When owners of The Reserve announced plans to oust hundreds of people from the aging rent-controlled apartments last spring, the outcry grew loud enough to make national headlines. Tenants from the 216-unit West San Jose complex who implored the city for help, however, found out that not much could be done in their defense. Local law doesn’t require landlords to pay relocation costs for taking rent-stabilized units off the market, even though it displaces an untold number of people and puts some on the street.

At Waterloo—another West Valley apartment limited to 5 percent annual rent hikes under city law—the exodus has been staggered and largely out of public view. Tenants say they’re being pushed out by retaliatory harassment and baseless evictions. The trouble started last fall, after a mysterious leaflet appeared on each resident’s car windshield claiming that the owners wanted to empty all 92 units.

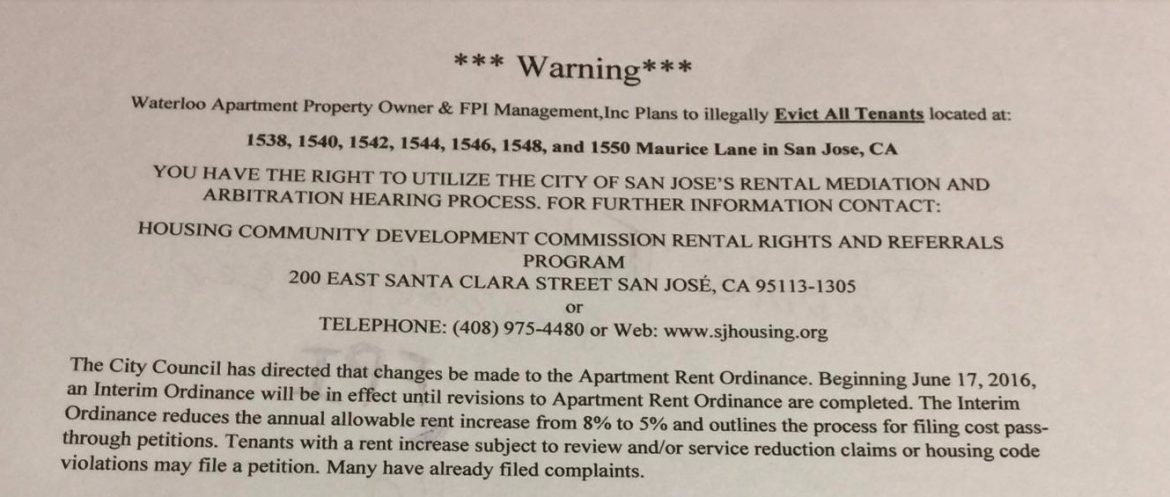

“Waterloo Apartment Property Owner & FPI Management, Inc., Plans to Illegally Evict All Tenants,” the flier stated, followed by a primer on legal rights for tenants, instructions about reporting rent hikes and service reductions, and how to file a formal complaint if any violations occur. Under San Jose’s apartment rent ordinance, the handbill noted, landlords cannot retaliate by threatening to sue, evict or terminate tenancy, harass tenants until they leave, cut services, up the rent or impose new charges.

Source: Waterloo Apartments Tenants Association

Three days later, a new and stricter property manager took over Waterloo. Residents who sought to renew their annual leases were knocked down to month-to-month contracts.

Danielle Pirslin, a three-year tenant in the unique position of having been a landlord in the past not-too-distant, decided to fight back. Armed with proof that Waterloo had been pocketing extra money by overcharging for garbage, water and sewage, she demanded arbitration. She also began organizing other tenants, telling them to take her lead and file claims with the city. The newly formed Waterloo Apartments Tenants Association has since won back close to $100,000. To battle the remaining claims, Waterloo hired an attorney, who has yet to respond for a request for comment.

Residents say that many of the predictions on the anonymously distributed flier have come true, stoking fears that Waterloo was destined for the same fate as The Reserve. Tenants who took part in arbitration say they were denied their annual lease renewals and forced into monthly contracts. Others say they were driven out by inexplicable or unjustifiable adjudicated evictions and harassed over frivolous new rules about how many plants they could set outside, whether their cats could roam the property and what time of day they could open their window shades.

