Not a day goes by when Brandon Alvarado doesn’t encounter something or someone blocking downtown San Jose’s new protected bike lanes. Trash bins. Idling Uber and Lyft drivers. Package courier vehicles. Moving vans. Linen and beverage delivery trucks. Bird, Lime and Jump scooters. VTA buses. Even police cruisers.

Just weeks ago, a motorist almost started a fight after the bicycle mechanic snapped photos of a car impeding a bikeway by the Adobe tower off of San Fernando Street. All too often, Alvarado says, drivers get verbally or physically threatening when he politely informs them of his right to a clear bike route.

For Kelly Snider, a land use consultant and lecturer at San Jose State University, the barriers installed along 20 miles in and around the city’s central district have brought some relief. But she, too, has seen more than her fair share of tense exchanges with scofflaw motorists. “I will go up to the driver’s side if there’s someone in the car and I’ll knock on their window and say, ‘You can’t be here, you’re illegally stopped here,’” she says. “I get yelled at all the time for being perfectly legal in the bike lane.”

That’s after San Jose painted its bikeways bright green and buffered them with matching plastic posts, new lane striping and signage and parking moved from curb to mid-street to clear the path for cyclists. While only 1 percent of trips in San Jose are made by bike, the city aims to boost that rate 15-fold by 2040 as part of an ambitious effort to reduce its carbon footprint.

Yet a vocal coalition of bike advocates say that will never happen until the city figures out a better way to protect cyclists than flimsy plastic bollards, which—combined with orange plastic barricades, detours and blocked lanes from a crop of new construction—have forced people behind the wheel to navigate a baffling new landscape.

“One of the biggest reasons people don’t ride their bikes is because they’re fearful of the road,” says Alvarado, who chairs San Jose’s Bicycle Pedestrian Advisory Committee. “If we don’t do something to make them feel safer, then how are we going to meet our ridership goals?”

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) ranks San Jose as the third most perilous city to bike in America in terms of cycling fatalities and injuries. And while the Capital of Silicon Valley bills itself as one of the nation’s safest big cities, it’s growing more treacherous for people walking, biking and scooting along its sprawling tessellation of roads.

San Jose’s pedestrian and cyclist fatality rate hovers at around triple the national average and remains on an upward trajectory that saw car-related deaths overall rise by 37 percent in the past decade though the population grew less than 10 percent. Statistics for critical traffic injuries are equally jarring. In 2018, the number of people severely hurt by cars reached 195—the highest number in the past five years. The city’s death toll of pedestrians and motorists peaked at 60 fatalities in 2015—the same year San Jose joined the global Vision Zero campaign, vowing to eliminate traffic deaths through cyclist-and-pedestrian-friendly street design, public education and stronger enforcement.

In San Jose, traffic deaths outpace homicides most years. (Graphic by Kara Brown)

San Jose took the Vision Zero pledge with all the pomp of a coronation, boasting about becoming the nation’s fourth municipality to formally sign on to the international safety campaign. The unanimous 2015 City Council vote came 18 years after Sweden’s parliament endorsed the principle that “it can never be ethically acceptable that people are killed or seriously injured when moving within the road transport system” and resolved to end traffic fatalities by 2020. The initiative promoted the notion of shared responsibility between road designers and motorists to improve safety with slower car speeds and by physically dividing vehicle traffic from pedestrian zones and bicycle lanes.

Sweden’s traffic fatalities fell from 471 in 2007 to 253 in 2017 and Europe generally saw a 40 percent drop, along with a more than 20 percent decline in deadly bicycle crashes during the same period. The local trend has been less encouraging.

San Jose’s vehicle deaths now outpace homicides most years, an unusual lethality evidenced in white cross shrines surrounded by prayer candles and flowers along busy thoroughfares and crowdfunding campaigns to bury loved ones or foot medical bills for survivors. A murder rate as sharply ascendant might prompt widespread outcry. Other than occasional warnings from law enforcement for drivers to pay attention and pedestrians to look both ways before crossing, however, the city’s roadway deaths are met largely with inaction.

Five years have passed, and despite the new lanes and grand plans, San Jose has made little progress toward its Vision Zero goal. Clearly, it will take more than green paint, plastic cylinders and positive affirmations to protect lives from fast-moving metal.

“Protected bikeways are a start,” Alvarado says. “But they’re not enough.”

