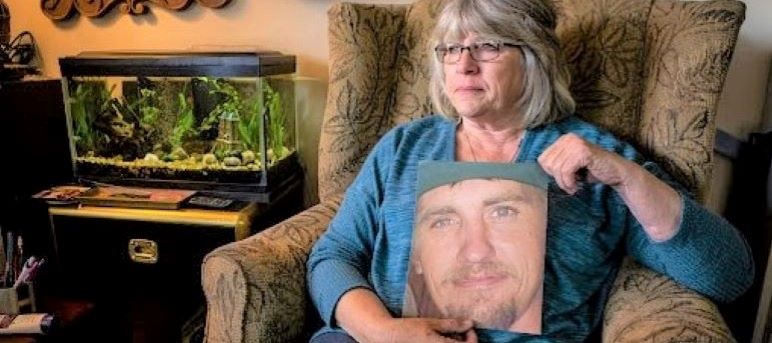

Three men in dark suits knocked on Pam Holland’s door one night last June. They told her that her son was dead, shot to death in a neighboring county by a sheriff’s deputy.

The shooting, they said, was being investigated under a new California law that requires the state Justice Department step in when a police officer kills an unarmed person.

Pam Holland hoped the investigation would be quick and fair. Her father had been a Kern County Sheriff’s reserve deputy. She grew up around cops. She thought she could trust them — but she also believed that police agencies protect their own.

“I was like, wow, that’s awesome, this is great, they’re going to take it out of the hands of the local cops, who would instantly feel anger toward my son without even knowing anything,” she said.

But an investigation that the Justice Department officers told Holland would take eight months is quickly approaching 12. Now, she is among several Californians whose family members were killed by the police in the past two years and just want the state investigations to end.

The Justice Department opened the program in 2021 to carry out a law enforcement accountability law that gained traction after a Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd. Attorney General Rob Bonta, who co-authored the law when he was in the Legislature, pledged that the investigations under the law created by Assembly Bill 1506 would be completed within a year. But some police shooting reviews have already stretched 18 months or more.

The oldest unresolved police shooting case is from August 2021, more than 21 months ago.

While the investigations proceed, the families and their legal teams have as much or as little information as the rest of the public and they cannot push forward with lawsuits against the policing agencies.

“I am at the point where I believe families have to pay a visit to Bonta in Sacramento,” said Jonathan Hernandez, a Santa Ana city council member whose cousin was shot to death in September 2021. “All of us, every family who’s waiting for 1506 investigations, if he doesn’t give us a response, we will give him a response.”

Bonta, the elected head of the Justice Department, refused to answer questions about delays in the investigations. His office responded to questions with an unsigned email.

The length of the Justice Department investigations leads to other impacts: District attorneys cannot develop police shooting cases to decide whether criminal charges against the officer or officers are merited until the Justice Department’s review is over.

In Holland’s case in San Bernardino County, the sheriff’s office said it could not issue a final verdict on its officer’s conduct while the state review is underway – an interpretation of the law that the Justice Department denied in a written statement to CalMatters.

The department “has no policy prohibiting a local law enforcement agency from completing its administrative investigation while our investigation is proceeding,” unnamed representatives for the Justice Department wrote.

In the meantime, the deputy who shot Holland is back on patrol duty.

Bonta’s predecessor, fellow Democrat Xavier Becerra, initially opposed the bill that led to the state’s role in police shooting reviews. Becerra argued at the time it would be too costly for the Justice Department, which is under the attorney general, to take on a responsibility that normally fell to local district attorneys.

One issue is money. The Justice Department asked for $26 million to pay for the new shooting investigation teams. The Legislature allotted half of that, about $13 million.

Becerra complained about that discrepancy to the bill’s author, Democratic Assemblymember Kevin McCarty of Sacramento.

The $13 million budget allocation “is significantly lower than our estimates and not enough resources to stand up professional teams to perform these new investigative and prosecutorial duties,” Becerra wrote to McCarty in January 2021. “As a result, the (Justice Department) will have limited capacity to implement this bill, short of redirecting resources from other essential, mandated work, which could compromise those operations.”

