithic population from one encampment of SJW’s to the next.