Zero Sum

When Jesse Mintz-Roth left New York City to head San Jose’s Department of Transportation’s Vision Zero efforts, the initiative was running up against decades of ingrained practice. After generations of optimizing San Jose’s 180 square miles for cars, reimagining the cityscape for walkers and cyclists proved daunting and costly.

In an effort to at least pick up the pace a bit, the city’s elected leaders asked the transportation agency earlier this year to estimate how much money it would need to make meaningful progress on Vision Zero. The numbers that came back were staggering.

According to San Jose Transportation Director John Ristow, completely overhauling 56 miles of the city’s most dangerous streets could cost $560 million. If San Jose took things a step further and re-engineered an additional 330 miles of major roadways, it would draw $3 billion from the city’s already strained capital budget.

Better Bikeways SJ—one of several San Jose-specific plans by which the city aims to achieve its Vision Zero goals—brought buffered bike lanes downtown and offered a workaround to the fiscal constraints. Instead of using more permanent materials like concrete for protected bike paths, the city opted for cheaper posts and paint as part of what it calls a “quick-build” strategy, which it wants to expand throughout the city.

Mintz-Roth says he worked on similar projects at his last job as a transportation planner in the Big Apple, where he also fielded misgivings from the public at the initial rollout. “Some people feel like it might be more dangerous,” he says, “but in practice I think that sort of double-take where you have to think to yourself, ‘How do I use this street?’ … slows people down.”

But Alvarado says the city needs to bolster public outreach to drivers before bringing its quick-build bike lanes to the rest of the city. “They say people have to learn to use it,” he says, “but my fear is that they build it so fast that they build more conflicts between cyclists and cars. I don’t know. I’m just not convinced yet.”

Rocky Road

What’s fueling the rise in traffic fatalities is up for some debate. After four decades as a personal injury lawyer, Michael Kelly says he’s fairly certain distracted driving is pushing up the death toll to record heights. It’s not just talking on the phone, he clarifies—simply having a handset in the car dangerously divides the driver’s attention.

“I actually think somebody ought to think about a complete bar on being on your phone while driving,” says Kelly, of Walkup, Melodia, Kelly & Shoenberger. “There is a belief that if you’re not holding your phone, you’re not being distracted. But then why are these deaths so high? We’ve electrified intersections, we’ve painted bright stripes on the roads, we’ve built these barriers, we’ve put in lights—so what the eff is happening? I don’t think it’s about visibility. I think it’s about inattention.”

Public safety officials put some of the blame on an uptick in SUVs, whose size makes them safer for the people inside but deadlier to pedestrians. The San Jose Police Department says it’s a dearth of enforcement. During the Great Recession and ensuing battles over unfunded pension liabilities, the number of traffic cops in San Jose dwindled from a couple dozen to barely a handful, a staffing level that held steady until this fall when Chief Eddie Garcia finally brought the Traffic Enforcement Unit up to 12.

California Walks—a non-profit that advocates for pedestrian-safe cityscapes—and its local chapter contend that the problem lies with poorly designed streets. “We need to invest in infrastructure,” says Nikita Sinha, manager of the Walk San Jose program. “Ultimately, if you want to see people driving slower ... you need the infrastructure to support that behavior. It’s going to come down to how our city physically looks.”

Of the 17 major streets deemed deadliest by San Jose’s DOT, most comprise multi-lane corridors with long distances between traffic signals that allow drivers to pick up velocity and posted speed limits of more than 40mph. Other risk factors, according to San Jose Walks: a lack of sidewalks, signage, bike lanes and crosswalks. Forty-three percent of San Jose’s traffic deaths and nearly a third of serious injuries happen in those 17 roadways, dubbed by DOT as “priority safety corridors,” which span a combined 70 miles.

Law enforcement data show that, by far, the most destructive prevailing factor behind the collisions is speed. The victims are disproportionately Latino and Vietnamese and skew middle-aged to elderly. The deaths of 56-year-old William Povio and 91-year-old Gerald Williams each offer a case in point. On Oct. 23, a silver Lexus plowed into Povio as he walked near First and Virginia streets in broad daylight. Just days later, a Toyota RAV4 struck Williams as he rode his bicycle left toward Capewood Drive. Both died in hospitals earlier this month, bringing the year-to-date tally of San Jose traffic deaths to 43.