Now, the length of the state investigations is “longer than average” for police shooting cases, said California District Attorneys Association CEO Greg Totten, a former Ventura County prosecutor. He added that every case is different.

Prosecutors “try to move the cases as quickly as we can, but they’re not always straightforward,” Totten said.

Bonta’s office in the unsigned statement acknowledged the slower-than-expected pace of the investigations.

“As you know, the California Department of Justice requested more funding than we ultimately received to carry out our AB 1506 work, and we’ve had to adapt and make it work,” the statement read.

“This does sometimes mean that investigations may take longer to complete than they would with additional funding and resources, but we owe it to the families involved as well as our communities to ensure that each case is done right, and supported by a thorough, fair, and comprehensive investigation.”

McCarty said in a statement last week that the slow pace of investigations is a result of thorough work.

“It’s been slow to roll out and implement, but I still have confidence in the program — as it’s better to be right than to be fast,” McCarty said in a statement emailed to CalMatters.

“I feel for the families having to patiently wait, but rest assured, independent investigations for civilian deaths by law enforcement is vital in demanding more transparency and accountability.”

Pam Holland’s son, Shane, was an intravenous drug user with a litany of arrests and jail sentences. He had outstanding warrants and he ran from the police. She knows how all this looks. But she hoped the state, with its $13 million annual budget for police shooting investigations, would at least provide a dispassionate, thorough resolution.

Now?

“I wish they would have never gotten involved.”

A shooting on a desert highway

On a dark street in a San Bernardino County exurb, Shane Earl Holland gave a fake name to a sheriff’s deputy and ran.

Holland, 35, was a passenger in a car pulled over by San Bernardino County Sheriff’s deputy Justin Lopez about 2:30 a.m. one day last June. Holland had outstanding warrants. Lopez yelled at him to stop running and get on the ground. Holland replied several times, “I’ll shoot you.”

Lopez, according to audio from his tape recorder obtained by CalMatters, chased Holland on foot for one minute and 17 seconds, then fired six shots, killing him. Moments later, Lopez’s sergeant arrived at the scene.

“You good?,” asked the sergeant, whose name has not been released by the sheriff’s department.

“I’m good,” Lopez said, still breathing hard from the chase.

“Where’s his gun,” the sergeant replied. “Did he have a gun?”

“I don’t know,” Lopez said. “He said he was going to shoot.”

Pam Holland first heard that recording in January – a recording her daughter obtained from the Justice Department with a public records request.

“Honestly, like if there was no audio recordings, if I didn’t hear the audio recording, I would not believe the story,” she said. “If I didn’t hear it for my own self and they told me, well, you know, he said he was going to shoot, I wouldn’t believe it.”

On the recording, Lopez and his sergeant briefly discuss the injuries to Shane Holland’s body, mentioning that they can see his skull. She wants to know if he suffered.

Holland’s family has been assigned an advocate, who works for the Justice Department. Holland and two of her daughters sometimes do an imitation of the advocate’s frustrating responses to their questions: “‘I’m sorry, we can’t tell you that,’ ” they mimicked in chorus during an interview at Holland’s Tehapachi apartment.

Holland has questions about the night of the shooting. Why did the deputy chase the car’s passenger, leaving the driver to his own devices? Were her son’s pants falling off like they usually were? Did he have his hand at his waistband to hold them up as he ran? Did it look like he was reaching for a gun?

“I waver between thinking the cop needs to suffer, go to prison himself, to feeling bad for him,” she said. “And that makes me wonder what the hell’s wrong with me. He killed my kid. But he’s running in the dark, chasing someone who says, I’m going to shoot you. That’s not okay.”

When should police chase on foot?

Ed Obayashi, a former Plumas County Sheriff’s deputy who is now a nationally recognized expert in police use-of-force cases, also has questions about the shooting. CalMatters shared the tape recording of the shooting with him.

He broke the deputy’s decision-making into two parts: Why chase Holland, and why fire shots?

“Officers, it’s embedded in their DNA to chase,” Obayashi said. “That’s why we’re cops.”

But state and federal courts have held that simple fleeing is not a reason for a police officer to detain a person, said Obayashi, who also has a law degree.