Natalya Bagieva, a Waterloo tenant who suffered permanent brain damage from a fall outside her apartment door in 2014, won $3,800 from arbitration after proving that Waterloo profited as much by jacking up utility costs. In return, Bagieva says, she was saddled with a litany of new lease requirements. The 35-year-old registered nurse also filed a personal injury lawsuit against the apartment owners. In her suit, she claims that the landlord is liable for her life-altering injury because it failed to install handrails and does nothing to fix the uneven steps that tripped her up, sent her into a coma and left her permanently disabled and unable to work. For the past few months, Bagieva says, she has felt that an eviction is only a matter of time.

“It feels like sitting on a bomb,” she says. “This doesn’t feel like home to me anymore.”

All combined, these issues highlight what San Jose tenant advocates call glaring omissions from the city’s rent laws, which have inspired a historic groundswell of activism in recent months. As the number of residents evicted from rent-controlled units climbs amid an exorbitant housing market and stagnant wages, San Jose’s City Council on Tuesday will consider new ways to protect tenants and hold landlords accountable.

“This is not a political issue, this is a moral issue,” says Salvatore Bustamente, one of several people on a days-long hunger strike leading up to the vote. “Poor people keep getting evicted with no justification, just so their landlords can increase rents.”

City housing staff wants to tighten restrictions on how and when landlords can evict tenants under California’s Ellis Act. Under the 1985 state law, property owners who want to quit the landlord business can kick tenants out en masse, as long as those units are removed from the rental market. In these cases, San Jose Housing Director Jacky Morales-Ferrand proposes that landlords should be required to give advance notice and compensation for displaced residents.

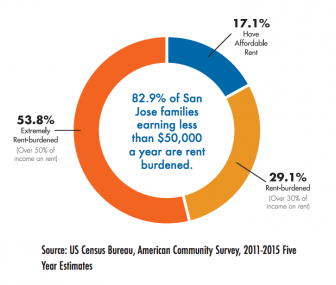

Source: WPUSA

While the recommendation is too little, too late for the 600-plus residents of The Reserve, their plight prompted San Jose to once again consider revising its apartment rent ordinance.

Another major policy change up for a vote is a ban on no-cause evictions. Despite being one of the most expensive places to live in the nation, San Jose is one of the few major California cities that allows landlords to evict tenants without any explanation.

According to a new report by union-backed Working Partnerships USA, San Jose has tallied more than 2,200 no-cause evictions since 2010—a 270 percent increase. That only counts adjudicated evictions from rent-controlled units that landlords self-report to the city. There’s no official count of how many people have been forced out of units unprotected by the city’s rent control ordinance. But the impact is measured by increased traffic congestion as people move farther away and commute from outside the region to work. The impact can also be seen in the number of people living in shelters and along roadsides and waterways. A sweeping 2015 study singled out evictions as the leading cause of homelessness in Santa Clara County.

City staff has recommended greater protections only for tenants who complain about code enforcement and safety issues. But several council members—Sylvia Arenas, Don Rocha, Raul Peralez and Sergio Jimenez—want to extend that protection to all renters. Peralez and Rocha have recommended that so-called “just cause” rights apply to renters after six months of tenancy. Jimenez and Arenas have gone a step further, proposing that the rights be automatically granted to all tenants.

“Full just cause protection for tenants would help create a more level playing field for renters caught in our city's housing crisis,” Arenas and Jimenez wrote in a memo.

Landlords have long defended no-fault evictions, arguing that tenants have enough protections under existing laws. Chung Wu, who owns a multiple apartments in San Jose and nearby cities, said the proposals up for consideration will create a hostile regulatory environment that hurts mom-and-pop landlords.

“[Although] drafted with good intentions,” Wu wrote to city officials in March, “there are specific items that carry unintended consequences and exacerbates already challenging housing market conditions.”

Councilman Johnny Khamis, who’s also a landlord, said the city’s proposal would create unneeded layers of bureaucracy for what he estimates to be a small fraction of renters. Adopting new protections would prevent property owners from cutting ties with bad tenants, he said, and would do nothing to address one of the underlying causes of the affordability crisis—a dearth of housing.

