The year 1918 was marked by death and destruction on a scale never recorded before in human history. World War I—the “war to end all wars,” as it was tragically dubbed—wrought havoc across Europe and left a ghostly wasteland of roughly 40 million soldiers and civilians in its wake. Probably twice that many were seriously wounded or deformed. The fighting in the trenches of France, Belgium and Germany had been particularly gruesome, leaving an entire generation scarred and haunted by its terrors.

On the heels of this apocalyptic bloodshed came an even more deadly and invisible executioner in the form of an influenza pandemic—which today is known incorrectly as the “Spanish Flu”—that was to claim as many as 100 million lives during a trio of outbreaks that circled the far corners of the globe over a period of roughly two years.

The first wave of the global influenza pandemic hit the United States in March of 1918, when soldiers stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, broke out with flu-like symptoms before being sent to Europe to fight in the war.

And while no one is certain about where the influenza originated (although Spain took a bad rap largely because it remained neutral during the war and had an open press reporting on outbreaks), it was certainly an H1N1 virus of avian origin.

Some believe that the disease mutated in Europe, turning virulent and deadly, and soon there was a massive outbreak during the spring of 1918 among troops and civilians alike living in the mud, blood and grime.

The virus returned to Boston in April, then back to Kansas in mid-summer, traveling along transit corridors, until by Sept. 24, headlines in the San Jose Mercury Herald declared: “INFLUENZA RAGES IN CAMPS.” At Camp Devens in Massachusetts, 8,000 young men were said to be stricken with the virus; 65 had died in a single day.

In spite of the apparent virulence of the illness, no one was prepared for a West Coast swing. Influenza was not made a reportable disease in California until Sept. 27—only after the illness had already reached the state.

During September’s final week, state newspapers noted that there were more than tens of thousands of new cases of influenza being reported in U.S. military installations across the country, and that the first cases in California had been reported in Camp Kearny, in San Diego County, 10 miles inland from La Jolla.

The virus, following highways and rail lines, quickly spread northward—San Pedro, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, San Jose, San Francisco, Sacramento, Redding, Eureka. By mid-October, there were 6,092 cases reported in the state.

