His swollen joints ached and the world rocked back and forth around him as he stood for hours at his day job as a security guard at a local university.

The college senior had been visiting a doctor at a nearby clinic every other week, searching for answers about why his body was failing him.

But as a Black man, Josh Edwards—whose name has been changed to protect his privacy—faced diagnostic hurdles that his white counterparts didn’t. He struggled to convince doctors to run tests on him and felt physicians’ judgmental eyes as they scrutinized whether he was just angling for pills.

Despite living in excruciating pain, Edwards pushed on with work and school. The son of a small business owner whose business had capsized years prior, he had no safety net to fall back on. He needed health insurance and a paycheck to help him complete his degree in human services, even if that meant finding a wall to prop his deteriorating body up against while on the job.

Finally, after visiting a new clinic in a predominantly white neighborhood, Edwards received a diagnosis: he had an autoimmune disorder.

“I was taking sick days off because my body and joints were swollen and I had vertigo and a ton of other inflammation issues that later the rheumatologist told me was present, but I didn’t know at the time,” he says. “I would just work and go home and sleep until I had to work again. I wasn’t able to do anything.”

But Edwards eventually ran out of sick days, and was given his pink slip. He stayed with a distant family member for some time after, but eventually was asked to leave after his relative said they needed more space.

Since then, Edwards—who is now 37—has bounced between couch surfing, staying in shelters, and sleeping in his car or on the streets. Getting a full night’s rest on the streets isn't easy, especially as a Black man.

“You wake up almost every hour for one reason or the next,” he says. “It’s not just that it’s cold, but you’re worried about other homeless people or somebody that would rob you. Or you’re worried about the fact that you’re in a sleeping bag and a cop approaches you and can’t see your hands and just shoots you.”

When he’s not looking over his shoulder for the police, he has his health to worry about. It took him four years before the state of California approved him for disability insurance. But even that hasn’t covered the cost of all of his medications, forcing him to trade his food stamps for cash to cover the rest.

In Santa Clara County, the number of homeless men and women living on the streets has exploded in recent years. The 2019 point-in-time count reported a record 9,706 homeless residents, 19 percent of whom are Black. That’s compared to 14 percent of 7,394 homeless residents in 2017 and 16 percent of 6,556 homeless residents in 2015.

That growth has come with deadly consequences—especially for Black men and women.

