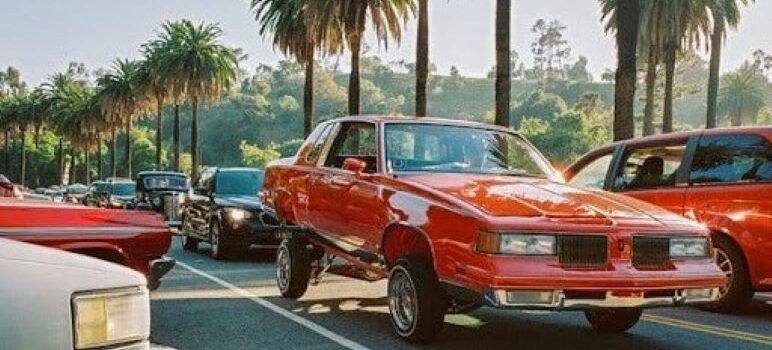

A line of cars glittered in the sun as they crawled just inches above the ground, gliding past a “NO CRUISING” sign at a popular park near downtown Los Angeles earlier this month. Bass sounds thumped from some of their speakers.

Other cars hopped up and down, their drivers smiling as they passed taco and ice cream vendors, and waved at spectators.

This largely Latino community of car lovers had gathered to spend a Sunday with friends and family. But to show off their cars, known as lowriders, some were technically breaking the law.

Lowriding — the practice of modifying classic vehicles by dropping their suspension and sometimes by adding hydraulics — has been part of California’s car culture since the 1940s.

Lowriders' place in popular culture found expression in the pop classic “Low Rider” by WAR in 1975. https://youtu.be/BsrqKE1iqqo

But in the decades that followed, bans were imposed on cruising by cities and counties that stereotyped lowriders as being associated with crime and gangs. The laws, which lowriders say are discriminatory, have long prevented them from parading their cars without the fear of being cited or towed.

San Jose was formerly known as the lowrider capital of California until 1986, when the city banned those cars and created “no cruising zones,” a ban often called racist and discriminatory.

San Jose overturned its ban on lowriders in 2022, and on Sept. 1 of this year city officials joined car enthusiasts in celebrating a first Annual Lowrider Day with cruising cars, speeches extolling Latino culture and crowds of spectators.

Gov. Gavin Newsom on Oct. 27 signed a bill into law repealing those bans and lifting a state prohibition on modifying a vehicle to significantly reduce its clearance from the roadway.

“We’re not gangsters, we’re not looking for trouble,” said René Castellon, the president of the Elegants Los Angeles Car Club, who drives a red 1965 Chevy Impala with a windshield sticker that reads “CRUISING IS NOT A CRIME.”

For months, he and thousands of other lowriders across the state have been advocating for the bill, which was introduced in February, and passed both the State Assembly and Senate with strong bipartisan support. The new law goes into effect on Jan. 1.

While Sacramento and National City joined San Jose in lifting the bans, in other parts of California, low-rider modifications and cruising— often defined as driving multiple times past the same spot within a set time period — remained illegal.

In Los Angeles County, the penalty is a fine of up to $250. Though the rules are not always enforced, some lowriders described being told to move on by the police, being ticketed or having their cars impounded, as well as being treated like a criminal just for enjoying a beloved hobby.

“I lost my license a couple times,” said Alejandro Vega, a custom car builder based in the San Fernando Valley, whose work has won numerous awards and has been displayed at the Louvre.

“They were stereotyping lowriders,” Vega, who is known as Chino, said of the police, who he said also impounded his car. “You could have passed 20 times in a regular car — they will never stop you.”

Vega, 51, moved to the United States from Mexico as a teenager, and said he was immediately drawn to lowriders for the way they stood out. Anybody “can drive a Bentley; not anybody with money can drive a ’59 convertible,” he said. “It’s in our blood.”

By most accounts, lowriding began in California among young Mexican Americans, who took a middle-class American symbol — the automobile — and turned it on its head. They began restyling older, more affordable cars with elegant upholstery, chrome and gold detailing, powerful sound systems and, in some cases, hydraulic suspension systems that could raise the car off the ground.

These flashy creations, made to be paraded “low and slow,” also became symbols of defiance that later spread to other marginalized communities across the United States and eventually as far as Japan.

In the postwar economic boom of the 1950s, the movement continued to grow with a surplus of older, more affordable cars, said John Ulloa, an expert in lowrider culture and history lecturer at San Francisco State University. “Necessity is the mother of all invention,” he said, describing the ingenuity of those who created “something beautiful out of something that was somebody else’s trash.”

Over the years, however, lowriding became a target of politicians who linked it to urban crime, and in 1988, state lawmakers passed a bill allowing local governments in California to enforce bans on cruising. Assemblyman David Alvarez, the San Diego Democrat who introduced the bill this year to end the bans, said they unfairly targeted a marginalized community and gave the police “another tool to intervene, to stop and to question individuals.”

Lori Maldonado, who identifies as a second-generation Chicana, said that for as long as she can remember, her lowrider community has been playing a “cat-and-mouse” game with the authorities, moving from one parking lot to another to avoid law enforcement.

“We’ve been hassled by the police ever since I was little,” Maldonado, 48, said, recalling how her family would place sandbags and heavy house speakers in the back of cars to weigh them down, dropping them closer to the ground.

She said that while it was true that some lowriders have past gang affiliations, many have reformed and see the hobby as an opportunity to express themselves, and to spend time with friends and family — especially as lowriding becomes increasingly popular among women. “The lowriding community brings us together,” said Ms. Maldonado, who drives a 1963 Impala that she has named Shady ’63. “We keep the peace.”

Vallerrie Martinez, a car builder and welder from South Central Los Angeles, said that she had been issued at least five tickets while lowriding, once while cruising along Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles, and had signed a petition in support of the bill.

“We can defend ourselves with the law now a little bit,” she said.

On a recent Sunday, Martinez, 32, watched at a hop competition in Ventura County, as one of the cars she had worked on lurched up on its back wheels, its nose tipping toward the sky.

“The cars are beautiful,” she said, describing the hard work and passion that people put into their vehicles, regardless of their background or income.

She added, “It’s like their Mona Lisa.”

Livia Albeck-Ripka is a reporter with The New York Times. San Jose Inside contributed to the story. Copyright 2023, The New York Times.

I remember how much of a nuisance these cars were back in the 80s here in San Jose. First of all, most of the modifications on these cars was illegal. Low rider cruising created traffic nightmares on the streets of San Jose, causing traffic jams everywhere there was cruising……..”Low and Slow” meant low and sloooooooooooow. The music coming out of most of these cars was extremely loud, making it difficult for anyone to hear anything else around them. First responders had difficulty navigating through and around areas where cruising was prevalent, delaying response time to those needing help. These are the real reasons why “No Cruising” zones were created, and why these cars were eventually banned. They were a nuisance, and hazardous to the community.

Let’s not forget about the impact on the environment. All that fuel, all that exhaust.

Oh Good, I’ll fire up the Hellcat! Thunder runs on Friday and Saturday nights, up and down first and second streets. Turn around at San Carlos, and drag racing at E Santa Claira St.

Gosh I miss the 70’s!

All the gang bangers we released from prison need something to do…