“Of course, none of the actions proposed in the Ellis Act or tenant protection ordinances will add a single new low-income unit to the housing stock in San Jose,” Khamis wrote. “Since we won't get any more housing units or lower-cost housing units with these new regulations, what will we get?”

The answer, per Khamis: micromanaged landlords, an aging housing stock and a too-powerful “Housing Tsar” at City Hall. In his memo, he dismisses the notion that evictions, displacement and substandard housing are as systemic as tenants claim.

“Staff proposes to tackle a relatively small problem with a giant sledge hammer instead of a tiny tack hammer, and increase the power of the bureaucracy in the process,” Khamis wrote. “Let's send staff back to the drawing board to find much less onerous ways to target the problems a relative few tenants have due to a few bad owners.”

His conservative council colleagues, fellow Republicans Lan Diep and Dev Davis, agree that the policy as written is unduly burdensome. “San Jose is facing a housing crisis,” Davis and Diep wrote in a joint memo. “The city should not place any more burdens, restrictions, or barriers which might discourage a landowner from increasing the number of units on the property.”

The city’s housing staff addressed that concern by proposing to put the onus on tenants, requiring them to file a formal code enforcement complaint in order to qualify for anti-retaliation safeguards. For the city’s advisory Housing and Community Development Commission, however, that doesn’t go far enough. On Thursday, commissioners voted 8-2 for universal just-cause and protections. During the discussion, the panel talked about how Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland and other major cities apply just-cause and anti-retaliation measures to all tenants, regardless of whether they file a complaint through the city and regardless of whether they live in a rent-controlled unit.

“At the end of the day, people who live in apartments don’t have the same means as the people who own them,” commissioner Alex Shoor told San Jose Inside. “The goal of this policy is to preserve people’s rights to live in a unit if they’re good tenants.”

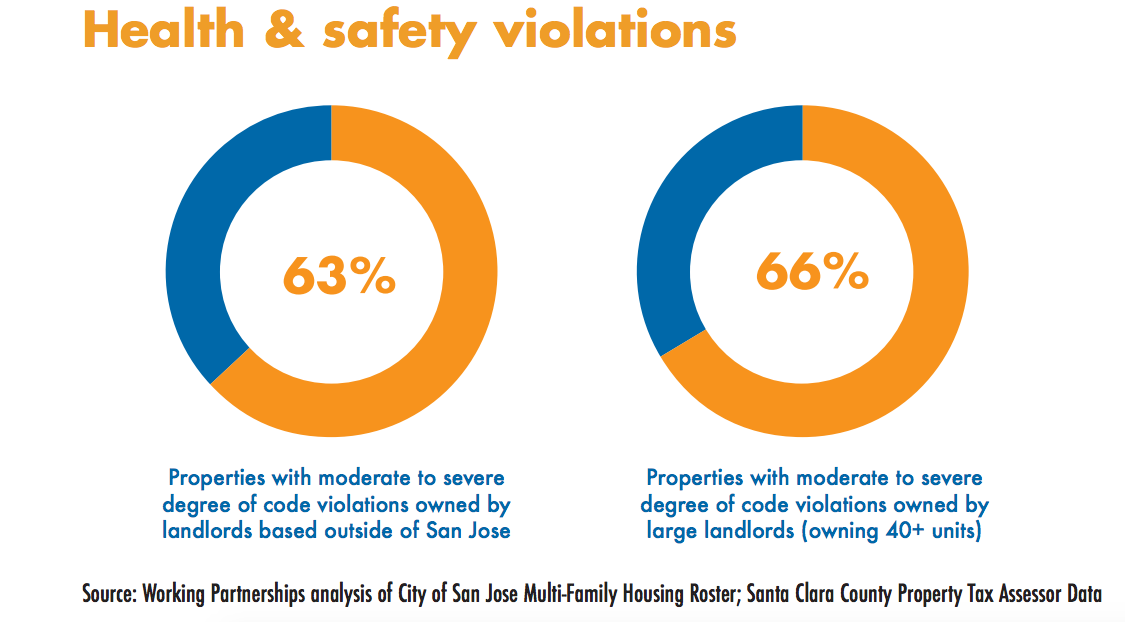

Jocelin Hernandez, a 24-year-old college student who has been fasting in support of tenants outside of City Hall, said that she hopes the housing commission vote foreshadows a similar decision from the council. She challenged the narrative that protecting tenants would come at the expense of mom-and-pop landlords. The Working Partnerships report found that of the 6,000 companies that own rentals in San Jose, 70 percent are based outside the city and account for the majority of substandard housing.

