California’s app-based corporate luminaries just waged the most expensive state ballot measure campaign in U.S. history—and it paid off big time, allowing those companies to thwart the will of all three branches of California government.

By approving Proposition 22, voters allowed companies such as Uber, Lyft and DoorDash to avoid a 2019 California labor law that would have required them to treat drivers, shoppers and similar gig workers as employees.

Nor was that the only instance in which a well-financed and aggrieved industry appeared to have persuaded voters to overrule lawmakers. Voters also rebuffed Proposition 25, blocking a cash bail ban that state lawmakers passed in 2018 that otherwise would have driven the state’s bail bond industry out of business.

Legislators also opted to ask voters to reinstate affirmative action by placing Prop. 16 on the ballot, yet it trailed in every pre-election poll, By the morning after, it was defeated.

On two other measures, California voters continued to distance themselves from the state’s tough-on-crime approach of prior decades. They passed Proposition 17, giving people on parole the right to vote, and they voted down Proposition 20, opting not to increase penalties for shoplifters and probation violators.

California voters also haven’t changed their minds much since 2018. Again this year, they rejected a measure that would let cities expand rent control, Prop. 21, and another, Prop. 23, that would have slapped kidney dialysis clinics with new regulations. The Associated Press called these state ballot props within a few hours of the polls closing.

Here’s what we don’t yet know: Pretty much everything else.

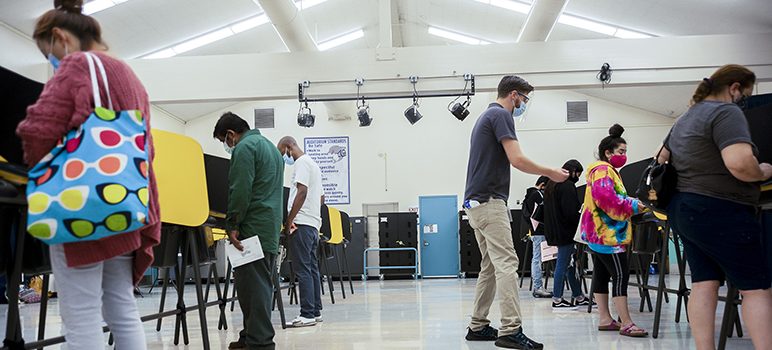

California voters are used to waiting for their results. Even before the threat of viral contagion convinced state lawmakers to send every active registered voter a ballot in the mail, three out of four voters did so.

But this election—like everything else this year—is different.

An unprecedented surge in early voting means California should be able to count a larger chunk of its ballots earlier than usual. That surge, plus the president’s habitual denigration of voting by mail, has flipped the script: This year the first returns were thought to favor Democratic candidates and causes.

That plus the global pandemic, a president who has repeatedly insisted that he may not accept the certified results of the election, and sizeable minority of California voters who said they believed the election wouldn’t be held fairly and transparently.

So, yes, uncertainty abounds.

Of the other tidbits of certainty we have, none are particularly surprising:

- Democratic presidential contender Joe Biden and his running mate, California U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris, won the vast majority of votes in the state.

- The California Senate and Assembly will remain firmly in Democratic hands.

- Turnout across the board was high.

If some of that sounds a little bit vague, it’s because there are lots of questions we still don’t have clear answers to. Below are a few of the big ones.

Congress: Is the blue wave here to stay?

Two years ago, California voters cut the state’s Republican congressional delegation in half. Propelled by anti-Trump fervor, voters in longtime GOP bastions—Orange County, suburban San Diego and the Central Valley—replaced seven of the state’s 14 Republican House members with Democrats.

The question: Can those members, now with records to defend, hold their ground? Or put another way: Was the blue wave just a one-off? Or a long-lasting realignment?

In at least a few districts thus far, the new blue hue seems to have left a permanent mark.

- Katie Porter, a prominent House progressive representing a district where Republicans still narrowly outnumber Democrats, won easily.

- Josh Harder in Merced beat back a challenge from Republican Ted Howze, who lost the endorsement of the GOP establishment over a series of racist social media posts.

- Mike Levin of Orange County also was maintaining a strong lead over GOP challenger Brian Maryott.

The three most contentious Democratic trophies from 2018—Harley Rouda and Gil Cisneros in Orange County and especially TJ Cox in Kings County—looked to be in potential peril as counting continued.