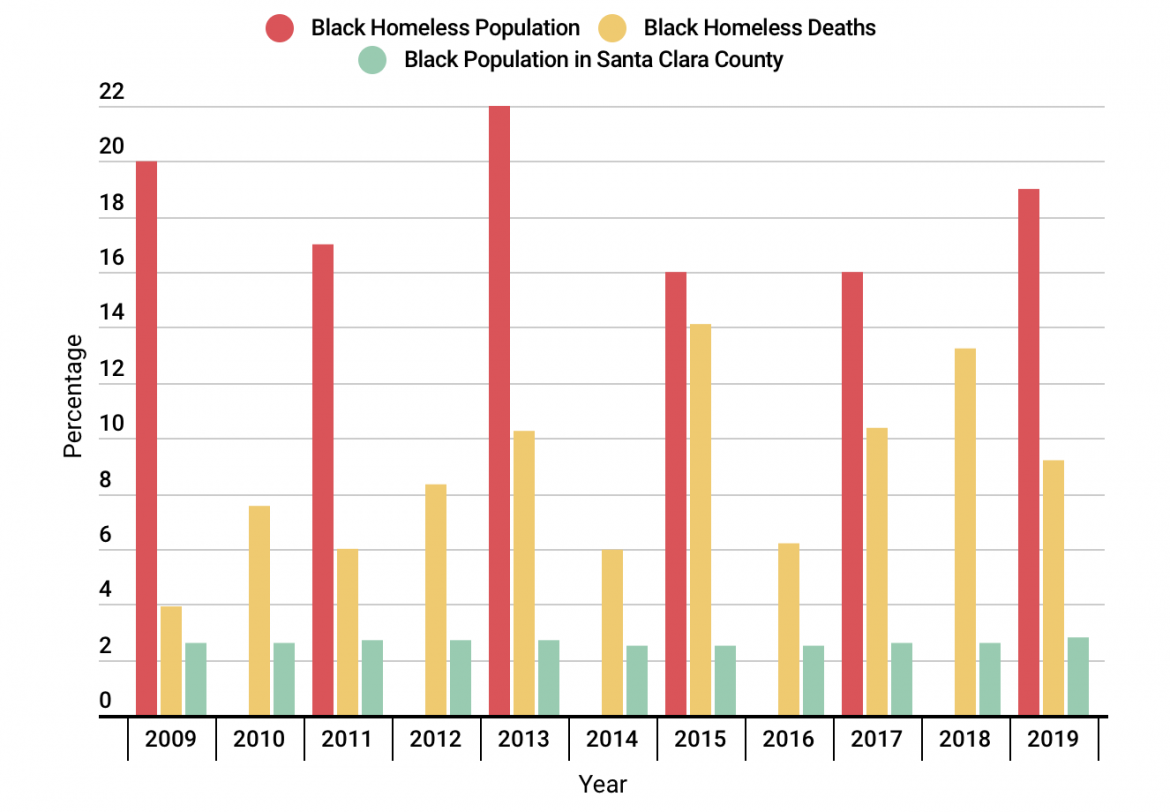

A San Jose Inside analysis of death records from the Santa Clara County Medical Examiner-Coroner’s Office found that the number of homeless individuals dying on the county’s streets has grown on average 13.79 percent year over year from 2009 to 2019. And Black homeless men and women are dying at disproportionate rates compared to their white and Asian counterparts.

Over the last decade, African Americans have made up anywhere from 2.5 to 2.8 percent of the county’s nearly 2 million residents, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. But homeless Black Americans have been dying at a rate two to five times higher than that percentage.

Racial Reckoning

Over the last few months, the U.S. has faced a new reckoning over racial justice with the killings of Ahmad Aubery in Georgia, Breonna Taylor in Kentucky and George Floyd in Minnesota—all unarmed Black men and women. Their deaths ignited nationwide protests and calls to defund the police, shining a light on racial inequities that have plagued communities of color for centuries.

In the United States, African Americans continue to be overrepresented in the homeless population. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2019 Annual Assessment Report to Congress found that 40 percent of people experiencing homelessness last year were Black, compared to the 13 percent of the national population that they make up. For families with children, that number is even higher, with Black families making up 52 percent of families experiencing homelessness.

Dr. Margot Kushel—who heads up the University of California at San Francisco’s Benioff Homeless and Housing Initiative, and has been studying homelessness for more than two decades—says the country’s homeless crisis is interwoven with structural racism.

“Until relatively recently in our country’s history, Black Americans have been excluded from home ownership,” Dr. Kushel said. “Because of that, not only did Black Americans not own homes, they lost the ability to build wealth [as] white Americans built their main source of wealth through homeownership.”

Starting in the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration refused to insure loans to African Americans who wanted to purchase homes in predominantly white suburbs. The practice, known as “redlining,” was phased out three decades later with the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

But redlining, coupled with other attempts by federal, state and local governments to prevent African Americans from moving into white suburbs, has had trickle-down effects that have left neighborhoods across the country still segregated to this day.

Dr. Brian Greenberg, vice president of programs and services at the homelessness non-profit LifeMoves, says income disparities often parallel racial inequities in society.

“Homeless folks tend to grow up in lower income ZIP codes,” he said. “People in lower income ZIP codes tend to have less access to healthcare, less access to a quality education, less access to nutritional food and limited access to upward mobility. When you grow up in a lower income ZIP code and you have less access to healthcare, education [and] nutritional food, those disparities tend to have lifelong impacts and implications.”

Over the years, these systemic barriers have created a smaller social safety net for Black Americans compared to their white counterparts.

As a result, Dr. Kushel says that white homeless individuals are more likely to have challenges with mental health or substance abuse. “We didn’t see that so much in the Black community where we saw it was just low-wage workers who had an injury or they got sick or their supporter got sick or their partner died,” she says of her research. “One relatively small thing pushed them out into homelessness.”

An SJI analysis of death records revealed that the rate of Black homeless deaths is alarmingly disproportionate to the percentage of African Americans in the county over the last decade. (Source: Santa Clara County Medical Examiner-Coroner)

Starting Over

In Silicon Valley, the high cost of living has triggered an exodus of Californians fleeing from the Golden State in search of a more affordable place to live. But for Edwards, his rare and chronic illness has prevented him from relocating to a place where he can afford four walls and a roof over his head.

