Rob and Mialisa Bonta describe themselves as partners in life and partners in service. Together since they were 17-year-old freshmen at Yale, the Democratic assemblyman and his wife, an Alameda school board member, have long shared an ambition to provide young people with educational opportunities.

And so, while she led nonprofits that promote children’s literacy and he was in his third term in the Legislature, Rob Bonta in 2017 created a foundation to support community programs and give scholarships to needy students. The Bonta California Progress Foundation is one of a growing number of nonprofits launched by California state lawmakers in the last decade.

It’s unusual not only because it’s affiliated with a single legislator, rather than a caucus, but also because of whom it has benefited, besides needy students: the organization that, at the time, employed Bonta’s wife.

In one of its first acts of charity in 2018, the assemblyman’s foundation gave $25,000 to Literacy Lab, a nonprofit where Mialisa Bonta at the time was earning a six-figure salary as CEO. The arrangement—which the Bontas say is consistent with their other philanthropy—appears to be legal, according to experts in federal tax law and California’s political ethics law.

But governmental watchdogs and the state law’s author say it also reveals a regulatory gap that invites conflicts of interest.

“This should not be allowed, and the law should be amended to prohibit it,” said Bob Stern, who was the principal co-author of California’s Political Reform Act, the landmark 1974 law that amounts to the state’s tool for preventing corruption.

“The reason there is nothing against it is because … you can’t anticipate everything. You can’t anticipate that he would take advantage of the law the way he is.”

Filings with the Fair Political Practices Commission show that after launching his foundation, Bonta solicited donations from interest groups that lobby him at the Capitol—including PG&E, the teachers union, and the maker of Budweiser beer. They pumped $75,000 into the Bonta California Progress Foundation during 2017 and 2018, according to filings with the state’s Fair Political Practices Commission.

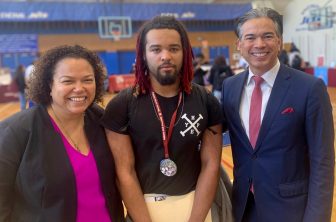

Mialisa and Rob Bonta flank a student at a college fair sponsored by the assemblyman’s nonprofit. (Photo courtesy of Rob Bonta)

From that pool of donations, tax returns show, the assemblyman’s foundation in 2018 gave $2,500 to a metal arts studio in Oakland and $25,000 in 2018 to Literacy Lab, his wife’s group.

“We’re working on areas of shared passion, in my district, with my constituents,” Bonta said. “So they’re perfect opportunities to partner and support one another with the common goal of helping the same communities and folks that we care about.”

The $25,000 to Literacy Lab was a loan, Bonta said, though that’s not reflected in his foundation’s tax return. After questions from CalMatters, Bonta said he intends to file a corrected tax return with the IRS.

Mialisa Bonta said the loan helped her start-up nonprofit get off the ground as it began distributing e-books to low-income families.

“In the world of (education) tech financing, it’s very common for the organizations to be capitalized either through direct contributions or loans,” she said. “And that is simply what that transaction was about.”

It wasn’t the first time Rob Bonta had directed money to Mialisa Bonta’s employer. He donated $2,000 from his campaign funds to a nonprofit called Bring Me a Book when his wife was the executive director there in 2013. Records show he donated $21,000 from his campaign account to Literacy Lab between 2015 and 2019, when she was its CEO. And, just last month, Bonta donated $4,500 from his campaign account to Oakland Promise, the nonprofit Mialisa Bonta joined last year.

In making those donations, Bonta obtained letters from Literacy Lab and Oakland Promise stating that his contributions would not be spent on his wife’s salary or benefits. State law prohibits politicians from using campaign funds for personal benefit, including donations to charities if they’re used toward a spouse’s salary.

His donations to her organizations are in keeping with his pattern of supporting community-based groups in his region, records show, and amount to a sliver—about 16 percent—of the more than $175,000 in civic donations Bonta has made from his campaign accounts over the last eight years.

He’s also helped his wife’s organizations by asking donors to give them money, or facilitating her fundraising efforts. Between 2014 and 2016, state disclosures show, Bonta solicited $517,500 from donors including Google, PG&E and the owner of an Oakland cannabis dispensary to support his wife’s nonprofits. The bulk of it—$500,000—was in the form of a grant from Google to Bring Me a Book, where Mialisa Bonta worked before joining Literacy Lab. The rest were smaller donations to Literacy Lab.

This year, Bonta helped raise $20,000 for Oakland Promise, where she is now CEO. Recently, he obtained letters saying the funds will not go toward her salary.

Solicitations like this are known as a “behested payments” under California’s political ethics law—money a donor gives to a charity at a politician’s request. It’s one of the less restricted ways for donors to curry favor with politicians. Unlike donations to political campaigns—which are capped at $4,700 for legislative candidates—there is no limit on the amount donors can give to charitable groups at a politician’s behest.