The deadliest intersections tend to lie in San Jose’s downtown and East Side, where they’re concentrated in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. Between 2014 and 2018, Councilwoman Maya Esparza’s District 7, which encompasses Tully-Santee and Seven Trees, saw 52 traffic fatalities—the highest rate in the city. During the same timeframe, Councilman Raul Peralez’s District 3, which spans downtown, counted the second highest number of deaths at 34 and the most crashes at 5,544.

Despite demographic and geographic disparities in traffic fatalities, however, the city allocates $200,000 in traffic calming funds to each council district. Peralez says the city should use an evidence-based approach to budgeting for pedestrian safety by giving more money to the highest-need areas. “The way that we currently do things is not equitable,” he tells San Jose Inside, “and I don’t think that’s fair for the communities out there potentially suffering more than others.”

The costs to realize Vision Zero may seem insurmountable, but the price of inaction is greater. According to the NHTSA, car crashes in the US cost more than $870 billion a year in lost productivity, medical and legal bills and related societal and economic impacts. While driver deaths have declined as vehicles become safer for the people inside them, they’ve become more lethal for anyone in their path, turning 2018 into the deadliest year for cyclists and pedestrians since 1990.

Dark Moment

Kyle LaBlanc had no desire to ever get behind the wheel of a car. A stickler for the rules of the road and every other sphere of life, it annoyed him to no end to see so many reckless drivers. The honking, the speeding, the unpredictability of the roadways felt like chaos to his extraordinarily perceptive mind.

Gina LaBlanc began advocating for safer streets after losing her 18-year-old son, Kyle LaBlanc, in a 2016 traffic fatality at a dangerously unlit stretch of Curtner Avenue in San Jose. (Photo courtesy of Gina LaBlanc)

Public transit, on the other hand, with its schedules and fixed routes, appealed to his sense of order. Throughout high school, the San Jose teen confidently navigated the South Bay’s plexus of trains, light rail and bus lines.

He appreciated the interconnections that brought him from one point to another as he appreciated the reticulations of computer networks and electrical circuits, which he learned to build at the age of 5 with the same grandfather who taught him how to ride a bus.

For as long as anyone in his family remembered, the boy loved using technology to devise new inventions. At 17, he created his own software cloud with a dozen computers he built from scratch. His parents and little brother could tell when he powered them all up at once because the lights would dim in the LaBlanc home. “He would have been an excellent IT person,” says his mother, Gina LaBlanc. “He was my IT person. He really loved helping everybody fix their computers. He could bring a dead iPhone to life.”

Just three weeks after Kyle’s 18th birthday and about eight months before he planned to start computer networking classes at Monterey Peninsula College, a mass of steel and glass came hurtling toward him and cut that future short.

It took multiple months and lawsuits for Kyle’s parents, Gina and Steve, to piece together the events preceding the crash that killed their son on Jan. 25, 2016. They learned that Kyle walked westbound on a dirt path beneath the Highway 87 overpass by the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority station at Curtner Avenue, which has confusing crosswalks and no signs to steer pedestrians to a safer route. Recent rain muddied the path and Kyle—in brand-new basketball shoes—stepped off the curb and into the bike lane. With the lights out under the freeway, a waning moon offered the only illumination.

Shortly past midnight, a Tri-City Recovery Dodge Ram tow truck drove under the same overpass, where he merged slightly into the bike lane and struck Kyle at about 45 mph.

Paramedics rushed the boy to Valley Medical Center’s intensive care unit, where trauma surgeons undertook what Gina calls “a valiant effort” to mend his mangled body. Kyle’s parents showed up in time to take one last look into his eyes.

“I felt like he was waiting for me to get there,” Gina says. “Then his eyelids started to fall.” He died minutes later at 3am.

A day later, the city dispatched a public works crew to install new lights below the freeway. Other than that, nothing’s changed. At least two other pedestrians lost their lives in the same way in the same spot just months before and after the trucker killed Kyle.

“It’s a pedestrian trap,” Gina says, “and nothing’s been done to fix it.”

Change Makers

There are plenty of ways to curb vehicle deaths. But overhauling streets to slow traffic and get people out of their cars doesn’t exactly score a lot of political points. Just look at the backlash against the “road diet” on San Jose’s Lincoln Avenue a few years back, or more recent efforts in Los Gatos, where the southbound lane of North Santa Cruz Avenue was turned into a one-way street. Budgets restrict safety efforts at the local and state level, where highway widening and major public transit projects eat up most of the funding. Police departments say they’re stretched thin, and privacy concerns prevent many locales from installing cameras to enforce speed limits.

