Can a program created to help some of the most vulnerable during the pandemic successfully morph into permanently helping the unsheltered and homeless?

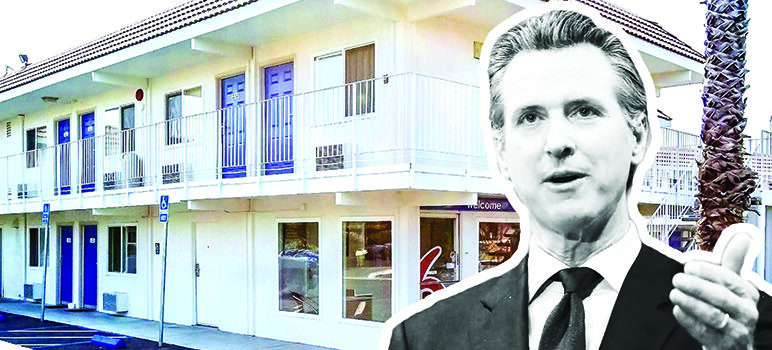

That’s what the state of California is exploring as it transitions its Project RoomKey—designed to temporarily house “medically vulnerable” people living in shelters or on the street—to Project HomeKey, which will purchase motels, hotels and apartment buildings for transformation into permanent housing.

Launched in April, Project RoomKey focuses on moving shelter residents from “congregant housing,” as well as moving unhoused people living on the streets, who were either at high risk of contracting Covid-19, or had already tested positive.

Although, according to state statistics, RoomKey has temporarily housed 14,200 “extremely vulnerable individuals” in three months, that represents only a small percentage of California’s estimated 151,000 homeless and unsheltered population.

Santa Clara County alone has about 8,000 who fall within that designation based on 2019 surveys. Alameda County has roughly the same number of unsheltered residents, while Contra Costa County has approximately 2,300.

Funded initially by $600 million of the $1.3 billion in newly available and eligible funding, part of the state budget Gov. Gavin Newsom signed June 29, HomeKey “will allow for the largest expansion of housing for people experiencing homelessness in recent history, while addressing the continuing health and social service needs of this vulnerable population,” according to a state press release.

Of the $600 million in available HomeKey grant funds, $550 million is derived from the state’s direct allocation of the federal Coronavirus Aid Relief Funds and $50 million comes from the state’s general fund.

Under the program, counties, cities and certain other entities will partner with the state to acquire hotels, motels, vacant apartment buildings, nonresidential properties and residential care facilities, which will be rehabbed into permanent residences. Project partnerships between local entities, including nonprofits, are encouraged.

“We don’t want to send people back to shelters and encampments,” Contra Costa County Supervisor John Gioia said in a recent interview.

By late June, Santa Clara County had leased nearly 700 hotel and motel rooms for homeless residents prone to Covid-19, though more than 20 percent remained empty, according to county officials. Alameda County, by about the same time, had leased 443 rooms for those vulnerable to Covid-19, of which 96 percent were in use, and had reserved another 198 rooms for those who tested positive for the virus.

But Bay Area property values present a major obstacle. Kerry Abbott, director of Alameda County’s Department of Homeless Care and Coordination, said the $100,000 “per door” guidelines from the state fit very few properties making HomeKey “an incentive.”

According to a July 24 state-sponsored webinar, those eligible can apply using more expensive properties, but a financial match will be required, which is why established partnerships may be the key to success.

State materials explain that, “counties and cities can access billions more in additional federal stimulus funding” to provide shelter for the homeless during the pandemic.

Gov. Newsom also announced $45 million in philanthropic support from Blue Shield and Kaiser Permanente. “These contributions, originally announced in January as part of the governor’s proposed Access to Housing Fund, were redirected by the companies to support the HomeKey effort,” state materials add.

Applications are now open for cities and counties, but “priority applications,” which will be funded using geographic criteria, are due Aug. 13. Final applications are due Sept. 29.

HomeKey would use CARES Act funds that must be spent by Dec. 30, meaning escrow must be closed on purchases. Priority will be given to “Tier One” projects, properties that can be occupied within 90 days, and where permanent housing is the goal.

Last week, San Jose Deputy Housing Director Rachel VanderVeen issued a request-for-information for hotel owners to submit funding applications by the Aug. 13 deadline.

Another question is how to effectively expand RoomKey’s focus to include those not eligible under the original guidelines. California Secretary of Business, Consumer Services and Housing Lourdes M. Castro Ramirez said during the July 24 webinar HomeKey designers were aware of the “deeply inequitable impact of homelessness on Black and Latinix communities.”

Geoffrey Ross, California Department of Housing and Community Development assistant deputy director, added that applications that actively address racial inequities are encouraged. Yet each city and county’s needs vary, he added, and “HomeKey has been intentionally designed not to be ‘one size fits all.’”

To some extent, Santa Clara, Contra Costa and Alameda counties will need to work together to help a population that includes transient people. Santa Clara County data shows that more than 80 percent of unsheltered people in the county originally became homeless in that county, leaving 15 to 20 percent who are transient.

Gioia and Abbott both commented on possible increases in the populations HomeKey will serve. “The state is releasing incarcerated people, many of whom have housing issues,” Gioia said. Abbott pointed to the possible end of eviction moratoriums, leading to more people losing their housing.