Lopez, the deputy, told the driver that he had a reflective coating on his license plate, making it hard to read. Obayashi said he doesn’t understand what threat Holland posed to the officer when he fled.

“A physical threat, that hardly exists here because he’s running away,” Obayashi said. “And it’s inherently dangerous to be chasing anyone during the day, much less at night.”

The San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department has a policy for vehicle pursuits, but not pursuits on foot. In emailed responses to CalMatters’ questions, department spokesperson Mara Rodriguez said the department relies on guidance from the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, or POST.

The POST guidelines – which are merely suggestions and not mandatory – call foot pursuits “one of the most dangerous and unpredictable situations for officers.” They say an officer should have observed criminal activity before starting a chase.

“I just don’t see the legal justification for this shooting,” Obayashi said. “Fleeing alone is not a good reason to chase. Matter of fact, that’s no reason at all.”

But when Holland threatened Lopez, Obayashi said, his fate was sealed.

“I’m not taking that chance, if he’s saying he’s going to shoot,” Obayashi said. “It’s very easy for someone to pull out a gun and spray bullets behind them. The individual made a distinct threat and the deputy’s thinking, oh shit, this guy is going for a gun.”

For the deputy, the ramifications of using deadly force will be compounded by investigations by the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department, the local district attorney’s office and the Justice Department, said Brian Marvel, president of the Peace Officers Research Association of California.

“That adds up to a lot,” Marvel said. “Having to wait long periods of time and going through that is, it’s pretty rough. I think anybody under any circumstances having to wait those types of time frames, (it) takes a toll on your psyche, it takes a toll on your health and it’s difficult to get through.”

Marvel said it’s not surprising that the Justice Department investigations are taking a long time – the people doing the investigations are still learning to conduct them at this level.

“I think what you’re dealing with now is, you have an Attorney General’s office that has never done this before,” Marvel said. “So, in essence, you’re having to train up special agents to do officer-involved shootings. There is a skill associated with investigating not only officer-involved shootings, but just shootings in general, that the Attorney General’s office doesn’t have.”

Councilmember watched his cousin’s death

Another family who lost faith waiting for the Justice Department’s investigation has long roots in Orange County. Hernandez, the Santa Ana city councilmember, watched from behind a police barricade as officers shot his cousin, Brandon Lopez, 22 times after a police chase in Anaheim on Sept. 28, 2021.

Lopez, 33, had three outstanding warrants and was driving a stolen car that crashed at a construction site. During an hours-long standoff, police shouted commands to him, telling him to surrender. In a video presentation of dispatcher audio and body camera footage prepared by the Anaheim Police Department, police said Lopez was “smoking narcotics” inside the car and refused to leave.

Santa Ana police handed over the standoff to the Anaheim Police Department. Soon after, Anaheim Police officers fired a flashbang grenade and tear gas canister into the car. Lopez emerged from the car’s backseat moments later.

The officers called out that Lopez had a gun. Police fired multiple rounds, and Lopez is shown in the video falling to the ground. He died at the scene. He was unarmed.

“What they called a standoff was a public execution of an unarmed man,” Hernandez said. “The days of lynching have gone away and have evolved into the modern day police shooting.”

Hernandez ran in 2020 against an incumbent former Orange County Sheriff’s deputy on a police reform platform. He won by 9 percentage points.

At the scene before the shooting, body camera footage shows the councilmember in a T-shirt and shorts, asking to speak with his cousin and telling an officer he’s worried because “cops kill people every day.”

The officer responds: “People kill people every day.”

“Absolutely,” Hernandez said, “but you’ll get away with it.”

CalMatters requested raw footage, interviews and relevant documents associated with the Lopez shooting from the Anaheim Police Department in September. The department denied the request, citing the ongoing investigation.

When the Justice Department took control of the investigation, Hernandez said he was hopeful it would avoid the local politics of Santa Ana and Orange County. Unlike Holland’s family, Hernandez said his relatives do not think well of the police. He and Lopez’s mother, Johanna, told CalMatters they refused to speak with the local cops after the shooting.

“You cannot trust the people who just murdered your loved one to properly investigate each other,” Hernandez said.

Now, because of the delay, he wonders whether he and his family can trust the Justice Department.