Diane Solomon, a local author and activist who bikes along many of those problem corridors, agrees with Walk San Jose’s stance that the city needs to reconfigure the streets and invest in more traffic signals, brighter paint, bigger signs, new lighting and traffic-slowing measures like speed bumps. “This will be expensive and unpopular,” she says, “but it will save lives.”

After years of complacency, at least the city is finally ramping up those kinds of projects. On Nov. 4, Mintz-Roth went before the city’s Transportation and Environment Committee to present the latest sobering statistics on “KSI collisions”—bureaucratic shorthand for crashes in which a vehicle “killed or seriously injured” someone. He called for more funding for data analytics and road redesigns and asked the city to form a multi-agency task force to double down on the Vision Zero pledge.

Kirsten Smith, whose dad died by a hit-and-run earlier this year, applauds the proposals but also asks what took the city so long. “Hearing that for six years you’ve seen a trend in KSIs go up … how did we let that go?” she asked at a recent public meeting. “How did no one see that for six years?”

Losing her father, Bob Lavin, robbed her of the safety she felt all her life in San Jose, she said. Multiple traffic deaths have occurred around the same Curtner Avenue corridor where police say 35-year-old Anthony Trusso, on June 28, rammed his car into Lavin during one of his daily bike rides. But a continued lack of enforcement and a dearth of cameras render it just as unsafe as the day he died, she added.

“With all due respect, my dad is not a KSI,” Smith said, addressing city staff. “His name is Bob Lavin. … So, I know you need your lingo, but he’s a person.”

Minutes later, Gina LaBlanc—who wore a pin on her sweater with a picture of her smiling son in a Captain America T-shirt—stepped up to echo Smith’s condemnation.

“I am shocked that a dangerous situation is allowed to continue and no changes have been made, as though my son’s death and life didn’t matter,” she said, holding up a blown-up version of the same photo. “This is my son, not just a data point.”

Sunday March

San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo’s cycling crash in 2018 inspired bike mechanic and activist Brandon Alvarado (right) to organize tribute rides for fallen cyclists. (Photo courtesy of Brandon Alvarado)

A self-described “cycling geek,” Mayor Sam Liccardo has long backed policies to make San Jose more bike-friendly. As downtown councilman a decade ago, he helped create the city’s Bike Plan 2020, which envisioned a 500-mile bikeway network and called for halving the number of car-bike collisions by 2020. This year, he became a data point.

When Liccardo barreled into an SUV crossing a northeast San Jose intersection on New Year’s Day, the cycling community nationwide took note. Public safety in poor, underserved areas with large immigrant populations have been historically ignored, but suburban streets that aren’t even safe for a cycling-enthusiast mayor made national headlines.

Liccardo fractured his sternum and two vertebrae in the collision, which left him wearing a brace for months. Shiloh Ballard, head of the Silicon Valley Bicycle Coalition, rode to the scene of the crash—at Salt Lake Drive and Mabury Road—to assess whether improved visibility might have prevented the accident.

Alvarado also seized on the moment as a chance to raise awareness about the dangerous state of the city’s roads. “I wrote him a card that had a bunch of bikes on it and hand-delivered it to his office,” he recalls. “It said, basically, that I hope you recover, I’m sorry to hear what happened and that I want to meet you to talk about what I could do individually to make things better.”

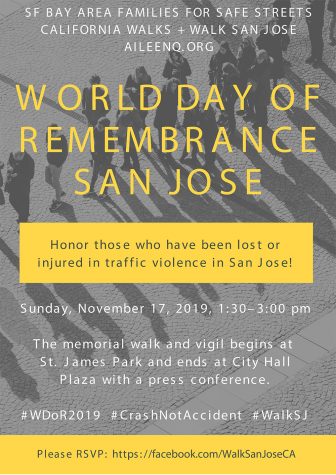

Walk San Jose will lead a memorial march on Sunday to honor the lives lost to traffic fatalities. (Source: Walk San Jose)

Liccardo took him up on the offer, granting a face-to-face klatch where Alvarado shared his idea of bringing a Ride of Silence—a nationwide ride to commemorate victims of traffic collisions—to San Jose.

