San Jose voters passed Measure B in 2012 with the promise of saving $68 million a year by slashing healthcare, disability and pension benefits for city workers. At the time, unfunded liabilities gobbled up a quarter of the city’s annual $1.1 billion budget while declining tax revenues prompted painful cuts to staffing and vital public services.

Then-mayor Chuck Reed championed the initiative as a way to stave off financial ruin.

Unions successfully challenged the legality of several Measure B provisions, forcing a compromise in 2016 that lowered projected annual savings to $42 million. Reed, who termed out in 2014, applauded the truce and continued preaching the gospel of Measure B as a national model for reform.

That singular focus on employee benefits overlooked what’s become a major driver of the pension crisis: risky bets with high fees and poor returns.

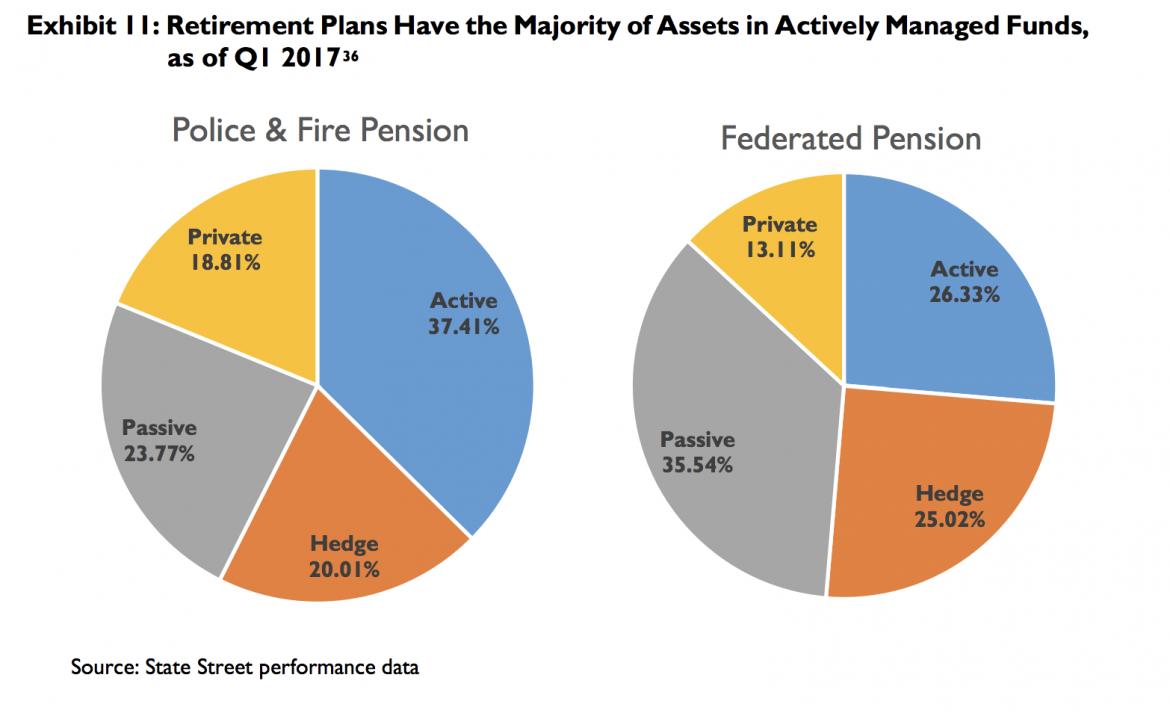

In the decade from 2006, San Jose’s two pensions—the $2.1 billion Federated City Employees System and $3.5 billion Police and Fire Plan—upped allocations to alternative investments from 6 percent to 43 percent and 9 percent to 48 percent, respectively.

San Jose now pays its Office of Retirement Services $75 million-plus a year to administer the plans. That includes $1 million in legal expenses and $2.75 million for consultants who steer the plans toward investments which rack up $60 million in fees. By 2017, those investment fees alone rose another 16 percent to $70 million.

It’s a cost that soared by more than 150 percent in a decade and now significantly surpasses the savings promised by Measure B reforms. It’s as much as a 1984 bond loss by a San Jose finance official that went down as one of the worst local decisions of the last half-century. Effectively, it’s a transfer of wealth from workers to Wall Street.

