A year into the pandemic, San Jose’s Andrew Phan has gotten used to marking the end of his workday by cracking open a beer, usually craft and often locally made.

It’s a ritual that pairs neatly with his habit of catching up on the news and clips of The Daily Show with Trevor Noah or The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, mixed with a dash of doomscrolling after shutting down his work laptop at his kitchen-table-turned-office-desk. He always kept up with current events but the nightcap habit came with the pandemic, when the stresses of life felt “amplified.”

“Whether I’m working from home, or I’m physically in the office, I get home and I’m like, ‘What the hell happened today?’” he says with a laugh. “You pull [a beer] out and try to calm down or just enjoy the drink and relax the rest of the evening. It’s something new I never really thought about pre-pandemic.”

Phan’s hardly the only one who started going for an end-of-day glass of booze to dull the edge during the tumult of the past year. Online alcohol sales jumped 234 percent year-over-year in the early weeks of the pandemic, global data analytics company Nielsen Corporation reported in 2020.

The trend seems to have stuck. Many adult Americans said they were imbibing 14 percent more often during the pandemic—some much more than that—according to a September report in the journal JAMA Network Open.

On top of drinking more, Americans have spent the past year unearthing family recipes and learning to make their own bread until flour became almost as hot a commodity as toilet paper and hand sanitizer in the early days of the pandemic. They ate at restaurants less, adopted dogs at a record rate and became Zoom-savvy—or endured viral mishaps.

Those who could afford it upgraded living spaces and bought home fitness equipment instead of gym memberships, travel or new clothes, according to data from the Brookings Institution, JP Morgan and a recent survey by Ameritrade.

A year into the coronavirus era, this is daily life for many in Silicon Valley.

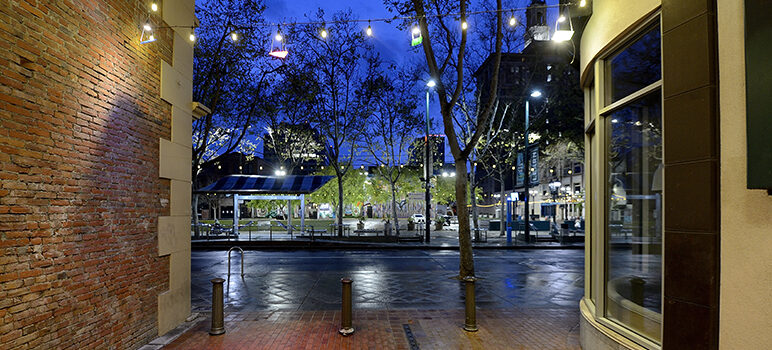

The impact of Covid-era lockdowns will no doubt linger for a long time to come. (Photo by Greg Ramar)

Habit Formed

Conventional wisdom holds that a habit takes about a month to stick.

So after 12 months of oscillating lockdown orders that kept people inside, away from friends and looking for comfort in the few places it could be found, those new routines must be all but cemented into place—right?

“Conventional wisdom is wrong,” declares BJ Fogg, founder of the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford University and author of Tiny Habits. “Habit formation depends on somebody's emotions as they do the behavior. … There’s more factors involved; the person, the action and the context are the factors that give a more nuanced view of it.”

One of the biggest factors in forming and keeping a habit, Fogg says, is a person’s environment, which includes places, people and culture.

The environment changed dramatically almost overnight during the pandemic, as workplaces shuttered, gatherings stopped and masks became mandatory. In turn, pandemic impacts became apparent at the start, from a rise in drug and alcohol consumption, to supply shortages of everything from disinfectants, office desks and, once the weather cooled, outdoor heaters.

Now, with vaccinations underway and health officials loosening pandemic restrictions, that environment is on the precipice of another major change.

“That means your habits are going to change whether you like it or not,” Fogg says. “The good is that because your habits are changing … you can now be in charge. You can design the new habits that you want and this is the opportunity to do it.”

Fogg says habits formed this past year aren’t necessarily here to stay, but people are also unlikely to revert to their pre-2020 lifestyles.

Some habits are harder to drop or pick up, he adds, and even when Covid-19 is under control, our culture could change forever in certain ways.

Some people, Fogg says, will probably return to old hobbies and habits easily, but many may never bounce back to 2019 levels of socialization or spending. Others will go the opposite way, embracing habits and activities even more. Most people will fall into all those categories—including Phan.

The 41-year-old self-described introvert says the pandemic left him even more cloistered than usual, and he’s ready to see friends more—once they’re vaccinated.

“Even though I'm introverted, it does take its toll,” he says. “I do need some outlet.”

One thing he won’t likely go back to, however, is the gym. The 24-Hour Fitness that Phan used to visit three or four times a week closed for good during the pandemic. He’s gotten comfortable with his at-home weight set and riding his bicycle more often.

Deserted streets were a defining feature of the early months of the pandemic. (Photo by Greg Ramar)

Economic Outlook

Such attitudes have left futurists guessing about what the short- and long-term cultural and economic impacts of the pandemic will be.

The prevailing question after the pandemic began spreading across the country and lockdown orders followed last March was whether the ensuing recession would be “V-shaped,” meaning it would come with a fast and sharp recovery, or “U-shaped,” meaning the painful downturn would stick around for a while.

Today, economists are generally optimistic, especially in Silicon Valley.

