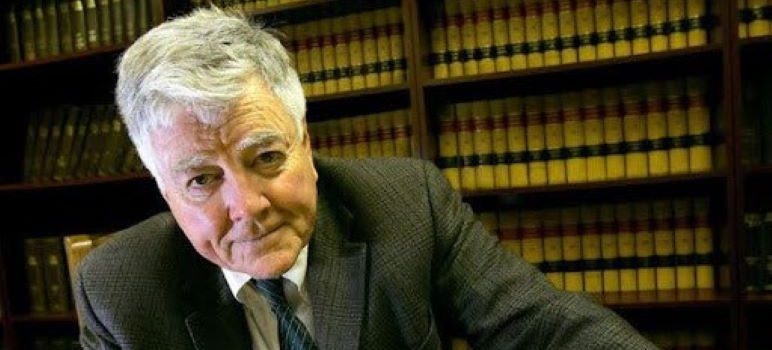

Pete McCloskey, a California congressman who raised a flag of rebellion against President Richard M. Nixon’s war policies in Vietnam with a spirited but futile race for the Republican presidential nomination in 1972, died on Wednesday at his home in Winters, west of Sacramento. He was 96.

His death was announced in a statement released on Wednesday by a family spokesman, Lee Houskeeper.

McCloskey, who represented the 12th Congressional District on the Peninsula for 15 years, from late 1967 to early 1983, was a liberal Republican who admired President John F. Kennedy, voted for environmental causes with Democrats and believed that the Republican Party had veered too far to the right.

McCloskey had lived for many years in Woodside and had a home in Portola Valley, as well as a farm in Rumsey, northwest of Sacramento. He was a trustee for the Monterey Institute of International Studies and led efforts to help veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars receive college educations on their return from duty.

In July 1971, with the nation divided over the war and Nixon heavily favored for re-election, McCloskey, a then 43-year-old Korean War hero and two-term congressman best known for defeating Shirley Temple Black in a special election, launched his quixotic quest for the Republican nomination.

He had no money, party support or realistic prospects. But he had gone to Vietnam three times, and in campaign appearances he vividly portrayed the war’s “cruelty and futility,” as he put it, evoking cluster bombs that killed or maimed anyone within 25 acres, and napalm strikes that burned all within 150 feet at 2,000 degrees. Tens of thousands of Vietnamese and Americans were dying in a war that could not be won, he argued.

“To talk, as the president does, of winding down the war while he is expanding the use of air power is a deliberate deception,” Mr. McCloskey said. “I’ll probably get licked, but I can’t keep quiet.”

There were comparisons to the 1968 antiwar campaign of Senator Eugene J. McCarthy, whose success in the New Hampshire primary contributed to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s withdrawal from the race. But McCloskey won only 20 percent in New Hampshire and gave up, though his name appeared on ballots in other states. Nixon went on to win the presidency in a landslide, defeating Senator George McGovern, before resigning in disgrace in 1974 in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

While his presidential run brought him national prominence, McCloskey was known in later years for environmental legislation. His bills included the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which has become a shield for the habitats of birds, alligators and other species. He was co-chairman of the first Earth Day, in 1970, and received awards for environmental service.

He also wrote books, including “Truth and Untruth: Political Deceit in America” (1972). After leaving Congress, he practiced law in Redwood City, Calif., bought a farm in Yolo County and lectured at colleges and universities in the Bay Area.

Paul Norton McCloskey Jr. was born in Loma Linda, Calif., on Sept. 29, 1927, to Paul N. and Vera McNabb McCloskey. His father and grandfather were lawyers and Republicans. Pete, as he was known, attended a military academy in San Marino, graduated from South Pasadena High School in 1945, joined the Navy and attended Occidental College and the California Institute of Technology under a Navy program. He graduated from Stanford University with a bachelor’s degree in 1950.

He and Caroline Wadsworth were married in 1949 and had four children. The marriage ended in divorce. He later married Helen Hooper. He is survived by his wife; his children, Nancy, Peter, John and Kathleen McCloskey; and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

A square-jawed man with a military bearing, McCloskey joined the Marines in 1950, when the Korean War broke out. The next year, he was wounded leading a rifle platoon in a bayonet charge to capture a strategic hill, an exploit detailed in his 1992 book, “The Taking of Hill 610: And Other Essays on Friendship.” He won the Navy Cross, two Purple Hearts and the Silver Star and served for many years as a Marine reserve officer.

After earning a law degree at Stanford in 1953, Mr. McCloskey was a deputy district attorney in Alameda County until 1954. He practiced general and environmental law in Palo Alto from 1955 to 1967, and lectured on legal ethics at the Santa Clara and Stanford law schools.

In 1963, Charles Daly, a Marine buddy then on the White House staff, put Mr. McCloskey on a list of lawyers invited to a White House conference on civil rights. President Kennedy’s address to the gathering inspired him to enter politics, McCloskey said.

His chance came in 1967. He was elected to Congress from San Mateo County to fill a vacancy created by the death of Representative J. Arthur Younger, upsetting Black and other candidates. He went to Washington as a fiscal conservative but as a liberal on racial, antiwar, environmental and other issues. He was the first House member to call for Nixon’s impeachment in the Watergate scandal.

He was re-elected seven times, but was not a candidate in 1982. Instead, he lost a crowded primary race for the United States Senate to the mayor of San Diego and a future California governor, Pete Wilson. Wilson went on to win the Senate seat in the general election, defeating the Democrat Jerry Brown.

In 1987, McCloskey was sued for libel by the television evangelist Pat Robertson, then running for the Republican presidential nomination. After Robertson claimed that he had been a combat Marine in the Korean War, McCloskey, who had been in his unit, contended that Robertson’s father, U.S. Senator A. Willis Robertson, a Virginia Democrat, had used his influence to keep his son out of combat.

With many other former Marine officers willing to testify that Robertson had avoided combat duty, Robertson dropped his $35 million suit in 1988 and agreed to pay McCloskey’s court costs, saying he could not pursue the suit and run for president at the same time.

But it was a clear victory for McCloskey, who said he had unmasked Robertson as “the fraud he is.” (Robertson, who quit the presidential race, did serve in Korea, but chiefly as a supply officer far from combat duty.)

Attempting a political comeback in 2006, McCloskey lost a primary fight against Rep. Richard W. Pombo, a seven-term Republican who opposed environmental reforms. McCloskey, ever the maverick, endorsed the Democrat, Jerry McNerney, in the general election, and Pombo lost. The next year, at age 79, McCloskey switched his affiliation to the Democratic Party.

“The new brand of Republicanism,” which he described as hostile to progressive causes, had finally led him to abandon the party he joined in 1948, McCloskey wrote in a letter to The Tracy Press, a California weekly whose articles and editorials were widely discussed in news and opinion forums in the state.

McCloskey and Helen McCloskey are the subjects of a documentary film, “Helen and the Bear,” released recently by his niece Alix Blair, a filmmaker.

“Just as he lived his life with courage, action, and compassion,” Ms. Blair said in the family statement, “Pete brought those qualities to their marriage. The film is a celebration of his open heartedness.”

Robert D. McFadden is a reporter with The New York Times. Copyright, 2024, The New York Times.

I wasn’t quite old enough to vote in 1972, but I thought Pete was a hell of a man to go up against Nixon. Later I registered as a Republican a couple of times specifically to vote for him in the primary. I’m proud to have had him as a local U. S. Representative and can’t say so much about our current crop.

He was a good man and had real integrity. My mom was a lifetime democrat but had him at our house once to meet constituents. It’s a shame he was forced to leave politics early.