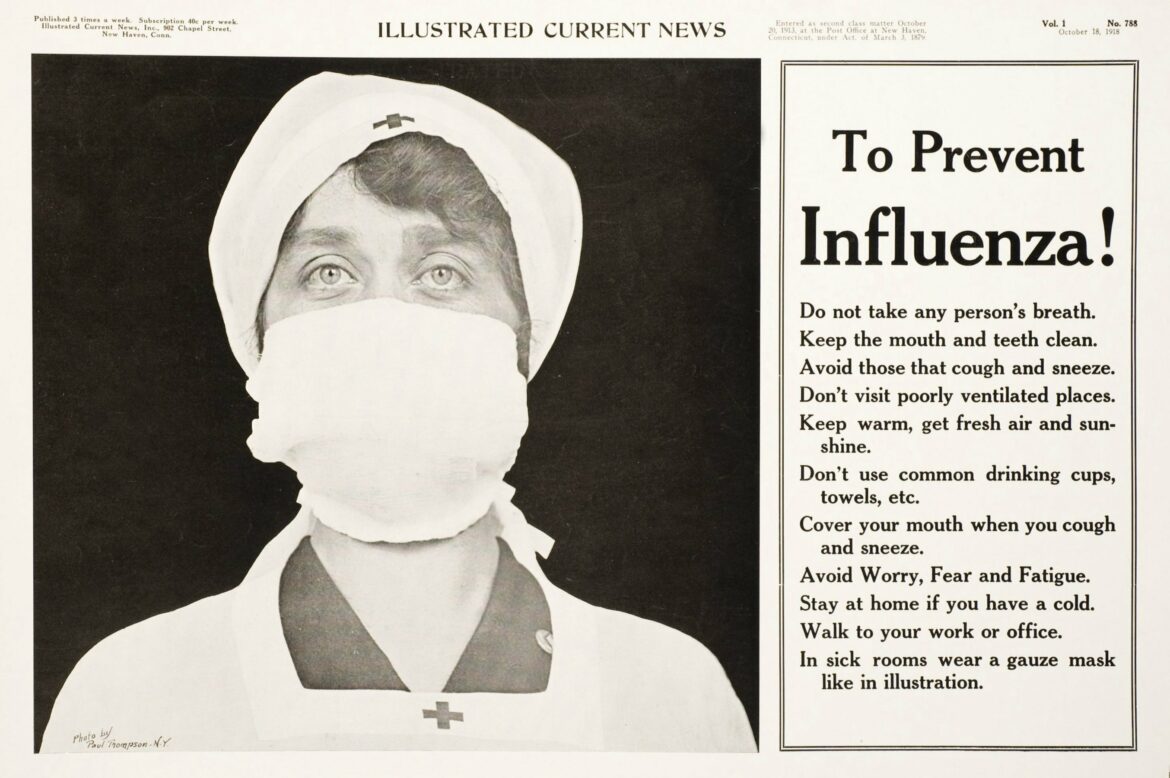

A public health ad that ran in local papers during the 1918 flu pandemic.

Viral Spread

Like today, government officials and media did their best to minimize the impact of the illness and its rapid spread. On Sept. 25, 1918, The Mercury Herald acknowledged that “the Spanish influenza, according to the dispatches, has reached the Pacific coast,” but the newspaper felt compelled to add that “this need not particularly alarm anyone” and posited that “the Government is dealing successfully with it.” Rest and relaxation, the paper declared assuringly, were “effective” remedies against the illness.

As late as Oct. 5, Santa Clara County’s “health officer,” Dr. William Simpson, publicly countered a rumor that there were cases of Spanish influenza in the region. This was simply not true. There were numerous cases and deaths reported throughout the Bay Area by then, and four days later, it was reported that more than 150 cases had broken out at Camp Fremont, a military training installation on the county’s northern edge.

The following day, despite headlines proclaiming “EPIDEMIC DANGER IN [CAMP] FREMONT IS PASSING,” the count of cases had jumped to 184. A few days later, the number had skyrocketed to 405. Col. Asa L. Singleton, chief of staff at the camp, optimistically declared that the camp’s quarantine “will be lifted … within ten days.” It would not be. That same day, 150 new cases were reported at nearby Stanford University, and 60 in Palo Alto.

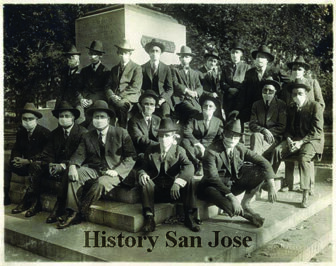

Because of the the flu epidemic, groups were forbidden from meeting indoors, prompting the Native Sons of the Golden West to mask up and conduct gatherings in San Jose’s St. James Park.

Few people today are aware that the U.S. Army had a massive training camp consisting of more than 7,200 acres and 1,200 buildings straddling the El Camino Real, on what is now land included as part of the Stanford campus, downtown Menlo Park and East Palo Alto.

At its peak, it served as home to the 8th Infantry Division, consisting of 27,000 troops, along with 10,000 horses, mules and cattle.

In the fall of 1918, U.S. Army medical staff at Camp Fremont was clearly unprepared for the pandemic’s onslaught.

On Saturday, Oct. 19, a letter written by a trainee at Camp Fremont stricken with the illness was made public. The missive, sent to a woman living in San Jose, found its way to the hands of a reporter. The letter described the “shortage of nurses at the base hospital” and urged the recipient of his letter, a “Mrs. L. Richards,” to “appeal to the women [of the community] to volunteer as aides in the present emergency of the camp.” He described the situation as “desperate.” He said that the nurses presently at the camp were “overworked” and that “patients cannot get the attention they require.” He estimated that “more than half of the regular army nurses are incapacitated from the work.”

Case Count

San Jose officials were still trying to downplay the problem’s severity.