The standard of care in some of the cities he’s considered moving to just aren’t up to par and lack the resources to treat his condition. As a Black man, moving also means reliving the trauma of starting over from square one.

“Once you have someone who actually sees you as a person, as a Black person, it’s a big fucking deal and it takes a long fucking time,” Edwards says. “When you do meet that [doctor], it’s very difficult to consider going somewhere else after that.”

Despite having access to doctors who can treat his condition, the day-to-day wear and tear of living on the streets has taken a toll on his health. He previously snagged a coveted bed at a shelter in Sunnyvale, but his compromised immune system couldn’t handle being in such close proximity to others.

“I had to start sleeping in the car again, because I couldn’t deal with being sick constantly,” he said.

According to the 2019 point-in-time count, 24 percent of Santa Clara County’s homeless population suffers from a chronic illness. Coupled with exposure to the elements and the lack of access to healthcare, the life expectancy of people experiencing homelessness is around 20 years less than non-homeless individuals.

Over the last decade in Santa Clara County, the average age of death was 53.8 years for homeless men and 50.3 years for homeless women. In the U.S., the average life expectancy is 81.1 years for women and 76.1 years for men.

San Jose Inside’s analysis of cause of death for homeless individuals over the last decade found that drugs or alcohol were listed as the main or contributing cause of death for 38.1 percent of deaths. Heart-related conditions such as cardiomyopathy, heart disease and congestive heart failure were listed by the coroner as the main or contributing cause of death in 20.4 percent of cases.

For African Americans, heart conditions were listed as the main or contributing cause of death in 26.9 percent of cases. In 2017, in the U.S. general population, African Americans were 20 percent more likely than their white counterparts to die of heart disease.

Alma Burrell, the South Bay regional director for the Roots Community Health Center in San Jose, attributes the disproportionate number of African Americans dying from heart disease to higher stress levels and structural racism. The Oakland based non-profit was founded in 2008 and works to rectify health disparities and aids Black families in navigating the healthcare system.

“When [Black] women’s amniotic fluid has been measured, ours tends to have more stress,” Burrell said. “We are basically bathed in a toxic environment in utero and it causes us to be more sensitive to stress once we’re born. I think a lot of it has to do with what we’re living through.”

For Black homeless men and women who have frequent encounters with the police, lack access to medical care and are constantly exposed to the elements, the compounded stressors can turn deadly.

But having access to medical care doesn’t necessarily improve health outcomes. From the Tuskegee Experiment that studied the effects of untreated syphilis on African American men to the unauthorized use of Henrietta Lacks’ cells to create a polio vaccine and map the human genome, Black Americans have a documented history of being abused by the healthcare system.

“We get different kinds of treatment; oftentimes the treatment is rude or it’s insensitive,” Burrell said. “Sometimes folks just don’t want to be bothered with it all. We are a very resilient people and oftentimes we just suck it up until it gets to a point where we can’t bear it any longer.”

No Mercy

Raymond Ramsey was a San Francisco-based lawyer for two decades before he slipped into homelessness. An acrimonious divorce, the loss of his job and a mental health crisis formulated the perfect storm. He went from sleeping on friend’s couches to staying in hotels to living in his car. Eventually he ended up on the streets.

Ramsey, 54, says he’s alarmed and disheartened by the disproportionate number of Black homeless men and women dying in Santa Clara County.

Speaking from experience, he says the racist attitudes toward people of color are magnified even more when one is homeless.

“When you’re Black and you’re homeless it’s even worse, because [people think] you have something, you’re completely lazy, [or] you must have done something to deserve the situation that has happened to you,” he says. “People are less likely to help me on the street than they would my white counterparts at times.”

During the 10 years he lived on the streets, Ramsey says he was harassed by the police at least twice a week. At the time, he was on probation, which allowed the cops to search him without a warrant. He says they’d tear through his bag of personal belongs and scatter its contents across the sidewalk.

But for the last year-and-a-half, Ramsey and his wife have been housed at Second Street Studios: a 134-unit apartment complex for chronically homeless individuals. Referred to as permanent supportive housing, the first of its kind development in Santa Clara County opened in May 2019 and provides formerly homeless men and women with social services on top of a stable place to live.

For county leaders, this type of housing has become a key part of their plan to prevent homelessness. And studies show it works.

New research out of the University of California at San Francisco examined Santa Clara County’s Project Welcome Home program, which provides chronically homeless individuals with housing and supportive services.