Alvarado’s first Ride of Silence took place on a rainy mid-May evening in downtown and drew a few dozen participants. But what he initially planned as an annual event took on a life of its own. In the weeks after Bobby Lavin’s death, the man’s family asked Alvarado for help putting together a celebration-of-life ride.

“I jumped on it,” Alvarado says. “I’d already made a personal commitment that when somebody does have a fatality, we can have this format for a ride ready to go.”

Lavin’s surviving relatives picked a date in early August, a day before the funeral. Councilman Sergio Jimenez sponsored the Hawaiian-themed event, while Liccardo and council members Dev Davis and Pam Foley spoke and Johnny Khamis came to watch. The perambulatory tribute ended at the Lavin home, where about 50 of the remaining attendees formed a circle, held hands and joined in a traditional Hawaiian prayer.

Lavin’s widow said the gathering made her feel at peace about going to her husband’s funeral the next day.

“We can’t bring back their loved ones,” Alvarado says. “But we do want to bring these families into the conversation and let them know that we’re here for them.”

On Sunday, Alvarado will join Walk San Jose and SF Bay Area Families for Safe Streets in a World Day of Remembrance march for people killed and injured by cars. The solemn procession will start at 1:30pm at St. James Park and wend its way to City Hall, where friends and relatives of victims will have a chance to share stories of a kind of loss that’s widely accepted as an inevitability of modern life.

Last year's World Day of Remembrance procession drew scores of people to downtown San Jose to memorialize the lives of cyclists and pedestrians killed by cars. (Photo via Walk San Jose/Facebook)

A previous version of this article stated that San Jose’s traffic fatality rate was triple the national average. The story has since been updated to clarify that San Jose’s pedestrian traffic fatalities are three times the national average. San Jose Inside regrets the error.

“I will go up to the driver’s side if there’s someone in the car and I’ll knock on their window and say, ‘You can’t be here, you’re illegally stopped here”…..I wouldn’t try to be a cop without a badge and a firearm

I do the same to alert drivers about brake and tail lights not working. I guess you want a citation from a cop instead…….

I do too, if it’s safe (i.e., they’re stopped at a red light). They always appreciate it. Another community service provided by cyclists!

if you can’t tell the difference between the two interactions I can’t help you

I’ve had these things happen to me with the new bike infrastructure in downtown San José. Had a motorist become furious when I photographed his car blocking a downtown bike lane. Been blocked by a plainclothes police vehicle parked in a bike lane. Have had to maneuver around dumpsters in the bike lane.

I’m not sure the new bike lanes are working at all locations. though I welcome the experiment. The intersection of Third and San Fernando is baffling for both cyclists and drivers. You have to have your wits about you when you cross it. Riding west of Seventh Street on San Fernando Street with the cars parked out in the street can be hair-raising at intersections and with people walking around in the bike lane.

The above article states, at least twice, the importance of “physically dividing vehicle traffic from pedestrian zones and bicycle lanes,” yet there is little indication that the most vocal bicyclists want to be separated. Instead, vocal bicyclists would like to bike on streets made for cars, but preferably with cars moving as slow as bikes or, even better, without cars. It makes more sense to give bikes their own paths. In fact where this is done more bicyclists are present. (Count bikes along Los Gatos Creek Trail or along the Mountain View Stevens Creek Trail, for example.) In large-vehicle versus tiny vehicle collisions, say a 12-wheel truck versus smart car or any car versus a bicycle, the smaller vehicle almost always sustains the heaviest injury. (There are exceptions.) But who is at fault? In the following NPR article from 2011, “Cars do seem the more likely culprit since they’re bigger, more powerful … But when we looked at data from the few states where it’s available, cyclists seem almost as likely to cause an accident as motorists.” (https://tinyurl.com/yxnkspl4) In fact the City of Santa Clara BPAC heard a similar local percentage during an October 2018 presentation, and there are similar reports made to the Santa Clara Valley VTA organization. The answer is neither to outlaw cars nor bikes, but acknowledge their very real differences and to separate them.

Bikes should be completely separated with barriers from cars. Look to Shanghai and Amsterdam for examples.

The various paint schemes and obstacles used in downtown San Jose are part of the problem. Parking in the street, not along the curb, invites conflict.

First reserving 50% of the streets for 1% of the population is just wrong, it’s arrogant. Slowing down traffic in a city will create gridlock. But if your goal is to destroy the city and civilization by all means shut down the streets to cars, trucks, and buses. See what it cost is when your grocery’s are delivered by rickshaw instead Uber. San Jose is drifting backwards You can’t put in GOOGLE and expect people to arrive by steam train or horse.