Hernandez was also critical of Vice Mayor Magdalena Carrasco for what she called a conspicuous silence on the issue until this week, given that evictions disproportionately impact minorities, women and children. Tenant advocate Shaunn Cartwright said the same holds true for Mayor Sam Liccardo, who on Monday had yet to align himself with a specific policy proposal, and Councilman Chappie Jones, whose district encompasses The Reserve, Waterloo and an unscrupulous landlord recently exposed by the Mercury News.

If city officials are serious about their claims of making San Jose a sanctuary for undocumented immigrants, Hernandez and Cartwright added, then they should consider the importance of housing for people who live on the margins.

“People have become too desperate and the problem has become too big to look away,” Hernandez says, vowing to take the issue to the ballot if necessary.

Morales-Ferrand, the city’s housing director, agreed that the community has reached a boiling point. In her policy memo, she specifically cites displacement at The Reserve last year as proof that the balance of power needs to shift more toward tenants. While the city has considered bolstering tenant protections in years past, she said, this past year has brought greater awareness of how housing instability affects the course of people’s lives.

It’s telling, Morales-Ferrand added in a phone interview, that one of the Pulitzer Prizes this year went to Matthew Desmond’s nonfiction ethnography Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. In the book, Desmond notes how evictions used to be rare enough to ignite protests. Today, however, they number annually in the millions nationwide. In his book, Desmond concludes that evictions—both court-ordered and informal—have become an inevitability for the poor and working class. Unstable housing, he found, has become not just a condition but a cause of poverty.

“Housing in San Jose is so tight, and the housing that people lose under rent control is so valuable,” Morales-Ferrand told San Jose Inside last week. “I know this from the recent experience at The Reserve. I know this from the families that are getting red-tagged out of their buildings. I know this from all the families that are losing their rent-controlled homes in Rock Springs because of the flood, from the families that have lived here for 10 to 15 to 20 years. This is their home. They have friends and family here and their kids go to school here, but it is virtually impossible for people who are being displaced to find rent for the price they were paying. The rent shock is traumatic, and it could force them to leave San Jose.”

Landlords worried about having a hard time evicting tenants should consider that just-cause laws would still give them the right to oust people for a violating their lease agreements, she pointed out.

“In this county, there is this presumption of innocence that we afford to people in the criminal justice system,” Morales-Ferrand said. “Having evidence that somebody did something wrong is incredibly important—especially in someone’s housing situation. The fact that you rent should not mean that you should face housing insecurity in such an extreme way.”

This article has been updated.

So, how is criminalizing landlords in a tight housing market going to increase the supply of affordable housing?

I’m unclear on the concept.

Good question. Most of these problems go away when you build enough housing.

This sentence caught my eye:

Tenants who took part in arbitration say they were denied their annual lease renewals and forced into monthly contracts.

“Forced”? By whom? When a lease expires, it automatically reverts to the time period of the payments. For example, if the parties sign a one-year lease and the rent is paid monthly, the lease automatically becomes a month-to-month tenancy after one year. That has been state law since, like, forever.

When these tenants claim they were “forced” into monthly contracts, whose fault is that? Is it the property owner’s? Or the tenant’s? Or the state’s?

This whole scenario is is simply rabble-rousing, since everyone admits that nothing can be done about the tenants in those particular apartments. So, is there an ethical way to deal with the problem, which is fair and equitable to all parties?

As a matter of fact, there is.

Suppose a single tenant earns $250,000 a year and has no dependents (yes, those tenants exist in Silicon Valley. They’re not even that rare). Should a law be passed exempting them from the agreements they signed? Because they could easily afford to move if necessary.