From 2015 to 2019, 86 percent of participants received housing and remained stably housed during the course of the four year study.

During that same time period, the county—in conjunction with its non-profit partners—has housed 14,132 people, with 96 percent of them remaining in stable housing for at least 12 months, according to a report from Destination:Home.

But for every person who is housed in Santa Clara County, three more become homeless.

Raymond Ramsey was a San Francisco-based lawyer for two decades before he ended up on

the streets. He says racist attitudes toward homeless people of color contribute to the disproportionate number of Black homeless men and women dying in Santa Clara County. (Photo by Greg Ramar)

Speed of Need

Jennifer Loving, the CEO of Destination:Home, calls homelessness one of the most “pressing civil rights issues” in the Bay Area. In San Jose, 40 percent of households are considered low-income, meaning they make less than 80 percent of the area median income. That translates to less than $112,150 a year for a family of four.

But in recent years, San Jose has struggled to meet its state-mandated affordable housing goals. In 2019, San Jose issued 853 permits for all types of affordable housing compared to the 2,370 required by the state.

For extremely low income housing, the numbers are even more bleak, with San Jose issuing only 58 permits compared to the state’s goal of 525.

“Extremely low-income housing [is] the type of housing that I’m always advocating for,” Loving says. “You can see city-by-city, state-by-state how under-built that type of housing is in this country, which is why people can’t afford to live.”

Extremely low-income households make up 30 percent of the area median income, or $47,350 for a family of four in Santa Clara County.

In the San Jose, Santa Clara and Sunnyvale metro area there are only 34 extremely low income apartments available per every 100 renters, according to research from the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

But in Silicon Valley, building housing isn’t cheap. San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo says that one of the strategies to prevent homelessness is finding ways to cut through the bureaucratic red tape and build housing faster and at a more cost effective rate.

In light of the Covid-19 pandemic, Gov. Gavin Newsom in April temporarily suspended certain requirements under the California Environmental Quality Act, which under normal circumstances triggers project reviews that make it longer to build housing.

But with the emergency orders in place, it took the city of San Jose just four months to construct interim housing at Monterey and Bernal roads that will serve as transitional housing for 300 homeless residents.

“This has been an important opportunity for us to learn about how we can do this,” Liccardo said. “Now we simply need to scale these results, and obviously that’s going to take some legislative push, because when the emergency goes away, so do the emergency orders. We need to learn the lessons of this pandemic, which is if we’re able to move at the speed of the need we can actually get something done.”

San Jose Councilwoman Maya Esparza says that the city needs to “stem the bleeding” and do a better job at preventing homelessness through policy and protections. The Covid-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately impacted Black and Latino residents in Santa Clara County, has created a ticking time bomb for renters who are now at an increased risk of eviction and displacement.

“In making that correlation between who becomes homeless, we look at those that are going to be displaced,” Esparza said. “According to city statistics, 57 percent of the Black population is below 80 percent AMI, 56 percent of the Latino population is below 80 percent AMI, compared to 36 percent of the white population.”

With thousands living on the streets in Santa Clara County and thousands more at risk of becoming homeless, Ramsey has learned to find gratitude in the small things in life: a door he can lock at night, four walls and a roof over his head and the ability to take a shower daily. Over the last year-and-a-half, he says he’s had the chance to join mainstream society again and do things like visit the dentist or read the news.

The studio apartment that he and his wife live in only had a bed in it when they moved in last May. But over time, the space has become a furnished home with a kitchen set, a sofa and a television. Although small in size, Ramsey says that to him, it feels like a mansion. To this day he still finds himself overwhelmed at how his life has transformed.

“I wear my key kind of like a golden ticket around my neck right now,” he says. “[I’m] still rubbing it and saying, ‘Thank you Lord, I can’t believe I’ve fallen back into place.”

Woe is Josh

“Until relatively recently in our country’s history, Black Americans have been excluded from home ownership,” Dr. Kushel said.

Until relatively recently professionals of Dr. Kushel’s caliber sold elixirs from horse-pulled wagons and were barred from doing business on university property.

Until relatively recently Vietnamese people were excluded from home ownership in the Bay Area by 7500 sea miles, but remarkably they seem to have overcome that and every other imaginable hurdle.

Until relatively recently men like Josh Edwards lived in hobo villages and were rightfully ignored up until it was time to plant them in potter’s field.