Fund and Games

Traditional index and mutual funds, stocks, bonds and cash rise and fall with the economy. Alternatives include a vast range of assets—land, art, coins, derivatives contracts—and occupy a shadowy part of the financial universe where money managers make bets in exchange for an upfront fee and a chunk of the profits if the wager pays off.

But San Jose never saw a full accounting of those fees and incentives payouts until 2016, when retirement services staff began making yearly reports disclosing indirect expenses. In prior years, they obscured the true costs from the public by deducting fees and performance payouts from investment income or net returns.

Source: City of San Jose

Edward “Ted” Siedle—a former US Securities and Exchange Commission attorney known as the “Pension Detective” for conducting $1 trillion in forensic investigations of the wealth management industry—says investment performance is so often downplayed, if not ignored, in debates about public pensions.

“There are three key drivers of a pension’s health,” he tells San Jose Inside. “There’s how much goes into the pot, how much goes out of the pot and how it’s managed. If any of those three are off or amiss, it suffers. Money in, money out is routinely debated because taxpayers don’t want to put more money in and there’s some belief that too many benefits are going out. But the single most important and least discussed element is the management of the money in the pot.”

What he’s found with government pensions in the US and abroad is “gross malpractice generally practiced.” It’s business as usual, and phenomenally profitable—at least for the people collecting the fees.

If the gamble paid off for the pensions, that would be one thing. But both San Jose plans consistently fare worse than virtually every peer group in California, losing out on several hundreds of millions of dollars in returns they would have realized had they met their own rosy projections—let alone performed on par with the S&P 500.

Yet while politicized debate over those 2012 pension cuts thrust San Jose in the national spotlight, talks about high fees and bad investments remain relatively muted. In the past few years, however, some local officials have attempted to nuance to the conversation.

A Closer Look

Mayor Sam Liccardo devoted a portion of this year’s budget message to what he calls a troubling trend favoring “high-fee, management-intensive alternative investments such as private equity, real assets, private debts and hedge funds.”

It’s an issue he began digging into more deeply after voters ratified the pension settlement on the November 2016 ballot as Measure F. A few months later, Liccardo requested an audit of the funds’ fees. The resulting assessment was eye-opening. It showed how San Jose’s pensions have long underperformed comparative plans and saw combined net losses from 2014 to 2016 of $120 million. It also found that the Office of Retirement Services lacked clear policies for holding money managers accountable.

Subsequent research by Stanford University Institute for Economic Policy Research affirmed those findings. As did a new Santa Clara County Civil Grand Jury report.

“The data shows that over the last 10 years, the San Jose plans’ returns were consistently lower than 99 percent of its peers,” grand jurors write. “Police and Fire did slightly better in 2018, at 91 percent lower than its peers. Over the last 10 years, the investment policy benchmarks generally ranked in the lowest quartile, reflecting the risk-averse approach of plan investment. The data also show that the San Jose plans consistently underperform their investment policy benchmarks. This indicates that the active management of funds did not serve its purpose of outperforming the market.”

In the same document, jurors cite a consultant’s estimate that the city would save taxpayers $20,000 for every $1 million reduction in investment fees.

“The most basic tenet of prudent investing is that you focus on costs because it’s the only thing you can control,” Siedle says. “But that simple lesson is still not well understood.”

Reed didn’t respond to a request for comment by press time. Matt Loesch, who helms the federated plan board, says he’ll withhold judgment until his fellow trustees have a chance to officially discuss the civil grand jury findings when they meet in August.

“But I can say that we take this stuff seriously,” he offers in a recent phone call, “and if there are things that we should be doing or could be doing to better administer the plan, then we’re open to those recommendations.”

Office of Retirement Services CEO Roberto Peña says something similar. “The ... boards haven’t had a chance yet to review and discuss the report,” he replies to an emailed request for feedback. “In the meantime, we appreciate the work and effort by the grand jury on reviewing the plans and take very seriously their findings and recommendations.”

Though its investment performance ranks in the bottom percentiles among like plans, San Jose’s overall pension predicament is hardly unique.