“This economy is unbelievably strong and resilient, it’s just incredible,” says Russell Hancock, president of research think tank Joint Venture Silicon Valley. “Silicon Valley’s economy is as strong as it has ever been. In fact, the tech sector had a record year any way you measure: stock market performance, IPOs, patent generation, venture capital formation, the number of unicorns—all of these things. Even during a pandemic, we continue to perform at record levels.”

Though the overall outlook seems rosy for the region’s economy, that doesn’t really tell the whole story, Hancock says. The pandemic sped up many of the changes that the region and country were already witnessing, including shrinking bricks-and-mortar retail and new remote-work options, which may now forever be altered.

Even more consequential for Silicon Valley, Hancock says, is that it also sped up the growing wealth and inequality gap.

He estimates that some industries, like restaurants and retail, will find a new equilibrium in the recovery after many retailers closed for good and residents grew accustomed to cooking at home and shopping less.

Some retail workers who once relied on high demand in those industries may have no jobs to return to right away—at least not any with livable wages.

“It's actually going to be more perilous because that sector ... won’t make a full and complete recovery,” he says. “We’ll find the problems still there, they haven’t gone away and we have to figure this out. We can hope that something will happen, but that something has to be amazing to overcome standard market forces.”

A recent report by Brookings Institution affirms Hancock’s assessment, characterizing Covid-19 as “a temporary shock to the global economy,” as it projects average American spending to reach 2019 levels again by 2023. The Brookings research assures the middle class will largely recover this year, but warns that “the average world citizen, however, will have lost two economic years.”

Brookings estimates that restaurants, hotels and transportation will bounce back relatively fast, before 2025. Other industries, however, such as personal care services, clothing shopping and even union dues will take much longer to recover fully.

At the same time, some sectors may contract as the economy improves.

Phan says he plans to cut back on his nightcaps as restrictions loosen. If others are like him—and Fogg thinks many may be—alcohol sales could dip again as people find more options for fun and relaxation.

Other cultural shifts may also be on the horizon. Fogg says he hopes showing up to work sick will no longer be seen as a badge of honor at so many companies. Hancock says fathers becoming more involved in child-rearing during the pandemic could forever shift cultural norms that traditionally placed more caregiving responsibilities on women.

Hancock, Phan and Fogg say they are all rooting for a future when mask-wearing is more socially accepted even sans a pandemic.

But one of the biggest cultural changes of the year could come in the form of normalizing better mental health awareness. Psychology experts around the world warn that declining mental health could become the next worldwide pandemic following a year of upheaval, loss and lingering uncertainty.

Phan says his perspective on mental health has certainly shifted. He’s thinking about seeking out therapy—something he says he hadn’t considered a year ago, but started mulling as the one-year anniversary of the pandemic lockdown approached.

“I can’t be the only one who feels this way,” he says.

“Everybody reacts differently to things, but I think coming out of this it’s probably good to try to assess, you know, ‘Where are you at mentally?’”

For some people it’s been terrible, for others great. Wife and I fall into the latter category while the kids (15 and 11) probably fall into the former. We’re still working (Via telework)

On a professional level, I’ve managed to become one of the most efficient people in my department. We have 2 categories of work we do, incidents and tasks. I’m first in both categories.

Incidents 33% ahead of second place

Tasks 75% ahead of second place

Not spending as much in gas every week, eating way better, not spending money on food at work. I feel better. No commuting, waking up an hour later, wearing my pajamas as I work. It’s just so much better than it was pre-pandemic.

We used to eat out ALOT, but now we’re cooking most meals. I’ve learned to bake. My bread is amazing, and my cinnamon buns were featured on the news.

Once I get full time telework locked in (Vs week on/Week off) I’m moving. Why stay here?

I fully expect responses of peoples terrible experience to follow.

Hey Robert,

Hate to disappoint you but I’m loving this COVID experience too. Working outdoors no problem + getting around town has been so much easier. I’m dreading kids going back to school clogging up the roads again. With any luck this new South African variant will prompt Commissar Cody to declare a new lockdown. Hopefully this mass hysteria will continue right? Fingers crossed!

One downside was flushing all our money down the toilet. Please, nobody tell Biden what comes after trillion.

John Galt >Hate to disappoint you but I’m loving this COVID experience too.

Heh awesome man. Ya while I may be excelling right now, many of my coworkers are not. National wants to reel everyone back into the office. I’m sort of reminded of what a coworker said to me when we first got our telework option.

“I TREAT MY TELEWORK DAYS LIKE A HALF DAY!”

I laid into him. “No man, we want to do the opposite, we want to show management that we’re better at Telework than in-office”

Unfortunately most of the department did the same as he did. Sure everyone showed up for the morning zoom meeting, but after that a lot of people were unreachable for the day. Their closure rates took a nosedive. I have a feeling this happened in more companies than just where I work. Too many people screwed up this opportunity to show management that we’re ready to telework as a society.

I feel ya on the people returning to the roads. I’m already seeing it. For a spell traffic was amazingly sparse, the way it should be. Slowly the road boulders and bad drivers have been getting back on the road.

I don’t know if I’d want another variant coming around, but I am hopeful that people that were proven performers teleworking will be able to find full time telework somewhere else after it all ends.

The rich got richer, the poor got poorer, and the middle class will pay the interest.

Californization of America.

Hope some of you at least got a few bitcoins when they were cheap…