> But as a Black man, Josh Edwards—

Who made Josh a “Black man”?

Is being a “Black man” a matter of choice, like gender?

Is Josh a “Black man” simply because he feels he wants to be a “Black man”?

If gender and being a “Black man” are both a matter of choice, can Rachel Dolezal be a “Black man”?

Who’s to say that Rachel ISN’T a “Black man”?

Racism the the new boogyman and whipping boy. Why has homelessness (using the article’s 13.79% pa growth) increased by 3.6 times in 10 years during a period of almost unparalleled prosperity and despite billions spent to “eliminate homelessness in 10 years” as public trough feeder Jennifer Loving has promised?

It appears Santa Clara County has become a homeless magnet since Mr. Ramsey relocated from SF. The CA Bar Association shows only one Raymond Ramsey – in Castro Valley. He was admitted to the bar in 1996 and suspended in 2013 for failing to provide family and child support. The suspension was lifted in 2013 and then reinstated. He remains ineligible to practice.

Presumably Mr. Ramsey could be a paralegal (~ $80K in SJ) or be otherwise productively employed. But blaming “structural racism” with its convenient, undetectable characteristics that defy corrective action is so much more convenient.

A bit more critical thinking, fact checking, and less sob sister reporting would be a refreshing improvement.

Emergency orders never go away, mister mayor. Just like temporary sales tax measures that we fools keep voting to extend when they’re about to expire because we’re told “your tax burden won’t increase; it stays the same”.

Mr Taxpayer! Thank you for your voice of reason! Racism is now the new cause of all social injustice! Life is about choices we make, regardless of the color of our skin! Society is now enabling this type of attitude that it is the color of our skin that matters most, not the choices and responsibility we all have. And this will just get worse, identity politics. Divide people according to gender, pronoun they identify with, color of skin, etc…

The media seems to be the source of divisions in our society. The more you make race the cause of ills in our society, the more you make people of color feel inferior. 75% of the homeless in California are from outside the State, they are given one way bus ticket when they are released from jail in other states.

Debbie, Thank you for your kind words though might be Ms. Taxpayer, not Mr. Taxpayer.

The article conveniently ignores the elephant in the room. Whites comprise the largest percentage of homeless – more than 2X that of Blacks. Are we to believe “structural racism” is responsible for their plight?

The 2019 homeless survey (Figure 12) https://www.sccgov.org/sites/osh/ContinuumofCare/ReportsandPublications/Documents/2015%20Santa%20Clara%20County%20Homeless%20Census%20and%20Survey/2019%20SCC%20Homeless%20Census%20and%20Survey%20Report.pdf shows the largest number (40%) of homeless are white and comprise 44% of SCC’s population.

Homeless Blacks are disproportionately represented @18% – i.e., 6X their 3% population percentage. Is racism responsible for a 29% increase in Black homelessness between 2017 and 2019?

Asian homeless are 3% – a bit less than 10% of their 36% population percentage i.e, inline with Phu Tan Elli’s observation. Is reverse “structural racism” responsible for the low percentage of Asian homeless?

Is “structural sexual orientation discrimination” responsible for the almost 2X increase in gay and lesbian homelessness in the same period?

The more one looks at the data, the less credible the article becomes.

> Racism is now the new cause of all social injustice!

Just the opposite: “racism” is not new, it’s very, very old. “Racism”, aka “tribalism”, has been the defining social ethos of humans since the dawn of the species.

It was The Enlightenment and the evolution of western civilization that challenged humanity to evolve beyond tribalism.

Collectivism, identity politics, socialism, Marxism, communism, and “wokeness” are just efforts to reject the Enlightenment and “turn back the clock”

Our formerly “great” universities are joining in the lemming march to “wokeness” oblivious to the fact that it completely delegitimizes the whole point of universities which arose out of the Enlightenment.

This is simple Mr. Taxpayer,

No need to get all worked up over progressive, structural, systemic, racism.

This simple adage explains it all.

Figures don’t lie, but liar’s do figure.!

