Somehow, in the face of a $30-billion-plus deficit, the state’s public universities and financial aid programs got more money in 2023.

The University of California and California State University each received increases of 5% in instructional state support — for the second consecutive year. In exchange, the two systems must increase graduation rates, close the differences in graduation rates among racial and ethnic groups, and meet other conditions.

Lawmakers also beefed up support in a key department: housing. The state, after some doubt, continued its program of giving some campuses access to tens of millions of dollars each to build student housing so that low-income students can pay lower rents.

State lawmakers also preserved the Cal Grant, California’s marquee financial aid tool that covers undergraduate tuition at the UC and Cal State and awards about $1,650 in cash to eligible community college students.

The program was supersized in 2021 by expanding access to more than 100,000 community college students who were previously ineligible because of age and time-out-of-high-school restrictions. But a plan to expand Cal Grant to an additional 150,000 low-income students can only occur if revenue forecasts next spring say California can afford it. Meanwhile, lawmakers plowed ahead with expanding the Middle Class Scholarship, a revised state program that debuted this year and doled out an average of $2,000 to 300,000 UC and Cal State students, but none to those at community colleges.

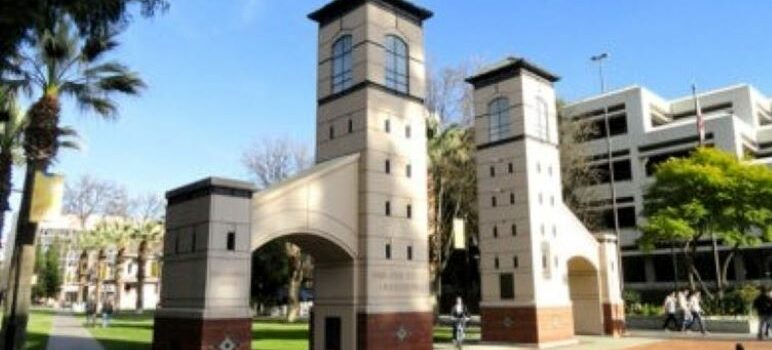

But the infusion of extra state cash isn’t enough to fully fund Cal State’s academic missions. In a display of fiduciary dread, the system reported in May that it’s short by $1.5 billion a year to properly educate its more than 400,000 students. So the system did what the UC did two years ago: approve multiple years of tuition increases.

The Cal State hikes, totaling 34% across five years that kick-in next fall, won’t affect about 60% of undergraduate students. That’s because their financial aid totally covers tuition. Still, the system’s students were furious and protested fiercely.

Siding with Cal State’s students were the system’s workers, including the largest union at Cal State, the California Faculty Association and its 29,000 members. While the system settled with most of the staff unions, it remains at an impasse with the faculty union, which in October gave its leadership the green light to call a strike if necessary.

How money is spent is a sore spot at the community colleges. The 116 campuses are bound by a law that says half of their primary state support must be spent on instruction. But the needs of students have evolved since 1961, when that rule arose. Internet access, books, emergency food support and so much more doesn’t fall under the so-called 50% rule.

The colleges are slowly rebounding from the enrollment collapse they suffered since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. To attract more students, they’re also experimenting with new ways of teaching students, such as avoiding classrooms altogether.

Major issues for 2024: The governor and legislators vowed in the past two years to beef up financial support for public universities and support more students financially. Those promises arose during an unprecedented revenue windfall.

Now the state is eyeing deficits, which will call into question whether California can continue to grow the educational budgets of the public universities while making good on a plan to expand financial aid to mostly community college students.

Labor strife may engulf the California State University as its faculty threatens to strike. Enrollment woes at the system and community colleges also remain a concern.

Mikhail Zinshteyn is a reporter with CalMatters.