Bonta has behested donations to many charitable groups, not only those tied to his wife. He said he had little role in helping his wife’s employer land the Google grant, which was awarded through a competitive process that involved a selection committee and a public vote through social media. Bring Me a Book, he said, “had to fight for it and earn it.”

But because Bonta wrote a letter of recommendation to the selection committee supporting Bring Me a Book’s application, he said he reported the Google grant as a behest out of an abundance of caution.

The Fair Political Practices Commission wouldn’t say definitively if such a situation requires public disclosure as a behest. The law requires reporting behested payments when they are made “at the request, suggestion, or solicitation of” an elected official.

“We always recommend to err on the side of caution and report a behest if there is any question as to whether it is or isn’t,” FPPC spokesman Jay Wierenga said in an email.

Mialisa Bonta said her husband played a minimal role in some other donations he reported as behested payments. In some cases, she said, he just introduced her to someone at a social event and then she followed up later with a fundraising pitch.

“There are many, many steps between sitting next to somebody at the dinner table and any kind of funding that would come directly to one organization,” she said.

California’s requirement that these kinds of interactions be disclosed as behested payments promotes transparency in state government, said Jessica Levinson, a professor at Loyola Law School and former president of the Los Angeles Ethics Commission.

“More information is better,” she said. “Knowing what our officials are doing, who they’re talking to, who they’re asking for money from and for what purposes, is beneficial.”

Whether officials make a loan through their own nonprofit or ask donors to directly give to an organization, “the law should say you cannot solicit money to go to a nonprofit that employs your (spouse),” said Stern, who helped write California’s political ethics law.

And, he said, the prohibition should also extend to a politician’s campaign account: “Anything he controls he shouldn’t use to send money to something that she controls.”

The Bontas said the family’s income does not benefit from the assemblyman’s solicitations. “Her salary doesn’t change based on these behests or loans, it’s set by an independent board,” he said. “It’s not connected.”

Tax filings for 2019 are not yet available, but Bonta said that in the last year, his foundation has given $26,000 in college scholarships to 16 students and sponsored a college fair at a high school in his district that handed out more scholarships and helped 47 students get admitted to historically black colleges and universities. These activities, Bonta said, are “opening doors of opportunity and transforming lives.”

Bonta also isn’t the only politician soliciting donations to his spouse’s charity.

Secretary of State Alex Padilla has reported raising $535,000 in the last year for FundaMental Change, a nonprofit his wife Angela Padilla founded in 2017 to promote mental health. But she is not paid by the organization, according to the group’s lawyer, Stephen Kaufman.

Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez raised $37,500 in 2016 and 2017 for a charity her husband Nathan Fletcher launched to help veterans cope with depression and prevent suicide. It merged with a larger veterans charity before any significant tax filings became public, but issued a financial report saying Fletcher was not compensated.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s wife Jennifer Siebel Newsom has, for many years, run the nonprofit Representation Project that makes media about gender stereotypes, but she, too, is unsalaried. She recently announced she is launching a new nonprofit focused on gender and children’s issues, and will not be paid by it either, her spokesperson said. Donations to the new California Partners Project will be reported as behests by the governor’s office, said executive director Olivia Morgan.

The governor has not yet reported behesting any money to his wife’s organizations, though critics of political behesting point out that he almost doesn’t need to formally ask donors for charitable contributions. Any moneyed interest that wants to please Newsom will know that supporting his wife’s causes is one way to make a positive impression.

Eric Gorovitz, a lawyer who specializes in nonprofits for the Adler & Colvin law firm in San Francisco, said there’s nothing in the law that prevents a politician from encouraging people to support their spouse’s organization, or even from using their own nonprofit to transfer money to another nonprofit that employs their spouse.

“There is no issue under the tax code,” Gorovitz said. “It is perfectly legitimate to say, ‘My husband is doing this great stuff, you should give him some money.’”

But, he acknowledged, the goal of federal laws governing nonprofits—which is focused on tax collection—is different from the goal of California’s political ethics law, which aims to prevent corruption by disclosing influential transactions. “It’s a really different purpose,” Gorovitz said. “And they often come together, but they often don’t.”

CalMatters is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining policies and politics.

https://calmatters.org/projects/state-investigates-evan-low-tech-foundation-calmatters-report/

In California, lawmakers frequently champion charitable causes, yet critics argue that their actions sometimes benefit their own constituencies disproportionately. The state’s legislative landscape reveals a pattern where charity and support often seem to be directed toward areas that are politically advantageous or personally beneficial to the lawmakers themselves. This dynamic raises questions about the genuine intent behind such charitable endeavors and whether they truly serve the broader public interest. For example, when considering financial assistance programs like SASSA approval lookup, transparency in how resources are allocated becomes crucial to ensure that aid reaches those who need it most, rather than being swayed by political influences.