An article in the San Francisco Chronicle appeared with a headline declaring “CALIFORNIA FLU CASES 19,000,” although the paper claimed “the influenza epidemic in [San Jose] is slowly subsiding. … Most cases reported today were from families already having a case reported.”

In San Jose proper, the impact of the influenza could no longer be swept under the rug by county officials or the regional newspapers. In its Sunday edition of Oct. 13, the San Francisco Examiner printed headlines reading: “4 BROTHERS VICTIMS OF PNEUMONIA—French family in San Jose Almost Wiped Out by Influenza in Few Days; 127 New Cases There.”

The paper reported that “three sons of Mary [Marie] Loustelet, residing at 445 W. San Fernando Street are dead, and a fourth is at the point of death in the County Hospital as a result of the influenza epidemic in this city. A fifth son, Jean [his name was actually Eugene], is battling with the French troops on the Western Front.”

While the Examiner butchered the family’s history—it wrote that the Loustelets had immigrated from France a few years ago, when in fact they had first come to the Santa Clara Valley in the 1890s, the Examiner account accurately reported the horror inside their household.

Numerous cases of the flu broke out in fall of 1918 at Camp Fremont, a major military training base that now spans part of Menlo Park and Stanford University. (Photo via History San Jose)

The Loustelet family, the paper noted, had created a “happy home” just south of the Alameda near the Guadalupe River. In March of 1918, the Loustelet father, Joseph, who worked as a laborer, had “died suddenly” at the age of 57, although the cause of death was unknown.

During the preceding week, the Loustelet’s youngest son, Leon, aged 6, had died from pneumonia, following a battle with the influenza; then a few days later, their 21-year-old son, Emil, died of similar causes. The two brothers were buried side by side. Then, on Saturday night, the newspaper account asserted, another son, Joseph Jr., 17, died at the county hospital.

According to the Examiner, Marie Loustelet awaited “broken hearted” at the bedside of her fifth son, age unknown, in the hospital. At press time he was still alive, though he apparently died as well. By then, the number of new cases in San Jose had jumped to 127, bringing the total to 430.

At one point, during the height of the pandemic, San Jose’s Dr. George W. Fowler, an 1892 graduate of Santa Clara College, forerunner of Santa Clara University, reportedly attended to 525 patients in a single day.

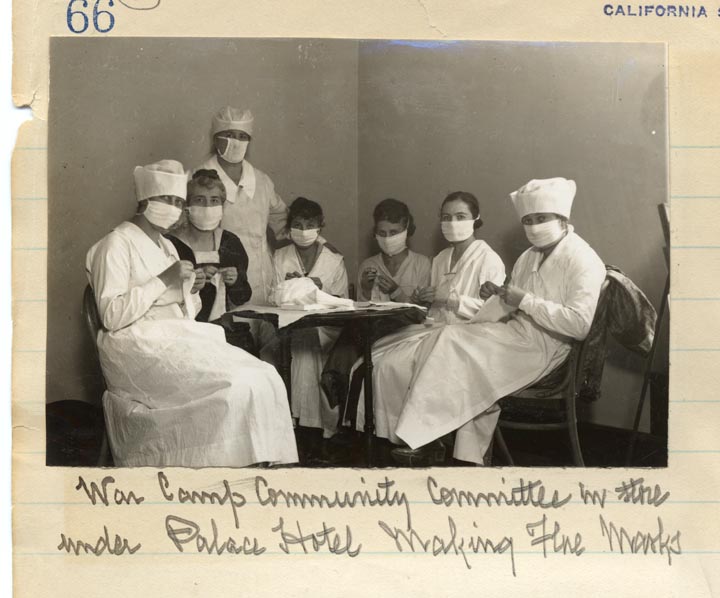

Indeed, as the number of cases exploded, hospitals became so overcrowded that makeshift medical centers were established throughout the region. In San Jose, portions of the San Jose Normal School—then a teacher’s college and today San Jose State University—were used as hospital wards. Industrial Arts Magazine of 1919 contained an extensive account of the “urgent” situation in San Jose when the pandemic hit.

