When the day care center for Rochelle Kent’s two youngest children shuttered on very short notice last fall, it took the single mom until spring to find a new one. To make it through those four months in limbo, the 28-year-old mother of four enlisted help from her grandma, siblings and other relatives to watch baby Ezio and and his 2-year-old sister, Ayza, so she could work overtime at a public storage company.

“It was really hard to juggle everything,” says Kent, who had to coordinate her oft-unpredictable schedule with the availability of whoever volunteered to help babysit.

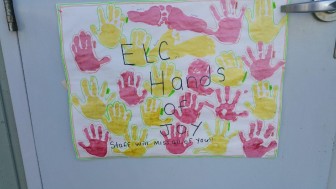

The Orchard Early Learning Center’s 2015 closure—in the thick of a school year, right before Thanksgiving—left 33 low-income families in the lurch. Kent collected more than 100 signatures for a petition to save the publicly subsidized preschool, to no avail. The doors closed two weeks after parents first heard it was at risk. On the last day, teachers had the toddlers stamp their chubby pink-and-yellow-painted handprints on a piece of poster board, which they taped to the classroom door as a parting gift.

“They loved their teachers,” Kent says. “They were inseparable.”

The Community Child Care Council of Santa Clara County, the parent nonprofit commonly referred to as the 4C Council, blamed low enrollment. But the people who work for the organization say the closure is no isolated misstep, but a symptom widespread dysfunction at what appears to be the largest taxpayer-funded nonprofit in the South Bay. Other signs of trouble: canceled grant agreements, bitter labor disputes, a longstanding failure to meet enrollment targets in a slew of programs and an eviction that shuttered yet another day care site this past year.

Artwork made by teachers and their class of toddlers just before Little Orchard Early Learning Center was forced to close.

“We’re trying to change all that,” says Mario Del Castillo, a case manager with two decades at the 4C Council under his belt. “Lack of staffing overburdens the people who work here, which affects their performance and leads them to get disciplined. If people can’t meet their performance targets, the agency can’t meet its performance targets.”

Such problems should raise the alarm at any organization, he says, but especially one the size of the 4C Council. Founded on a shoestring budget in 1971 to offer free child care to destitute families, the council achieved its tax-exempt status within a few years and went on to become the county’s sole referral agency for government-paid child care.

The nonprofit now subsidizes early education for 5,500 kids a year, according to its most recent tax records. Such service is invaluable because of the long-term benefits of early childhood education, which research has shown to improve academic performance and earning potential and reduce criminality later in life. Economically, it’s especially invaluable in the South Bay, where the high cost of living means that even families well above the federal poverty line struggle to afford day care. Yet somehow, despite having 66,000 kids on the wait-list for subsidized day care in this county, the 4C Council struggles with chronic under-enrollment.

Ninety-nine percent of the 4C Council’s funding comes from public agencies. Of its $44 million budget in 2015, about $40 million came from the California Department of Education (CDE), $2 million from the federally funded Early Head Start program, $325,000 from Santa Clara County and $2.2 million from service fees. The biggest expenditure, a little more than $29 million last year, paid for service providers. Salaries and benefits cost about $6.5 million. Though the nonprofit is subject to routine audits to make sure it sticks to the spending plan for each grant-giving agency, employees question its financial stewardship.

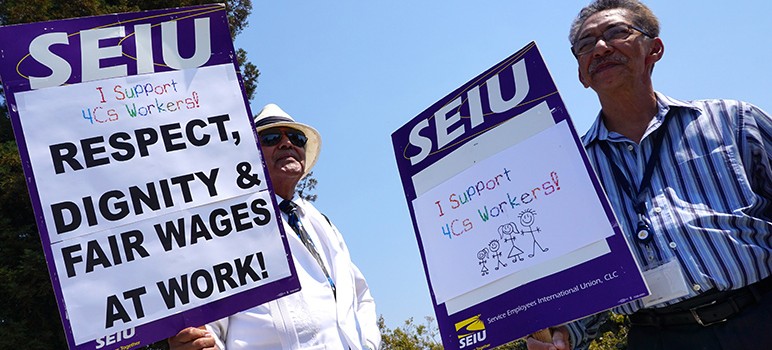

Last summer, all but 20 of the nonprofit’s 150 employees unionized to fight what they call unfair labor practices and curb runaway attrition rates that have left a 20 percent staffing vacancy. Suspicions about the agency’s finances have become fodder in more than a year of contentious labor negotiations, which—14 months and four 4Cs-hired attorneys later—have yet to result in any agreement. The man at the helm, 4C Council CEO Alfredo “Fred” Villaseñor, declined to comment for this story.