Of course, even an extremely successful Project HomeKey cannot solve the complex matrix of problems that creates homelessness. Job loss, unsustainably high housing costs, psychological and emotional issues, addictions, domestic violence—all of these and other factors contribute to someone, or a family, becoming homeless or unsheltered.

HomeKey is much more likely to form part of the complementary group of housing proposals, including the tiny homes, granny flats and garage apartments for which cities, counties and the state are beginning to rezone.

Residents in some areas will have to abandon long-held NIMBY attitudes to allow the changes to move forward. But there is reason to hope that a door has opened on what has seemed an intractable problem.

“We’ve long dreamed about scooping up thousands of motel rooms and converting them into housing for our homeless neighbors,” Newsom said in a recent media release. “The terrible pandemic we’re facing has given us a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to buy all these vacant properties, and we’re using federal stimulus money to do it. Hand in hand with our county partners, we are on the precipice of the most meaningful expansion of homeless housing in decades.”

Jennifer Wadsworth also contributed to this report.

Actually, not dumb.

> California Cities, Counties Target Homelessness with Newly Launched Project HomeKey

The taxpayers were ALWAYS going to pay to put mentally ill people and drug addicts SOMEPLACE.

Like, maybe, mental hospitals or asylums. Just get them out of the way so that they’re not public health nuisances or dangerous to themselves or others.

Unfortunately, we had to go through an enormous amount of theatrical virtue signalling and politically correct word smithing to arrive at the ACCEPTABLE set of words and language to allow the do gooders to feel good about themselves for what is — at the end of the day — WAREHOUSING of people who don’t have the mental or emotional capacity to provide for themselves.

We can’t call them “mental hospitals” or “asylums”; the’re “shelters”.

And we can’t call them “bums” or “hoboes”; they’re “unhoused” people “down on their luck”.

Instead of housing the “unhoused” in expensive “hotels” willy nilly in urban residential areas, it would mike better sense to actually build new, purposeful facilities, in surroundings suitable to their contribution to society, rather than in expensive prime residential areas among productive people trying to raise families, send kids to school, and make the economy hum.

What problem will it solve?

Neighbors complain about [formally] homeless now housed in the expensive downtown area on 2nd St. and at Donner Lofts. SJPD Chief Garcia stated it’s so bad, SJPD dispatches at least 3 officers instead of 1 for service calls.

SJ attempted to house chronic cases from St. James park. Almost 18 months after program launched, less than 50% of the apartments were occupied. Some could not be domiciled.

Other tenants complained of sanitary conditions, drug sales, prostitution, apartments were stripped of fixtures and appliances, etc.

The 2 year motel temporary housing program hasn’t worked in practice. Few success stories and they get evicted when the term expires.

The Salvation Army’s program has the highest success rate, but they eject those that don’t change their lives.

How about stopping the destruction of useful buildings at the old Fort Ord site and start thinking about a State Solution for all homeless. The location is ideal for homeless support housing, training and giving all the medical and social support needed in one place. The cost to renovate these buildings is minimal as compared to doings the same in the bay area. If you really want to remove a growing crisis from your neighborhoods try thinking out of the box and pay less with a better result. Not one size fits all, but it will help focus on locals displaced and senior citizens in need.

Makes a lot of sense.

Is there any way that local politicians or activists could get credit for “solving the homeless crisis”.

No, no, no. What about all the vagrant camps in front of homes and businesses? You know, the same homes and businesses owned by lawful, tax-paying residents. A time-bomb waiting to explode. These vagrants destroy neighborhoods, business districts, public trails, parks, creeks, etc. They illegally dump their garbage everywhere. They illegally steal from residents anything not nailed down. They illegally defecate/urinate anywhere. They illegally block sidewalks. No, it’s not illegal to be without a home, but everything else they do IS illegal. Homeowners and businesses have had enough! The elected officials that work FOR us need to do something now.

While true, they are there anyway and there is not much the city or state is willing to do about them status quo.

Second after the Boise Homeless Supreme Court Case determined the city could do nothing to keep homeless of the streets until they could offer alternate accommodations. The newly purchased hotels currently being half vacant is a feature, not a bug, because with vacancies come the ability to shoo them away from public spaces.

Hotel cap rates are usually pretty high and once the city owns the hotel, they vertically integrate middleman cost out of the equation, probably squeeze the assessor out of some valuation. It pretty much makes it undesirable for the tourist crowd anyway and massively reduces the improvement valuation.

Now, how well they will be maintained, etc is a different story.

Is it called Home Key or Room Key?

Sorry Joe Lopez: Sam Liccardo, Dave Cortese, Cindy Chavez, Raul Peralez, etc. don’t like proven solutions.

While not a silver bullet, these kinds of enforced residential treatment programs work. Some can’t be independent. That population was served by Agnews. Some could be and that population was served by Elmwood when it was a work farm before converted to a jail.

Work farms work better than any other approach. Not a panacea, but vastly better than the ‘3 squares and a cot’ currently used. The Salvation Army’s program and other proven ones are effectively work farms. And they publish data unlike taxpayer supported ones.