Crazy is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.

Sorry but your statement is almost entirely hyperbole. 50% just for bicycles? The situation on the street is nowhere near that. Not even 1% of street space is dedicated for bicycles. Your misinformed gloom and doom is not helpful. I’d go on but I need to catch my steam train to google.

I just love bike lanes. I think when I’m president I’ll make sure all bikers don’t have to obey the law. You know, like drive on the wrong side of the street or using the pedestrian crosswalk buttons so they can proceed (IN THE CROSSWALK.) Even better not have to pay taxes like the people that drive on the road and have now been displaced by the removal of a lane just so the bikers can have an even wider lane on which to frolic and flip off the motorists. It’s just so heartening, but then I live in California, where almost nothing makes sense. You know like building apartments for two hundred families, but have parking for 80. Nah, you kidding right? No when the question was asked to the majestic pombahs of the city, we’re told it’s to INSPIRE (their word) the use of other transportation to get around. I’m done, I think I’ll just go throw up.

There’s no reason to be rude. People on bicycles are simply trying to get around – as are pedestrians, car commuters, scooter renters, etc. If there’s idiocy, it revolves around the idea that the easiest, cheapest solutions are the best – namely painting the street or slowing other vehicles to a crawl. City planners and others should remember that sidewalks for pedestrians were once an expensive innovation. (Here’s a picture of a NY City street from early 1900s, https://tinyurl.com/yjknj93o). They should plan for separated bike traffic.

Cumulus, I agree with you generally, but unless they’re cleaned regularly, separated bike routes will fill with debris. Even the bike lanes do; many are not cleaned often enough, if at all, and become full of shards of glass. I find myself having to ride in the motor vehicle area to avoid getting a flat.

BMAR3, Keep in mind that each cyclist who annoys you is not in a car to annoy you by driving too slowly in front of you. Even if bicycle traffic is only 3% of all vehicle traffic, that 3% could be the difference between getting through a traffic light in your car or having to wait through another cycle.

Here’s a picture of a separated bike lane with no debris. Note 2 lanes are together on one side of the road. (Picture taken in France.) This would work along El Camino, leaving the other side free for other uses – cafe tables, small green area & plantings, public rail transport, parking, whatever … https://photos.app.goo.gl/tWMvd7mLJHxXsb366

Its difficult to deliver packages or pick up a passenger when there’s no place to stop safely. There are trucks double-parked all over the place for that reason. I understand the green lanes for bicycle safety but its getting so constricted that there is no room for people to do their jobs. The person who called for an Uber/Lyft maybe a tourist and has no idea that on the other side of those parked cars is a green bicycle lane or even what that means. And, frankly, its also hard to balance pedestrians jay-walking, cars jumping out or stopping suddenly in front of you, bicyclists unaware of their surroundings, stop lights, stop signs, glaring headlights and frequently-changing lanes painted in the street. I think everyone is just getting tired, tired of being disrespected, tired of traffic jams, tired of clueless, selfish drivers of all modes of transportation. I also can’t tell you the number of times someone has been right in the post between my windshield and the driver-side window. Unless you make eye contact with me, don’t assume I see you.

Ooouuu – another reason for 2-way, bike lane separated from traffic on one side of street, leaving room for trucks & ubers on the other side. Everybody wins! https://photos.app.goo.gl/tWMvd7mLJHxXsb366

That’s what happens in the car-separated bike lanes in downtown San José: people wander into them without looking, and I can’t blame them, because the setup has got to be unfamiliar to many people, especially visitors. I suspect that most have no idea that they’re in a bike lane. And those right turns around the green pylons—both drivers and cyclists have to interpret a lot of data fast and transmit it from our brains to our muscles. It’s daunting.

I’m still glad that San José is running this experiment, and over the next 10 years there probably will be numerous adjustments.

Sorry pedestrians have the right of way. Bikes must stop for them just like cars have to stop for them other wise it will be just anarchy out there. Ooops’s sorry I forgot this is the Anarchy state!

According to San Jose Transportation Director John Ristow, completely overhauling 56 miles of the city’s most dangerous streets could cost $560 million. If San Jose took things a step further and re-engineered an additional 330 miles of major roadways, it would draw $3 billion from the city’s already strained capital budget.