“There’s no trust,” Del Castillo tells San Jose Inside on a recent weekday while picketing outside the agency’s north San Jose headquarters. “Too much money goes to overhead, not enough to the front lines. We’ve seen too many mistakes.”

It doesn’t help that the CEO’s right-hand appointee has a few skeletons in his closet, employees say. Ben Menor—current president of the 4C Council board of trustees—was forced out as director of the Northside Community Center a decade ago after a city audit found that he misused $219,000 in public funds and a grand jury indicted him on a slew of related charges. He later pleaded no contest to felony grand theft and faced jail time until late 2008, when a judge exonerated him because he agreed to pay about $50,000 in restitution. The city, for its part, tried to retrieve its money by way of a civil lawsuit.

But records indicate that even his court-ordered payback may have come from someone else’s pockets. In 2014, one of his former colleagues—a local dentist named Antonio Abiog—sued Menor for borrowing $48,500 without any intention of reimbursing him. By the end of July 2015, Abiog won by default because Menor was a no-show. With interest, the judgment amounted to $72,816. That doesn’t sit well with the 4C Council employees.

“Our budget comes from taxpayers to help so many vulnerable people,” says Thuy Pham, a team manager who began working for the 4C Council three years ago. “We deserve greater accountability and better management.”

Rochelle Kent relies on the 4C Council for subsidized child care for her four young children. (Photo by Jennifer Wadsworth)

Menor never returned requests for comment. The nonprofit’s attorney, James Hendricks Jr., wouldn’t offer much in the way of specifics either, except to say that the council refuses to negotiate with Local 521 in the press or through elected leaders. Council spokesman Dan Orloff referred questions about the agency’s finances to the Internal Revenue Service and other outside agencies, adding that he couldn’t promise he’d be able to share much else except what’s already been posted online. Pham says management is no more forthcoming with the people who work there.

“There’s very little transparency,” she says. “We’ve seen the audits, but we still want answers. We don’t know what’s going on sometimes. There’s so much hostility, so much mismanagement and so little support that we can’t do our jobs as well as we want to.”

Around the same time Orchard Early Learning Center closed its doors over low enrollment, the 4C Council lost another 140 child care slots in San Jose’s East Side. Last fall, the Alum Rock Union Elementary School District evicted the nonprofit from a facility on Sinclair Avenue. The unlawful detainer lawsuit came barely six months after the child care council signed a 10-year agreement to sublease space from the scandal-plagued Mexican American Community Services Agency (MACSA). MACSA apparently failed to notify the school district, which violated the contract and prompted a lawsuit to kick out both MACSA and the 4C Council.

Villaseñor told the school board in January that the ouster took him by surprise and forced him to pull the plug on a $500,000 lease agreement and $70,000 in facility renovations. But the people who work for him cited the eviction as yet another sign that the agency needs to clean up its act.

“Someone clearly failed to do their due diligence,” says Dolores Bernal, a spokeswoman for SEIU 521. “Because of that, dozens of children ... were affected.”

Another lapse came by way of a smaller grant from the city of San Jose for senior health and wellness services. Incidentally, those services took place at the Northside Community Center, ground zero for Menor’s public theft scandal years ago.

The city’s Parks, Recreation and Neighborhood Services Department awarded a $35,000 grant to the council in 2013 and renewed $25,000 of it the following year. But in an email sent July 24, 2015, to 4C Council finance manager Gabriela Alvarez the city threatened to end the agreement over performance and transparency problems. The city pointed to a lack of documentation to prove that the nonprofit was serving enough senior citizens. It also found inaccurate reporting that exaggerated by 18 percent the amount of work performed under the grant agreement.