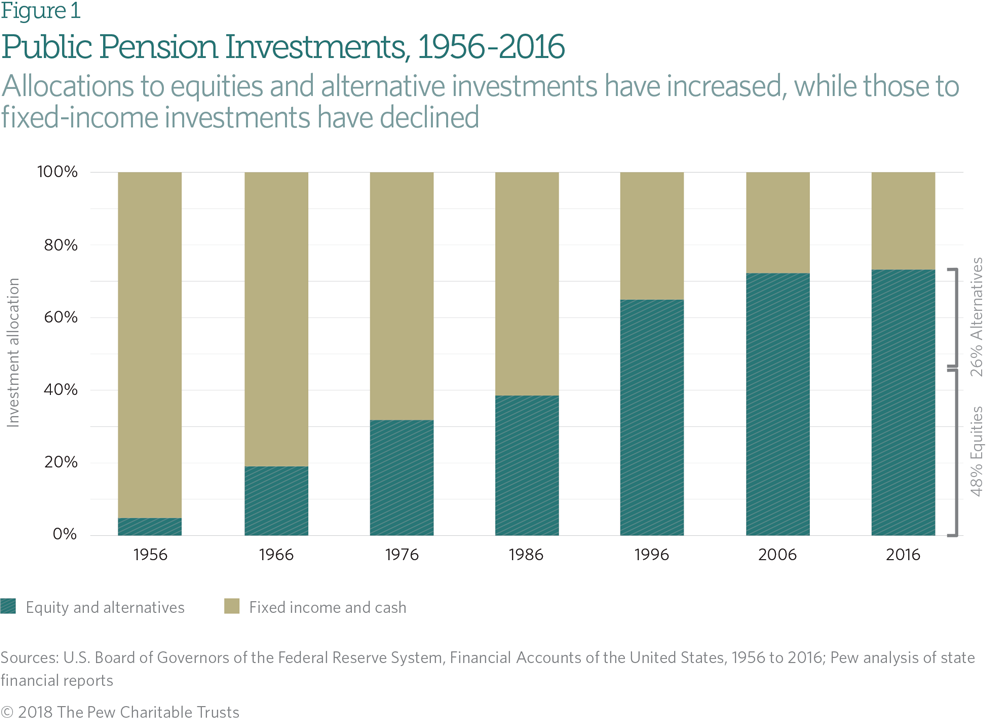

Until the 21st century, the vast majority of public pensions invested primarily in stocks and bonds. Alternatives averaged about 5 to 6 percent of public pension investments through the 1980s and ’90s. But as pension administrators tried to make up for persistent shortfalls, they grew increasingly desperate, moving trillions of dollars to hedge funds and private equity managers.

These days, public pensions in the US spend more than $2 billion a year in fees on exotic investments to boost returns. While equities and alternatives can provide higher financial returns, they’re also vulnerable to market volatility. A 2018 review by the Pew Charitable Trusts of the nation’s 73 largest public plans, which collectively bank about a quarter of their assets on alternatives, the gambit hasn’t paid off.

Nevada’s state retirement system has become a model outlier for bucking the trend, accruing above-average returns from a traditional approach to pension stewardship. About 85 percent of Nevada’s $45 billion fund is invested in low-cost index funds run by 10 wealth managers. San Jose, by contrast, parks half its $6 billion in assets in alternatives juggled by 70 investment managers and sees subpar returns.

“With investment fees about one-seventh the average public pension, the Nevada Public Employees Retirement System provides a compelling strategy of reducing investment costs to increase investment returns,” the recent civil grand jury notes.

Expertise Bias

Liccardo suggests—and Siedle agrees—that the composition of San Jose’s pension boards might have something to do with the city’s massive shift to alternatives in the decade that followed the subprime mortgage crash.

Two years before Reed’s pension-cutting overhaul made it on the ballot in 2012, he championed another pivotal change to the city’s retirement plans. Under ordinances adopted by the City Council in 2010, San Jose would replace elected officials on its pension boards with people who work in the financial industry. The other half of the boards would stay the same: employees and retirees elected by their colleagues.

The restructuring aimed to prevent conflicts of interest by removing politicians potentially beholden to unions. But it apparently opened the door to a new kind of conflict between expert appointees and their peers in the finance sector, and precipitated San Jose’s ensuing move toward costly, opaque investments.

“Academics have long speculated about the likelihood of a widespread bias in the industry to prefer higher-fee, active investment approaches despite the evidence of inferior outcomes, perhaps because decision-makers tend to share the same education, career paths and social circles as those directing actively managed funds,” Liccardo reflected in the 2019-20 spending plan he released in March.

Still, the consultants who profit off the risk have the ear of the folks in charge of the Office of Retirement Services, most notably its Chief Investment Officer Prabhu Palani.

