Ken Pritchett clicks his mouse and the logo of a Southern California police department pops up on a computer monitor the width of his shoulders. Another click and the image flips to a three-dimensional map. A glowing orange arrow indicates the direction a man ran as he tried to evade police.

“Right here, this is the path he took in the alley,” Pritchett said, switching from the map to a still image highlighting an object in the man’s hand. “Then you can see him turn toward the officers. He wants to die. This is suicide.”

This incident, like all of the videos Pritchett produces in his home office, ended in a police shooting. Pritchett has made more than 170 of these for police departments and sheriff’s offices, mostly in California.

The video flips again, this time to the display of a shuddering body camera worn by an officer sprinting down an alley. Commands are yelled, the person being chased lifts an object with his right hand, police fire their weapons, the man falls down.

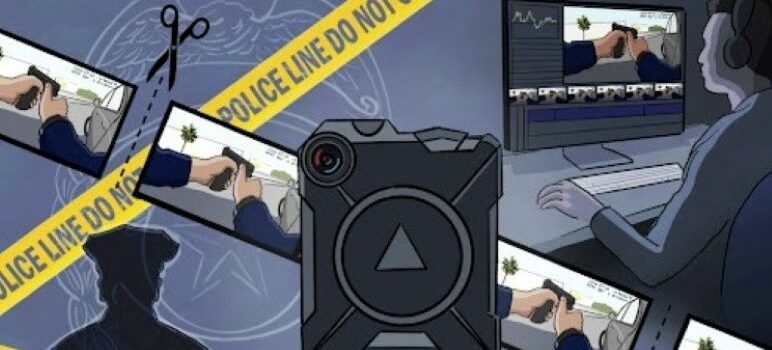

The video isn’t much different from hundreds of others produced since California passed a law in 2018 mandating police departments release body camera footage within 45 days of any incident when an officer fires a gun, or uses force that leads to great bodily injury or death. Like most other critical incident videos released by law enforcement agencies after a shooting, this one is a heavily edited version of the original raw video, created by one of the private contractors that went into business editing police footage after the law went into effect.

Pritchett, who makes more of these videos than any other private contractor in California, asked CalMatters not to disclose the name of the police department in order to preserve their business relationship.

The law has some exceptions, allowing departments to withhold video if it would endanger the investigation or put a witness at risk. Law enforcement departments often cite those reasons when regularly denying records requests by CalMatters and other news organizations. Of the 36 fatal police shooting cases since July 2021 being tracked by CalMatters, only three have responded with even partial records.

Instead, the public and the media must rely on edited presentations that often include a highlighted or circled object in a person’s hand, slowed-down video to show the moments when the person may have pointed the object at police and transcriptions of the body camera’s audio.

They are also the only documentation of a fatal police encounter that the public will see for months, or years, or maybe ever.

Since the advent of cell phone cameras and, later, police-worn body cameras, the public has had detailed access to violent police encounters in a way it never had before. After incidents including the livestream of the aftermath of the Minnesota police shooting of Philando Castile in 2016 and the helicopter footage of the Sacramento police shooting of Stephon Clark in 2018, states including California passed a host of laws aimed at using that technology to better judge the actions of officers.

Critics allege that the problem with the condensed, heavily-edited version of the body camera footage released by law enforcement agencies is that they shape public opinion about a person’s death or injury at the hands of the police long before the department in question releases all the facts in the case or the full, raw video.

They also point to particular incidents in which a department erased or failed to transcribe audio critical to understanding the case, did not make clear which officers fired their gun or cut the video at a critical moment. In one case, Los Angeles journalist Sahra Sulaiman has taken apart multiple videos released by the Los Angeles Police Department and found irregularities that she asserts are deliberate manipulations meant to justify officers’ actions. In response, she said the LAPD ignores her or directs her back to the video.

“To only release an edited version is not what we think is called for from the defendant’s point of view,” said Stephen Munkelt, executive director of California Attorneys for Criminal Justice, a Sacramento-based association of criminal defense attorneys. “If they’re editing things out, it’s probably the stuff that’s beneficial to the defendant.”