In 2018, a few races weren’t called for at least a week after the polls closed. Less than three hours after the polls closed, Cox fell behind former Rep. David Valadao. Given the expected blue hue of the early vote, that spelled trouble for the Democrat seen as the most vulnerable of the Democratic newbies.

The two parties are also still waiting on what might be the most potent symbolic battle of all: Congressional District 25. That’s the Simi Valley district where Democrat Katie Hill handily unseated a Republican incumbent only to step down after nude photos and rumors of her affair with a campaign staffer were leaked online. Democrats had teed up Hill’s successor in Assemblywoman Christy Smith, but she lost the special election in a May contest against Republican Mike Garcia.

Smith, with the backing of Democrats from across the state and county, has spent the intervening months trying make sure Garcia’s stint in Congress lasted no longer than eight months. “As a California state Assembly member who was declared the victor nine days after Election Day in the last cycle, I know how incredibly important it is to let the process play out and let the county officials do their thing,” Smith said at a press conference earlier in the evening.

The propositions: $780 million—what was it good for?

We know California is big and expensive. But of the top 10 most expensive campaigns in state history, four were this year. The total mountain of money raised for and against the 12 statewide proposition campaigns hit about $780 million.

Even among this year’s colossal money sucks, one of them was not like the other. Yes on 22, the campaign funded by Uber, Lyft and Doordash, spent more than $200 million — almost a third of the money spent by either side of any of the state ballot campaigns.

Alex Stack is spokesperson for Yes on 15, the split roll measure that would increase property taxes on large commercial properties. As the election concluded he sounded almost wistful: “In terms of state measures throughout the country, we’re the second highest in terms of spending on both sides. We could have been first.”

The fate of Prop. 22 will likely be a cautionary tale about the role of money in politics. Its success will offer another confidence boost to big businesses and organized labor hoping to fund an end-run around legislation and court rulings they don’t like.

And Trent Lange, president of the California Clean Money Campaign, doesn’t expect 2020’s record of $780 million to last long.

Even if it’s not a sure thing, “deluging voters with often misleading information” to win a particularly valuable state policy will always tempt well-financed special interest groups, he said. “It’s likely to get worse every election.”

The legislature: Dems will still run Sacramento, but which kind?

No matter the outcome, Democrats will still hold commanding majorities in both the state Senate and Assembly. Even if Republicans were to win all of their target seats and keep the ones they’re defending—and preliminary results suggest that’s unlikely—Democrats would still hold more than 70 percent of seats in both chambers.

What isn’t clear: just how large next year’s Democratic supermajorities will be and what kind of Democrats they’ll include.

Another sizable blue wave would send more GOP incumbents across Central and Southern California into involuntary retirement. That would bolster the chamber’s Democratic ranks—and its representation of moderate suburbia.

The most expensive of these contests was the tussle for Senate District 29. In 2016, Democrat Josh Newman won an upset in this once-solidly Republican stretch of Los Angeles and Orange County. In the summer of 2018, he was recalled and replaced by his former opponent, Ling-Ling Chang.

But some of the most contentious legislative fights are taking place within the Democratic Party. The outcomes could do more to reshape the politics of the Capitol than any of the partisan face-offs:

- In Stockton, a win by business-backed Carlos Villapudua over San Joaquin County Supervisor Kathy Miller would expand the party’s “mod caucus” in the Assembly.

- If incumbent Assemblyman Reggie Jones-Sawyer is picked off by the more moderate Efren Martinez, that would be another win for business. It would also serve as a reminder of the changing ethnic composition of this section of south Los Angeles which is now roughly 75 percent Latino. Jones-Sawyer’s election night double-digit lead spells a likely win for the progressive caucus—and the California Democratic Party establishment that rushed to the incumbent’s defense.

- In San Francisco, state Sen. Scott Wiener, the most prominent voice in the state in support of more housing development, fended off a 25-year-old Democratic Socialist, Jackie Fielder. Wiener’s allies in the building industry, wary of an Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez-like upset, spent the last few months bolstering his campaign.

Ben Christoper covers politics and elections for CalMatters, a nonprofit nonpartisan media venture.

> But some of the most contentious legislative fights are taking place within the Democratic Party.

No one else matters in the one-party autocracy of California.

Too bad all the money that is wasted in politics isn’t better spent in helping the poor.