Though the department ostensibly took a more risk-averse tack in the past few years, its pension boards mulled the idea of creating a venture capital portfolio as recently as a joint meeting with the City Council this spring. And about five months before that, they fielded a pitch from consultant Ashby Monk, of the Stanford Global Projects Center, about leveraging the city’s aspirational standing as the Capital of Silicon Valley to act as an angel investor by backing seed companies.

Councilman Johnny Khamis, a non-voting member of the police-and-fire board who attended the Nov. 5 meeting with Monk, expressed willingness to take on more risk. But he said he has doubts about how it would go over with his elected colleagues. “My only concern is how do you coach this politically?” he asked.

Even an industry appointee on the board—Ghia Griarte, co-owner of Ponte Partners private equity firm—balked at the idea because of the high failure rate of new businesses.

Monk replied that they don’t have much choice but to up the city’s contributions, cut employee benefits or make up for the shortfall by betting on alternatives.

“The only way you invest yourself out of it,” he advised, “is by taking on more risk.”

In other words, exactly what got San Jose into this mess.

Thank you, Jennifer, for finally revealing the truth about former Mayor Reed’s misplaced attack on San Jose employees as the scapegoats for the City’s mismanagement of the employee pension funds. City employees’ attempts to reveal the truth were stifled by the Mercury’s editorial staff who hailed Reed as some type of visionary reformer. All that Reed’s misdirection of voter ire at City employees accomplished was to drive the most efficient and effective City staff to the greener pastures of other cities who wisely chose not to attack their employees. The only good that can come out of this travesty is that San Jose can become an example of what not to do. Unfortunately San Jose taxpayers must pay the price for this extremely expensive case study.

Grand Jury. Now.

And people want City Hall dofusses to run a government bank?

It would probably be cheaper and more honest to dump bushels of hundred dollar bills in City Hall plaza and invite city retirees to help themselves to whatever they thought was fair.

There is bias in the industry, in the city council, in Liccardo, Jeff Rosen and so on. Most of our local politicians are East or south Asian back ground, graduated from Stanford, Santa Clara, and I other top schools, they are not talented. Most are egocentric, snobby, and love to be and be around those they consider important, Biases are the basis of this county’s corruption and failure. RECALL LICCARDO! Enough with his excuses!

Sounds like we could throw darts at an S&P dartboard over the last two years and have a better return than these poor sods. A quick question for Jennifer or smarter readers than me:

Do we have a sense of what the return was on the high-risk (and high fee) investments separate from the overall return for the pensions? The way I read the story it tells me what we:

* increased high risk investments

* paid lots in fees

* our overall return is weak.

If we could pull out precisely what the high-fee investments returned (in addition to fee cost) that would be even more illuminating.

sorry if I’m missing something.

While I can’t answer your question, $75M in fees on $5.6B of assets works out to 1.334%. Its hard to say if that’s high until we know the answer to your question. Did they return a net yield at least that much higher than an index fund or balanced stock/bond fund?

In summary, I also want to know the answer to your question so we can see if that mgt fee paid off for taxpayers or just the mgt consultants.

Rosen, no one has claimed to be smarter than you. However, as usual you are redirecting your frustration to Jennifer. While I am not in the business field, I have had businesses, restaurant, a shop…The three drivers of pension’s health, what goes in, out, and management appear to apply to the health of any business. The main message of this report, rational explained, and statistics/results’ history point to a stinky elephant in the room: MISMANAGED! Your questions should be directed to others in the city not Jennifer.

Hi Fexxnist. I’m sorry if you’re still smarting from the smackdown you got last time we crossed swords on this site. But your residual anger is getting in the way of clear-eyed reading of my post. I agree with you that the report points to gross mismanagement and i’m not frustrated with Jennifer at all. And I concur we should be directing our concern at the city, I’m just wondering if Jennifer has some extra data that would help illuminate the point. Sorry to disappoint you, but I think we agree on this one :-)

LOL it just gets better and better. The best stock market results in history and San Jose pick 70 losing horses in the money derby. You might invest in Fred Flintstones Rock Quarry, at least they know when their losing money, stop digging!

Well, I guess that plan failed miserably and now will cost taxpayers even more. San Jose politicians and staff management are not capable of making any sound financial decisions.

I don’t understand the part about a one million dollar reduction in management fees saving the taxpayers $20,000. Why wouldn’t it save them $1,000,000. Can you clarify this? Thank you.