In an article entitled “How a City and a School Met the Epidemic,” written by Charlotte Morton, then head of the Household Arts Department at the Normal School, Morton explained how those in serious condition remained in the county hospital, but those who were in recovery were moved to the makeshift medical stations to make room for those in need of critical care. A single “young” doctor and some 75 volunteers staffed the facility. All of the food and requisite equipment were donated by the community.

“The response was thrilling,” Morton wrote. “It was a lesson in the fundamental goodness of human nature. The people can be trusted! When a call comes, how nobly they respond; to what heights of self-sacrifice and depth of self-denial they will go!”

Flu Survivor

Almost instantaneously, the numbers and statistics appearing in the local newspapers were replaced by deadly accounts involving family, friends, neighbors and community figures. That which was previously abstract had been replaced by flesh and blood.

My mother’s family from Northern Italy had immigrated to San Francisco, San Jose and Santa Cruz during the turn of the 19th Century. My mother was born in Santa Cruz in the spring of 1915, the fifth of 13 children born to my grandmother, Batastina Loero Stagnaro. Our cousins, the Vincent Zolezzi family, resided in San Jose.

Sometime during the late 1970s, my mother, Iolanda “Lindy” Stagnaro [Dunn], contracted a severe case of influenza and had a temperature approaching 103°F, along with tremendous body aches and pain. I remember being frightened, as I cared for her, by the seeming virulence of the illness.

“Don’t worry,” she assured me. “I survived the Spanish flu when I was a girl, and I will survive this.”

That was the first time I had ever heard her talk about her experience with the influenza as a child. The distance between history and the present had vanished in a fearful instant.

My mother would casually mention surviving the “Spanish flu” from time to time after that, and several years ago, while doing research in the archives of local newspapers, I came across an account in the Santa Cruz Evening News from the autumn of 1918.

“The influenza is very prevalent among the [Italian] fishermen, where in several cases, the entire families are ill,” the newspaper reported. “Nearly all of the patients reside on Lighthouse Avenue, Laguna and Gharkey streets,” the city’s Italian neighborhoods. “Cottardo Stagnaro [my grandfather] of the Stagnaro fishing company, his wife [my grandmother] and four children [my mother, my aunts and an uncle] are all ill, five members of the Olivieri family, two children of Steve Stagnaro, a son in the Bassano family, Mrs. Clara Ghio [my great aunt], Mrs. Catharina Castagnola and others.”

They were all cousins or married into each other’s families, one way or the other, and I knew and loved them all in my Baby-Boomer youth nearly a half-century later.

My mother showed me a picture in her scrapbook of her aunt (and my great aunt),“the Mrs. Clara Ghio” identified in the article, in a mask, my mother told me, that she was required to wear in Santa Cruz during the 1918-19 pandemic.

It was a stunning, memorable image. The photograph, taken in a studio, shows my aunt wearing stylish dress and an equally stylish hat, adorned with a chrysanthemum. Her strong rough hands reveal a life of working in canneries, tending to her garden and mending fishing nets. And her eyes, highlighted by the mask, stare directly into the moment and the catastrophe at hand.

Several facilities throughout the region were converted into makeshift hospitals. (Photo via HIstory San Jose)

Masks On

After a general public paralysis throughout the state, communities began closing schools and put a halt to various forms of public congregation, in theaters, amusement parks, movie houses, indoor sporting events and churches. Indoor meetings were prohibited. These restrictions, as today, were hotly contested.

The second form of public response to the pandemic was, as today, equally controversial—the wearing of gauze masks while in public. “Those who wear [masks],” the Mercury Herald opined, “will be 99 percent safe.” A Red Cross public service announcement stated bluntly, “the man or woman or child who will not wear a mask now is a dangerous slacker,” calling into question the patriotism of those who refused.

The United States Treasury Department issued signs throughout California proclaiming “Influenza Spread by Droplets Sprayed from Nose and Throat.” The notices contained the following directives:

- Cover each COUGH and SNEEZE with handkerchief.