But the proposed ‘remedy’ in this article would protect those tenants, too—at the direct expense of the mom and pop landlords who make less than some of their tenants. That is neither fair nor ethical. But something can still be done to help tenants who cannot afford the new rent (and make no mistake, high rents are what this is all about).

The tenants who are truly in need can be helped fairly, just like those in need are helped with food stamps. Society (meaning the taxpaying public) subsidizes the cost of food—but only for those in need, not for those who can easily afford three square meals a day.

That is a fair, equitable, and ethical way for the city to help those who are truly in need. But we don’t provide food stamps to a Silicon Valley software engineer pulling down a six-figure income; that would clearly be unethical, since most taxpayers don’t make that much.

The rent situation is exactly the same. Some tenants need assistance. But certainly not all do. And some mom and pop owners would be hurt by a law that subsidizes the rent of well-off tenants at their expense.

It is unfair to demonize all “landlords” by confiscating their income and handing it to every tenant, no matter how much the tenant earns. Just as it is unethical to confiscate one person’s income and hand the money to a wealthier person. Doiung that is wrong. Is there any doubt?

The solution is simple, fair, equitable, and ethical: society (meaning the city’s taxpayers) should subsidize needy tenants, just like taxpayers subsidize the needy with food stamps. Only those tenants in real need of assistance would be helped—not by confiscating another individual’s earnings, but providing assistance from the city’s general fund.

That way the city would be helping only those in need—and it would avoid the unethical situation of forcing a small subset of the population to arbitrarily subsidize a much larger group, regardless of a tenant’s income.

Of course, we live in a democracy, and voters might not approve of additional demands on the city’s tax base. But if City Council members are afraid of doing the right thing, maybe ‘we the people’ need representative with a backbone—and a moral compass.

Caving in to rabble rousers when there is an ethical course of action available recalls Pontius Pilate’s ‘solution’. But “Give us Barabbas!” is the coward’s way out, no? San Jose is surely better than that.

I wonder who wrote that reply….

Subsidizing food stamps and housing are two VERY different things. How much do groceries cost here, and how much does HOUSING COST??? And how does that compare to the rest of the country?? Pause and ask yourself why that is. Of course the landlords would LOVE to have taxpayer money go to their pockets. Unfortunately housing in this area is such a scarce commodity, that public price regulation is warranted. Commercial building permits go out left and right for bigger, higher office space, but no new residential housing is made available. At the same time, I’m sure the English Estates neighborhood would LOVE to see this place get turned into a 4 or 5 story apartment building right in their backyard. If you can’t support new businesses with both infrastructure, AND residential housing availability, you need to turn away business expansion as well. THAT is the right thing to do (NOT giving taxpayer money to the landlords!). Of course the city can’t even do the former without raising taxes or issuing bonds! And for the later, you can thank organizations like the Greenbelt Alliance (the nor-cal version of the coastal commission) for the general lack of housing. The city can make two choices, allow growth, or squeeze everyone into a sardine can. You want your cake and eat it too.

As far as the previous poster, who obviously is associated with the owners/management, its nice to know that you think we’re a bunch of blood-thirsty Jews.

I think you bring up some good points. But unfortunately, trying to craft legislation that addresses this leads to the micromanaging of landlords talked about in the article. That ultimately hurts tenants and landlords alike.

The best solution is to build more housing. Interestingly, these articles never address the NIMBYs and bureaucratic rules and regulations that prevent new housing stock from being built and/or make it more expensive.

> For the city’s advisory Housing and Community Development Commission, however, that doesn’t go far enough.

I think I would like to be an “advisory commission”. Does anyone know how to go about doing this?

I think I’ll be the “San Jose Advisory Commission for Unsolicited Advice”. I assume I’ll get a car and an office and meal vouchers. Correct?

Democrats unveil plans for “rent-stabilized units”:

https://goo.gl/OcTcux

> “This is not a political issue, this is a moral issue,” says Salvatore Bustamente, . . .

Doesn’t this violate “separation of church and state”? The ACLU will be outraged.

I’ve been evicted by property tax and sales taxes which are among the highest of any city in California.

Thank you for sharing your story with others