Here’s the source: http://www.scscourt.org/documents/San%20Jos%C3%A9%20-%20Unfunded%20Pension%20Liabilities%20-%20Rev.%2006.19.19_Signed.pdf

And the verbatim excerpt: “Per the plan’s actuarial consultant, Cheiron, for every $1 million reduction in investment fees, the city contributions would decrease by approximately $20,000.”

Assuming the figures in the article are correct, the City Council imposed rules of hiring “experts” to sit on the pension boards has cost upwards of a billion dollars over the past 10 years. This does not even include the 400 plus officers that left SJPD when the “pension reform” and the hiring of financial “experts” was spearheaded by the likes of Reed, Pier Luigi, Rose Herrera, Pete Constant, etc. The cost of these officers leaving was a loss to San Jose was over $100 million dollars in training, not to mention the thousands of years of collective institutional knowledge, lost forever. Now the city is trying to play catch up and is spending additional millions in recruiting, backgrounding (which leaves A LOT to be desired), academy training, FTO training etc etc.

What happened is flat out criminal. The financial “experts” lined their pockets by buying and selling stocks, some extremely risky, just to collect the tens of millions of fees and commission each year. This is just a huge, immoral, criminal travesty committed by many, to line their own pockets by stealing from those contributing many years towards their pensions.

I can see this ending up in a Grand Jury investigation, and the city and the investment firms being on the hook for paying back hundreds of millions in fraudulent fees and expenses. Please keep looking into this, Jennifer. You have exposed what is a huge scam and the tip of the iceberg.

The grand jury just released a report that touches on the mounting fees, which is linked in the article above: http://www.scscourt.org/documents/San%20Jos%C3%A9%20-%20Unfunded%20Pension%20Liabilities%20-%20Rev.%2006.19.19_Signed.pdf

But I think it is worth following up on the potential conflicts of interest inherent in this system. And I agree that this is just the tip of the iceberg.

This is why my personal savings are in Vanguard Index funds which do not require a “manager.” Plus, Vanguard offers the lowest fees in the mutual fund industry. The founder, John Bogle (may he RIP), believed that lower fees meant more gained by the investor. Personally, I think the Stock Market (and the bond market) go up and down based not on what is actually happening in the economy, but based on the emotions of investors, thus it is unknowable and therefore unpredictable using logic. Managers’ investment decisions are at least 50% guess work. Investment firms have far more in common with casinos than they care to admit. (I once worked for a stockbrokerage firm.)

Bogle and Buffet agree. Check this out: https://www.ai-cio.com/news/warren-buffet-tells-pensions-endowments-cut-management-fees/

“Buffett describes US growth over the last 77 years. Why 77 years? That refers to when he bought his first stock: three shares of Cities Service for $114.75. And he did a little math regarding public pension funds and college endowments.

“’If my $114.75 had been invested in a no-fee S&P 500 index fund, and all dividends had been reinvested, my stake would have grown to be worth (pre-taxes) $606,811 on January 31, 2019 (the latest data available before the printing of this letter),’ he wrote. ‘That is a gain of 5,288 for 1.’

“Buffett added that a $1 million investment by a tax-free institution such as a pension fund or college endowment would have grown to ‘about $5.3 billion.’ But there’s a caveat:

“’Let me add one additional calculation that I believe will shock you: If that hypothetical institution had paid only 1% of assets annually to various ‘helpers,’ such as investment managers and consultants, its gain would have been cut in half, to $2.65 billion. That’s what happens over 77 years when the 11.8% annual return actually achieved by the S&P 500 is recalculated at a 10.8% rate.'”

Back when government pensions were moderate and reasonable they could be funded by moderate and reasonable investments. Then government pensions became ridiculously generous and could no longer be covered by prudent investment of our tax dollars. So desperation has set in and of course we can’t blame the beneficiaries and recipients of these outlandish pensions.

Noooo! It’s all Chuck Reed’s fault.

Just blame the greedy cops and firemen for the pension problems. Isn’t this the same things these supposed “Mafioso” public safety “Union thugs” have been saying all along, it’s not the pension fund, it is, like social security, political agendas and poor financial management of the money in the fund ( a massive amount which is contributed by the members themselves) that are destroying and/or damaging the pension fund. Easier just to find a convenient scapegoat though.

Chuck Reed, the gift that keeps on giving. First he destroyed our police and fire. Now we find out that his arrogance has cost pension funds millions. Then he blames it on employees.

John Galt still up Chuck Reed’s posterior. Hows the stench back there?