Thank you so much for this insightful article. I work in healthcare and the evidence for racial disparities in the provision of healthcare are overwhelming, thus outcome disparities exist as well. There are also very well documented disparities in the legal system, a Black or Latino person is more likely to be incarcerated than a white person for the same crime committed. We could go on, but all of these do add up and make homelessness more frequent for BiPOC folks. Yes, our choices can matter, but the systems we have set up and blindly accept also matter a lot and need our attention if we want to solve homelessness. Check out this website for more information on systemic racism in our criminal justice system: http://www.sentencingproject.org

Uncle Al, Here again a closer examination of the data doesn’t support the cruel society thesis. But it may explain why journalism has ceased to be a trusted, respected profession.

Is “structural racism” responsible for verdicts by predominantly BiPOC juries? Or sentences imposed by Black justices? It been extensively studied and [drum roll] *not* supported by objective research. Do keep in mind that “correlation does not imply causality”.

Is “structural racism” responsible for the ~53% of *all* US gun homicides committed by 13% of our population? And the vast majority of the victims are also Black.

Is “structural racism” responsible for the enormous gains in economic prosperity among Blacks since the passage of the civil rights act?

Contrast the improvement against feeble gains in predominantly Black countries like Haiti and virtually all Black African countries. Or the economic reversal where Whites fled after persecution such as Zimbabwe?

I suspect racism (as popularly used) remains present at some level. Affinity behavior seems a biological trait. But blaming racism for all outcomes would be risible were it not a tragic example of gullibility.

It is not all or nothing. You are trying to set up a binary choice, but I am happy to see you do reluctantly acknowledge that, yes, some racism exists. You are hand picking and then sharing data that fits your narrative. Keep looking at the data and you will see we have some work to in order to achieve a more equal society. I know we can do it.

> There are also very well documented disparities in the legal system, a Black or Latino person is more likely to be incarcerated than a white person for the same crime committed.

So much progressive ignorance and muddle thinking can be traced back to language ambiguity or imprecision.

Here Uncle Al thinks there are sentencing disparities for “the same crime”.

No. It’s NOT the same crime. It was a DIFFERENT crime. Committed by different people at a different time and place with a different victim.

Maybe the CHARGE was the same or similar. But the facts were DIFFERENT.

We want a justice system based on actual facts. NOT a justice system based on identity politics.

The City of San Jose would have more affordable housing if the business backed city council members (Liccardo, Diep, Khamish, Foley, Davis and Jones) didn’t continue to allow developers to not build affordable housing in their projects. These City Council members are supported in election/ reelection campaigns by these developers in campaign contributions. That is the reason why this mayor and city council continue to waive fees for developers. Follow the money. You can change this by not reelecting Lan Diep in District 4 and Dev Davis in District 6.

Stop using drugs.

All posters (except Uncle Al) I am honored and humbled to be in your presence.

So Uncle Al, you would like to have incarceration’s by quota? Do we let more of the bad guys go or throw more good guys in? How’s that work? Do we just randomly pick different colored people charge them with a crime, and see if they can buy a lawyer and get out? If they do we can charge them with being racist.

Uncle Al, I *do* look at data. Lots of it – and from a variety of sources including psych journals, economic research, legal journals, and crime statistics. I also know a bit about statistics and scientific methodology e.g., 2 University of Chicago grad students cited my work in their Human Development Ph.D. theses.

The “binary thinking”, “all or nothing” accusation aka False Dichotomy is one of ~ 15 classical logic flaws. Citing data that fails to support one theory doesn’t imply that the obverse is correct.

If “hand picking” data, then please provide credible data to support your theory. Keep in mind the definition of gaslighting, “Gaslighters — people who try to control others through manipulation — will often accuse you of behaviors that they are engaged in themselves. This is a classic manipulation tactic.” Et tu Brute?

I don’t doubt that racism exists. The latest (2019) FBI UCR report shows Blacks committing hate crimes 2.2X that of Whites when normalized by population. And completely concur that we should strive to provide equal opportunity and a safer, more peaceful society.

However, how much is racism a factor in outcomes, what corrective action is warranted, and what difference will corrective action make? Am eagerly awaiting your data sources.

> By Grace Hase

Sounds like Grace has been sheep dipped in postmodernism/Social Justice Activism.

James Lindsay (“Cynical Theories”) says Social Justice Activism is not the same as social justice activism.

Maybe instead of constructing Social Justice narratives, Grace could just give us all the direct sales pitch on postmodernism, we could give it a thumbs up or thumbs down, and then get back to journalism.

The comments here give me hope for our society. It’s been very rare to see such a rational discussion of facts. Thank you everyone, except for Uncle Al.