- Spread by contact.

- AVOID CROWDS.

- Do not spit on floor or sidewalk.

- If possible, WALK TO WORK.

- Do not use common drinking cups and common towels.

- Avoid excessive fatigue.

- If taken ill, go to bed and send for a doctor.

- The above applies also to colds, bronchitis, pneumonia, and tuberculosis.

Similar directives appeared in virtually all regional newspapers.

Proposed remedies for the 1918 influenza were many and often byzantine. Everything from placing an onion on the bedpost, to sprinkling Indian tobacco on a victim’s chest and pointing the left index finger at the moon were promoted as providing a cure. Eucalyptus oil, whisky, camphor, castor oil, quinine, cayenne pepper (followed by a liberal dose of laxative) and more were advanced as elixirs. Bayer’s Massage Parlor at 85th S. First St. in downtown San Jose placed ads in newspapers proclaiming its services as a “Guarantee to Cure Spanish Influenza.”

One reporter condemned the remedies as being based on “home treatment, witchcraft and voodism”—although no one, it should be duly noted, had gone so far as to suggest the injection of Lysol or other disinfectants during the 1918-19 pandemic.

New Wave

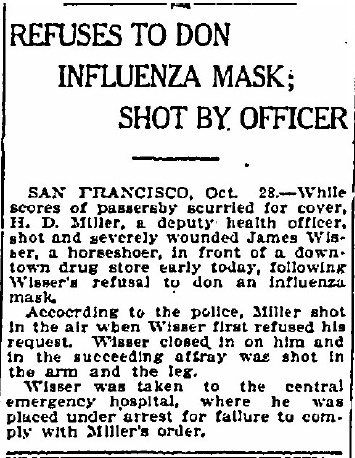

Many arrests and confrontations erupted involving mask compliance during the 1918 pandemic.

By the second week of November 1918, it was clear that the War in Europe was nearly over and that Germany was preparing to surrender.

But the war against the influenza continued.

Advertisements appearing in local papers declared that District Attorney George W. Smith was prepared to prosecute those who failed to wear “the required influenza gauze masks.” Several arrests were made throughout the Bay Area.

In late October, H.D. Miller, a deputy health officer in San Francisco, shot and severely wounded James Wisser, a horseshoer, for failing to wear an influenza mask. An Anti-Mask League later formed in the city, drawing up to 2,000 supporters.

On Nov. 6, it was reported that “110 non-maskers [in San Jose] have suffered arrest for violation of the mask ordinance which was passed by the Council a week ago.” They were fined $5 each, which was then donated to the Red Cross.

By the first week in November, however, the Great War had recaptured the nation’s attention. On Monday, Nov. 11, banner headlines throughout California trumpeted “HUNS QUIT!” and “WAR ENDS!” with subheadlines declaring that “Germans Sign Armistice at 5 O’clock” and “Hostilities Cease at 11.”

Trucks from San Francisco carried special editions of various newspapers “down the peninsula highway” bearing “the momentous tidings to the waiting throngs in San Jose, Morgan Hill, Gilroy, Hollister … and every other town in between. In all cities visited the allied victory was being celebrated by feverishly excited and joyous multitudes.”

Thousands flocked to downtown San Jose, where in a matter of four hours, a “Liberty Day Peace Parade,” was assembled, with a large group of women dressed in white carrying an American flag down First Street.

But the battle against influenza waged on.

On New Year’ Eve of 1918, the San Jose Mercury News reported: “The conditions for San Jose and adjoining territory seem to be on a direct road to improvement as far as influenza is concerned. … At all the local hospitals, the conditions were reported as better, nearly all those ill were doing nicely and the percentage of new cases had dropped to a very small number.”

The very next day, however, Jan. 1, 1919, the paper carried headlines declaring: “Influenza Epidemic Takes Turn for Worse. … 38 Cases Reported.” Dr. James Bullitt, San Jose’s health officer warned “that the number of pneumonia cases developing each day is on the increase.” A third wave of the influenza had hit Central California, causing more illness and more deaths until the beginning of spring.