He also worries about the impact of the release of the body camera footage on a potential jury pool. Still, Munkelt said, some video is better than none, if only because defense attorneys have more grounds to ask a judge for the full, unedited video.

Former journalist works with police

In response to the 2018 body camera law, a cottage industry has emerged to produce these videos, though several larger law enforcement agencies produce theirs in-house. Pritchett works for Critical Incident Video, founded, not coincidentally, when the law went into effect in 2019. According to emails obtained by The Appeal and The Vallejo Sun, Critical Incident Video charges $5,000 per video.

Pritchett is a former journalist, and insists that he applies the same scrutiny and objectivity to these videos, paid for by police departments, that he did in his former life as a television reporter and anchor in Fresno and Sacramento.

“Virtually every article we’ve seen about what we do, somebody accuses us of spinning for the police department, but I have yet to ever see an example put forward that shows that we’re spinning anything,” he said. “And if they did, tell me, for God’s sakes. My entire goal is to make these straight, spin-free.”

Not every department uses Critical Incident Video, but for the dozens that do, Pritchett’s style is unmistakable: first, the map, then usually a transcription of 911 calls, then the body camera video. Pritchett said that, if he’s done his job well, he can help head off conflict between a law enforcement agency and the public.

“I think the main issue now is people come jumping to conclusions about what happened before they’ve seen the video, which is why we recommend that (law enforcement) always get that video out there as quickly as possible,” Pritchett said. “We have done quite a few videos where there was a social media public narrative about something that happened and the video clearly shows that that didn’t happen.”

Pritchett said that, before he made his first video, he learned by watching the videos that departments produced internally. He did not like what he saw.

“Basically, what we saw was the LAPD’s videos, and I didn’t like them … I probably shouldn’t have said that,” he said with a laugh. “But I remember seeing mugshots. I remember seeing information that was not really relevant (like) previous charges. I remember thinking the whole (video) that someone had a gun, until they told me at the end that it was actually not a gun.”

So, he has rules. He will not refer to the person who was shot as a “suspect.“ He will not use mugshots of the person who was shot. He will not display previous charges or convictions of the person shot, even if the department asks him to – something that he said cost his company a client when the police department insisted on including it. If an object was later found to be anything other than a gun, he demands that the departments tell viewers that up front.

Critical Incident Video’s process usually begins hours after a shooting. The police department or sheriff’s office will call Pritchett and send the raw footage, along with any witness video the agency has obtained. He combs through it, picking out the parts he believes are important.

He reads the initial police press release – “which is often incorrect,” he said – then reads any related media reports. He transcribes the audio of the body camera, creates a 3D map showing where the encounter began and writes a prospective script if one is requested, then tells the police to put it in their own words.

Pritchett said he pushes back against departments. Sometimes in a press release, agencies will say they immediately rendered first aid to a person they shot, but the video shows a delay.

“Sometimes that becomes a point of contention,” Pritchett said. “I’m looking at the video and say, well, how do you define immediate? We’ll change that. Like I said, we have to fight.”

The California Police Chiefs Association and the California State Sheriffs’ Association did not return voicemails from CalMatters for this story.

Assemblymember Phil Ting, a San Francisco Democrat who wrote the 2018 body camera law, said he has no problem with the condensed videos provided by law enforcement agencies after a shooting, because they’re much better than what was made public before the law.

“After the legislation was passed into law, we’ve seen so much more released and so much more video,” Ting said. “If a department is articulating why they acted in a particular way, that’s a good thing. They work for the public and we want accountability.”

Michele Hanisee, president of the Los Angeles Association of Deputy District Attorneys, said the release of the videos is a balancing act, forcing prosecutors to weigh the benefit of transparency against the potential harm of prejudicing the jury pool.

“While transparency promotes public confidence in the conduct of law enforcement,” Hanisee wrote in an email to CalMatters, “the pre-trial release of evidence has the potential to influence the testimony of witnesses, create bias in potential jurors, or create an environment that could justify a change in venue.”