Bike lanes are notorious welfare for the rich. 59 miles wont get SJ to 15%, 330 miles wont either. Like light rail, this is good money after bad. If SJ wants less cars on the road, significantly increase bus routes, and optimize them with a brutal hand. Bike lanes only help those who live close to thier job, which is mostly a precious few rich white men, statistically speaking.

Why do people in the Bay Area keep doubling down on ideas that dont work? Light Rail, High Speed Rail, Rent Control, CEQA, Urban Growth Bound., Bike Lanes… does the mismanagement never end?

> Why do people in the Bay Area keep doubling down on ideas that dont work? Light Rail, High Speed Rail, Rent Control, CEQA, Urban Growth Bound., Bike Lanes… does the mismanagement never end?

They’re just TRYING to be stupid because they know it offends us and because stupidity costs money.

I visit downtown San Jose every week and was initially frustrated with the change in bike lanes and curb parking. I realize now my frustration was really because I didn’t understand them. Now that I do, it makes a lot of sense and protects bicycle riders. One of my big issues which was barely mentioned in this article is the electric scooters downtown. I ride the scooters all the time and enjoy them and find them convenient for transportation. Even with these wonderful protected bike lanes, scooters continue to race up and down the sidewalks. I have been almost struck a number of times. There appears to be virtually zero enforcement of the law by San Jose Police Department regarding bicycles and scooters on the sidewalks. I regularly watch bicycles and scooters zip down the sidewalks right past several officers and not once have I seen an officer make any attempt to enforce city ordinance. It’s completely ignored. Please don’t disregard this issue any longer because someone is going to be seriously injured or killed. Police Chief Eddie Garcia I have great admiration for you, but please direct your officers to enforce city ordinances and not look the other way!

And just as an aside, the Adam Schiff hearings have been educational.

I learned a new way to say “Shut up, bitch!”:

“The Gentlelady will suspend”.

Just. Another example of a group of arrogant sociopaths enacting policy that exacerbates the very ills intended to eradicate. Zero does not equal 195.

The San Jose Bike Model is doomed to fail as it provides a false sense of security.

We’ve heard of white privilege, how about motorist privilege? Seems like drivers believe they have the right to go where they want to go as fast as possible, whenever they want. Given how congested our streets are, this results in traffic fatalities. It’s the speed of the cars hitting bicyclists and pedestrians that kills or seriously injures. Adding bicycle lanes slows motor vehicles down and saves pedestrian and bicyclists’ lives.

Motorists, you must slow down and notice bicyclists and pedestrians. My advice to complainers about the accommodations for bicyclists: Read your DMV handbook and learn the Law. Bicycles are vehicles. Bicycles have the same right as motor vehicles to be on California’s city streets. Since 2016, drivers are required to be at least three feet away from bicycles at all times. No, you don’t have more right than bicycles to take up space on the roads.

> Read your DMV handbook and learn the Law. Bicycles are vehicles. Bicycles have the same right as motor vehicles to be on California’s city streets. Since 2016, drivers are required to be at least three feet away from bicycles at all times. No, you don’t have more right than bicycles to take up space on the roads.

No problem.

“Bicycle privilege” can easily be fixed by voting a few politicians out of office.

New politicians. New laws. Bicycles back in the toy store with the scooters and skateboards.

I’ve noticed that Amazon never delivers my loot by bicycle. Nor does the trash hauler collect my trash via bicycle.

The bicycles just get in the way and clog things up.

No bike lanes. No bicycles.

No bicycles. No bicyclist whining. And betters service from Fedex and UPS.

It’s a WIN, WIN, WIN situation.

Edna,

If that is correct the bicyclist should not have special privilege’s with 50% of lanes reserved for them. They are vehicles just like cars and motorcycles, Motorcycles don’t get special lanes nether should bikes.

Ban Bikes Now, they are more dangerous than guns.

While it’s so fun to trash others,real solutions involve conversation not chest beating contests. Though debate and infantile statements boost dollars for media it is not impossible to find solutions that work for, if not everyone, then for the vast majority of people. Anyone/everyone wanting a better commute should start thinking about others who are unlike themselves.

> Anyone/everyone wanting a better commute should start thinking about others who are unlike themselves.

Very open minded and tolerant. Maybe even virtuous.

Those claiming bicycle privilege can lead the way in showing us how to “start thinking about others who are unlike themselves.”