Thousands of onlookers flocked to the heart of San Jose for a “Liberty Day Peace Parade” celebrating the end of WWI. But the battle against influenza raged on. (Photo via History San Jose)

Paper Trail

As I read through the papers of local newspapers from a century ago garnering this historical record, I was startled by how many names I recognized and how many people I actually knew while growing up as a kid in the region many decades later.

I hadn’t realized that my mom’s entire family—and so many in the Italian fishing community in Santa Cruz that had nourished me when I was young—had been stricken with the influenza. How my life would have been irrevocably altered had they died.

My great aunt Clara was a special favorite of mine and I loved hanging out with her in her backyard wine cellar while she sorted through fava beans. She lived to be 68.

Her husband, my great uncle Cottardo “Trub” Ghio, had fought in France during World War I and lived to be 92.

Clara Ghio, the author’s great aunt, lived in Santa Cruz during the 1918 so called Spanish Flu pandemic.

My mother, who would outlive the pandemic by nearly a century (she died at the age of 99 in 2014), had a survivor’s attitude for most of her life. She was tough and feisty and determined until the end.

The Great Pandemic of 1918 was simply her first of many hills to climb, and it gave her a sense of confidence that she could survive others.

In San Jose, I was able to track down the life of the last surviving Loustelet son, Eugene, who had fought in France and had returned to San Jose after the war, where he found that his family had been decimated by the influenza. In 1926, he and his “broken hearted” mother, Marie, lived together in East San Jose; he was working as a mechanic.

The 1930 U.S. Census has him living in a dormitory at St. Joseph College Seminary in Mountain View and working as a janitor. By then, the trail of his mother stopped. I found copies of both Eugene’s World War I & II draft registration cards. He was 46 at the time of filling out the latter, in 1942, and his hair by then had turned grey. He apparently died in 1956, in Kern County.

Life goes on, as we know. And then it doesn’t.

Nietzsche was right: That which doesn’t kill us makes us stronger. Human communities have survived wave after wave of pandemics for millennia. History reminds us that life is a bit of a crap game. We will mostly get through this current pandemic, but, unfortunately, not all of us.

It’s a sobering thought. For better or worse, that is the nature of the beast.

Great HISTORY..

Great article!

Here are the lyrics of a song, sang by children during the inflenzaa pandemic…if my memory serves me correctly…

“I had a little bird, its’ name was enza…I opened the window and in..flu..enza.”

Check Valley Medical Center (VMC) for the “potter’s field” which was discovered when constructing a new wing at the hospital…rumor has it these graves were “flu” victims..

David S. Wall

…and in flow enza…

Ha! That’s a good one.

And yeah, that WAS a good article.

> [World War I] left a ghostly wasteland of roughly 40 million soldiers and civilians in its wake. Probably twice that many were seriously wounded or deformed.

40 million?

Wikipedia seems to put the number of military and civilian dead at less than 18 million.

Spanish flu?

> which today is known incorrectly as the “Spanish Flu”—

Incorrectly?

It’s known as what it’s known as: “Spanish Flu”. Wikipedia says:

> The Spanish flu, also known as the 1918 flu pandemic, was an unusually deadly influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. Lasting from spring 1918 through spring or early summer 1919, it infected 500 million people – about a third of the world’s population at the time.[2] The death toll is estimated to have been anywhere from 17 million to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in human history.[

It’s bad enough that we are constantly subjected to exaggerated “worst case scenarios” for coronavirus, but the constant distortion and revision of the historical record makes it almost impossible and hopeless to ever know anything for certain.

Total racism label for a flu.. Im disappointed

When you snowflakes can’t think of anything intelligent to say, you spit out “racism”.

Nancy Pelosi should have never suggested to inject Lysol into your lungs.

Thank you for sharing this history and your family’s spunky survival of the 1918 flu pandemic. It is in lightning to read about both the similarities and the differences between 1918 and 2020.