Janice Lobo Sapigao didn’t expect her first year as Santa Clara County Poet Laureate to be sucker-punched by a global pandemic. But she’s determined not to let that stop her from getting South Bay kids to love their own words.

The Silicon Valley native took over the two-year poet laureate position in January. The job, an honorary post, comes with a mandate to increase residents’ awareness of poetry and celebrate the written word. Sapigao—a Filipina-American poet, author, writer, educator and active community member—has plenty of ideas about how to do that.

She plans to develop paid workshops that can ideally outlive her poet laureate tenure, invest in a couple local college students in need of a boost and create an intensive creative writing and poet laureate program specifically for young people.

“I hear too often—so much that now I know it’s a fact—that students are told that they’re not good writers and ... their stories aren’t worth sharing,” Sapigao said. “Sometimes I’ll ask them, ‘Who told you that?’ and there are one of two answers that I usually get. One is that they say ’Oh, a teacher told me, which I think is a devastation.”

But the most heartbreaking answer, Sapigao said, is when a student says they just know they aren’t a writer, or that their writing has no value. Sapigao said that is never the case.

“That makes me want to start this program because I think, too many, in too many ways, our youth are told that their voices don’t matter,” she explained.

Before the coronavirus, Sapigao regularly hosted and attended open mics from the Bay Area to L.A. and beyond. Now, the South Bay native spends most of her time coaching young writers, and working on her own art.

“Janice is on it,” said Mighty Mike McGee, who yielded his poet laureate post to Sapigao this year. “Initially I felt bad because the pandemic hit during her term, but she’s handling it very well. She’s getting a lot done for youth, and especially marginalized youth—the most overlooked voices.”

In addition to her laureateship, Sapigao also earned a $50,000 grant from the Academy of American Poets. The money can be used to pay herself, but also to create and fund programs to help other people improve their own talents.

Already, Sapigao established a memorial fund in honor of her late mother to award $750 to two college students with GPAs in the 2.0 range. She’ll use $15,000 of the funds to run a local youth poet laureate program and workshop series, which she imagines will mostly take place online due to Covid-19 restrictions.

“I want to hire local poets and have them teach writing workshops,” she said. “I also want to provide students who attend, and teams who attend, with stipends.”

Sapigao plans to appeal to the county to match her $15,000 to extend the scholarship into the future. “I want to make sure that they continue the program and what I am finding is that all of that is up to me,” she said.

The workshops would help budding poets learn their craft closer to home than she did, though her years at the University of California, San Diego, gave her a pivotal peek into a part of the state that felt worlds away from her Northern California roots.

Master the Craft

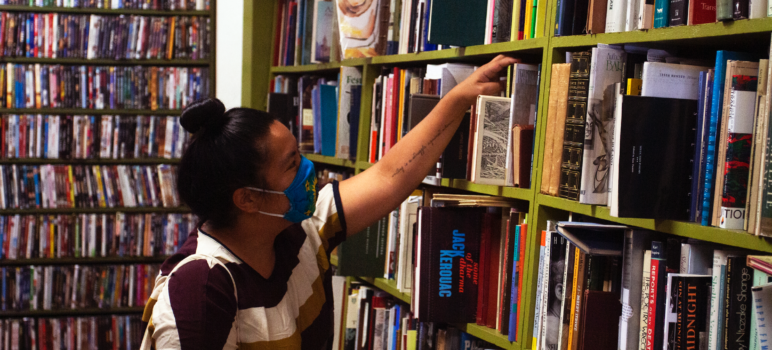

Janice Lobo Sapigao browses the bookshelves on Aug. 26 of Recycle Bookstore in San Jose. (Photo by Kyle Martin)

Being so near to the U.S.-Mexico border, where she met residents and learned about interest groups that were more heavily politicized, militarized and abundantly conservative than she’d experienced before. Sapigao learned to shape her culture shock into words and become the educator and poet she is now.

Sapigao moved home to San Jose with her new ethnic studies degree in 2010, while the Great Recession made job prospects scarce for new graduates. She worked for an Oakland publisher to ease the weight of her student loans while attending De Anza College and milling around the Bay Area’s writing and arts communities.

She later earned an MFA in writing from the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia.

As a college student, Sapigao frequented artist activist groups, including the SoCal chapter of Kabataang maka-Bayan, a Filipino youth-run revolutionary organization founded in 1964 in the Philippines.

Getting involved in such groups may prove more difficult for young writers today during the age of social distancing and digital learning. Meanwhile, the county—and country— are grappling with historic conversations about racism and police brutality.

The poet laureate plays an important role in times like this, and Sapigao’s work uplifts poets who would benefit from a little push and deserved recognition, McGee said. With Sapigao holding the reins for creative word-smithing in the South Bay, she gets to be “Mayor of Poetry Town” and “a beacon and a bullhorn for that town,” he added.

Lead the Way

Janice Lobo Sapigao browses the bookshelves on Aug. 26 of Recycle Bookstore in San Jose. (Photo by Kyle Martin)

Sapigao was already a beacon for Cindy Huynh.

As Huynh tells it, she would have dropped out of her PhD program at University of Utah if not for Sapigao’s words and artistry. At just the right time, she stumbled upon Sapigao performing a poem in Oakland following a book release on hip-hop representation in the Filipinx American community. Sapigao’s poetry made it into Huynh’s final dissertation.

“She was definitely among the people I felt like that pulled me through, even though she didn’t know,” Huynh said.

Huynh now teaches ethnic studies at San Jose City College and is a close friend to Sapigao. “She’s a really innovative educator,” Huynh said of her poet-in-arms. “She centers students in everything she does. She’s very mindful of how she speaks to students. I feel like she has her hand in so many different things, and someone like her is really needed in the things that she’s a part of.”

Sapigao said she wants to gas up more people to get where they’re going in this crazy, wild, violent and poetic world.

“People are angry … and I think that we have to make space for that. And I think writing and poetry become some of the space to hold it,” she said. “I think that this is going to be a time of great art, but that great art is going to come from great sacrifice, and already decades, if not centuries, of suffering that we have carried with us.”

She expects those themes to show up in young peoples’ art in the coming years, as cultures learn to coexist in the face of grave and imminent danger and without major support systems, like the U.S. government, to fall back on.

“I think Black Lives Matter, Black organizers, again, are being the ones to show us the way,” Sapigao said. “I feel that way about youth too. How many times do we have to get them to tell us to listen to them?”

Another leftie.

There’s just no diversity in the poet laureate community.