Replaying LAPD shooting videos

Three hundred and sixty miles south of Pritchett’s Sacramento home office, Sulaiman, a communities editor for StreetsBlog Los Angeles, is in front of her own monitor, squeezed into the two-foot patch of carpet between her couch and a knee-high table on which her laptop is perched.

Her eyes, reflected back in the dark blue of a police uniform on screen, dart back and forth between the video released by the LAPD and the time code. She rewinds, presses play, pauses the video, rewinds again.

“Did you hear it?” she asks, then presses play on the video from December 2021. “Listen again.”

On screen is Margarito Lopez, a developmentally disabled 22-year-old sitting on a set of short stairs, holding a meat cleaver, bathed in blue and red light. Several LAPD patrol cars are parked in front of him, the officers shouting at him to drop the cleaver, as they have for at least five minutes.

Lopez stands. The police continue to shout in English and in Spanish. He holds the cleaver over his head. The body camera video’s transcription matches the words of the officers: “Hey, drop it, drop it, stop right there!”

Seconds later, officers fire live rounds, killing Lopez. Sulaiman rewinds again and turns up the volume on her laptop.

This time, a piece of audio that wasn’t transcribed by the LAPD is clear: “Forty, stand by.”

Forty, in this case, is code for a less-lethal foam projectile, a warning to other officers that what they’re about to hear are not lethal rounds.

“The protocol demands that they give the warning and then everybody stand down, wait to see what effect it has,” she said. “So he gives the warning and if you don’t know what you’re listening for, you just hear shouting. But then I realized that that’s what the warning was, and immediately, as soon as the less lethal is fired, it’s contagious fire because they didn’t hear the warning.”

Without that piece of audio, Sulaiman said, the video makes it appear that Lopez was shot after failing to comply with commands and advancing toward the officers.

“And that’s where they play with these transcriptions a little bit,” she said. “So that’s the kind of thing where if you have this different piece of information, that completely changes what this incident is.”

Sulaiman doesn’t believe the LAPD transcription left out the less-lethal warning by accident. The LAPD did not respond to specific questions from CalMatters about this incident or the video transcription.

Since the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in May 2020, Sulaiman has focused her work almost entirely on police violence.

Among her most thorough investigations was when she found the only evidence that an LAPD sergeant fired his weapon from his vehicle without stopping during a police chase on July 18, despite two other officers determining moments earlier that the man being chased didn’t have a gun.

The video never made clear which officer fired the shot that wounded 39-year-old Jermaine Petit, but in the reflection in the glass of the sergeant’s patrol car dashboard, she saw him holding up his gun and pointing it out the passenger side window. At the time of the shooting, the sergeant’s arm jerks backward. She said she had to watch the video several times, including at one-quarter speed, before she noticed the reflection.

She acknowledges that police have a difficult job in often-chaotic circumstances, trying to make life-or-death decisions. But that, she said, is their job.

“A lot of times they’ll say, oh, when we put civilians through these active shooter sort of scenarios, they just fire willy-nilly at people,” she said. “Well, yeah, ‘cause I’m not f——- trained.

“And when you go second-by-second through these, it is certainly a lot easier to play Monday morning quarterback. But you also see that LAPD is doing the same thing when they’re constructing these narratives.”

Sulaiman said the videos themselves are a mixed bag of consequences. She’s glad that there is some video evidence of the shootings released, but said the format is ripe for manipulation by the police.

“What these videos have taught me is how really skilled LAPD is at deflecting attention at deeper structural reform,” she said. “That they are very good at pointing the finger, at localizing blame on the things that take the least amount of tweaking to fix and deflecting any kind of interest in questions of structural reform.”

Both Sulaiman and Pritchett, in their respective jobs, have had to watch hours and hours of people being shot. The images they see are not blurred. People lie dying in pools of blood, people ask why they were shot, people shout for their mothers.

“It’s tough,” Sulaiman said. “I don’t know what else to say about it.”

When asked how viewing those videos affects him, Pritchett paused for several seconds, started to speak, stopped himself, then started again.

“To be determined.”

Nigel Duara is a reporter with CalMatters.