Despite those warnings and several months to take corrective action, the council still fell short of the agreed-upon benchmarks. In an email dated Feb. 12 this year, the city notified Alvarez that it would pull the remaining $5,000 of the grant and tentatively disqualify the nonprofit from future grant consideration.

“They didn’t deliver,” says David DeLong, a program manager in the city’s parks division. “They came in with a proposal that was pretty rich with activities, but weren’t able to make good on their end of the deal.”

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which funds the 4C Council’s Early Head Start programs, has pointed to similar mismanagement over much-larger multimillion-dollar grants in recent years. In compliance reviews going back to 2011, the federal agency reported a litany of violations. The nonprofit failed to enroll enough disabled children, failed to hire a licensed mental health worker, failed to screen children before a mandated deadline and failed to implement procedures to make sure it meets its contractual obligations. The most recent report in 2016 noted that those specific issues have since been resolved, but cited concerns about a lack of staffing and supervision.

While San Jose Inside has yet to obtain past-year program reviews from the CDE, the nonprofit’s biggest funder, other records indicate a years-long pattern of compliance violations. A former 4C Council computer specialist filed a wrongful termination lawsuit against Villaseñor in 2009, claiming that the state found “serious deficiency” in the nonprofit’s attendance and payment records. The suit claimed that the CDE threatened to defund the food program and mark Villaseñor unqualified and ineligible for similar grants in the future—unless he brought the house in order.

Next school year, the child care council stands to lose hundreds of thousands of dollars in CDE funding—$377,959, to be exact—for a subsidized preschool program after falling 37 percent below enrollment targets. The nonprofit reported only 31,520 out of a contractually set 50,200 enrollment days in between 2015 and this year, per the CDE.

Orloff, the council’s spokesman, says the shortfall reflects “a reduction in the available market” after the state launched a new transitional kindergarten program. Under the new rules, children who turn 5 between Sept. 2 and Dec. 2 can enroll in public schools instead of the council’s day care centers.

“So, this year, 4C Council started its marketing earlier with increased training of staff responsible for enrollment sales and marketing,” Orloff says.

Despite the so-called market reduction, there remains a huge unmet need for child care. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, roughly half the children in the state come from families in or on the verge of poverty.

A 2016 report by the Right Start Commission—a group of Bay Area lawmakers, academics and company executives—found that 70 percent of families with children aged 6 years and younger cannot afford the average day care costs of $10,000-plus-a-year per kid. Yet many working families who make too little to pay out of pocket make too much to qualify for state-funded subsidies like those offered through the 4C Council.

A bill penned by Assemblyman Rich Gordon (D-Menlo Park) seeks to change that by authorizing a pilot program in Santa Clara County to allow local flexibility in setting eligibility criteria, fees and reimbursement rates. Gov. Jerry Brown has until the end of the month to act on AB 2368, which was co-authored by Assemblyman Evan Low (D-Campbell) and state Sen. Jim Beall (D-San Jose).

Even if a family does qualify, however, with only 300,000 subsidized slots available in the whole state, demand far exceeds supply. As a result, according to the Right Start report, a million children are relegated to unlicensed and unregulated day care settings.

All of which makes any cuts in local subsidies a huge loss, says Kent, who still relies on the 4C Council to watch her kids so she could keep her job and provide for her family.

“I don’t know everything going on behind the scenes,” she says. “I want to know I can trust them to take care of things.”

> The Community Child Care Council of Santa Clara County, the parent nonprofit commonly referred to as the 4Cs Council, …. . But the people who work for the organization say the closure is no isolated misstep, but a symptom widespread dysfunction at what appears to be the largest taxpayer-funded nonprofit in the South Bay. Other signs of trouble: canceled grant agreements, bitter labor disputes, a longstanding failure to meet enrollment targets in a slew of programs and an eviction that shuttered yet another daycare site this past year.

It was a wonderfully progressive idea advocated by people who really cared.

What could possibly go wrong?

Boondoggle! Why are the employees not bonded?

This is a case of the felonious fox guarding (raiding) the henhouse!

The lack of qualifications and vetting of employees leaves the taxpayers subject to liability.

SEIU Bulls**t = trouble ahead.

How did we let these Republicans run the 4Cs Council? Wait, why not call it 5Cs? Those flat-earthers a d their crazy names.