It can take up to seven hours to collect evidence of rape. The process involves poking, prodding, swabbing and photographing victims, who are told to show up to the exam unwashed and in the same clothes they wore at the time of the assault. The ordeal is painstaking and invasive, rendering the victim’s body a crime scene.

Yet advocates say justice is delayed for an untold number of sexual assault survivors in Santa Clara County, as cases remain untested, sitting on shelves in evidence lockers.

For some South Bay cities the number of unanalyzed rape kits can be counted on one hand. At other agencies, they number in the dozens. For the San Jose Police Department (SJPD), it could be in the hundreds, but it has no plans to tally its backlog before 2012.

In 2013, an ABC7 report found that the city’s backlog totaled more than 1,800. It’s unclear how many of those untested kits still languish on shelves of evidence lockers because they’re unaccounted for in SJPD’s five-year-old reporting software, Versadex. Since Jan. 1, 2016, local law enforcement agencies have had a 20-day deadline to submit evidence to the county’s Crime Laboratory, which then has four months to process and upload it to a national FBI database called the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS).

Overseeing a city of a million people and handling the vast majority of sexual assault cases in the South Bay, SJPD puts its backlog tally at 44. But the department’s own records show that the actual number of untested kits as of this month comes to 99.

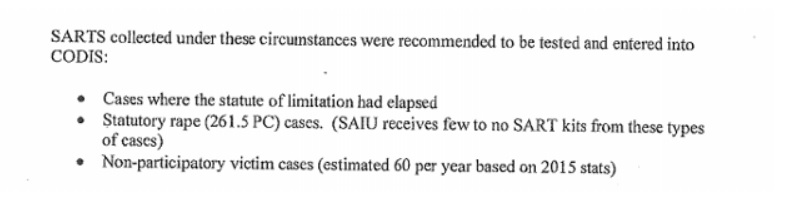

Many of the 55 kits that aren’t counted as part of SJPD’s current backlog are labeled anonymously, with numbers instead of names, because victims have refused to press charges. In California, victims that submit to these Jane or John Doe kits have two years to decide whether to press charges against the attacker. In some states, they have just two months. SJPD fields about 60 such cases every year, which it recommends but does not mandate for testing.

Source: SJPD

There are other reasons SJPD withholds rape kits from analysis, including if an investigator determines that the claims are implausible or if the victim recants.

Source: SJPD

Lt. Jason Ta, who’s in charge of SJPD’s Sexual Assault Investigations Unit, defends the department’s decision to not test all rape kits, saying it’s important to give victims a sense of control over their case. “We have some victims that come forward and they do not want their names or anything associated with their identity in a police report,” he says. “By law, we can’t force them to give us their names. Victims do have rights, too … and that is their right whether or not they want something tested.”

Not everyone agrees. Ilse Knecht, a policy director for the Joyful Heart Foundation—an advocacy group that’s pushing agencies to end their rape kit backlogs—says that every victim should choose their own path to justice, but the fact that more than half of SJPD’s untested kits in the past few years are anonymous is problematic.

“It looks like about half were tested and half of of the victims didn’t want to cooperate,” Knecht says. “That’s a red flag. When you have half of them opting out of the criminal justice system, that’s not a good sign. That’s something you need to check out.”

Demanding an end to the backlog is about treating sexual assault as seriously as other violent crimes, Knecht says. It’s also about finding serial offenders, she adds, and exonerating the falsely accused.

The U.S. Department of Justice estimates of the number of untested rape kits nationwide amounts to about 400,000. In California, organizations lobbying to end the backlog put the number somewhere from 9,000 into the tens of thousands. In Santa Clara County, estimates vary depending on an agency’s policies and software for classifying evidence.

A survey by this newspaper of each law enforcement agency in the South Bay revealed that policies about tracking untested rape kits vary. Not every untested rape kit is considered part of an agency’s official backlog, and not everyone can agree whether each and every kit should get analyzed in the first place.

Palo Alto police have managed to submit every single kit to the crime lab, according to Lt. Zachary Perron. “Since we are such a small agency, we have very few [sexual assault] kits that we collect and process every year,” says Perron, whose agency polices a city of about 70,000. “We have never had a backlog.”

Morgan Hill and Milpitas—cities of 75,000 and 45,000, respectively—have also submitted every kit for testing.

“That’s a big priority for us,” Milpitas police Lt. Raj Maharaj says.

Sgt. Carson Thomas, of the Morgan Hill Police Department, says his agency deals with about a dozen sexual assault cases each year. “All our kits are at the lab,” he says. “Getting one of these kits done is a pretty invasive process, so we want to make sure that if a victim goes through that, we’re analyzing that as evidence. Whether they want to press charges after that is up to them, but we work with them through the whole process, so that five months, six months down the line, we’re in a position to act on that decision.”

Police in Cupertino, Los Altos Hills, Los Gatos, Saratoga and San Jose State University each count one to three untested kits in the past 20 years. Other local cities report considerably larger tallies, however. The Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Office, which polices all unincorporated parts of the region, counts 93 untested kits, of which 91 have been investigated and closed. One kit from 1992 remains unaccounted for and another from 1993 remains unresolved.

Mountain View, a city of 78,000, counts 26 untested kits. Sunnyvale’s Capt. Shawn Ahearn reported 189 untested kits going back 20 years, and two since 2016 for the city of 150,000. Since 2016, Sunnyvale has booked 19 kits to meet statutory submission requirements, the city’s records manager Pamela Healy says. “Of those, 17 were submitted, and two were not, as they were for unfounded cases.”

In Campbell, home to 42,000 residents, police have 20 untested kits. Gilroy, a city only slightly larger, has 134 kits logged into evidence. Thirty-four of them remain untested for a variety of reasons, and most of those kits pre-date 2010.

“I realize that some people may say, ‘send them all in for testing,’ but in a lot of cases the victim may know the person that assaulted them, and they’re not in a state to want to pursue that,” Gilroy police Capt. Kurt Svardal says. “So we do respect their wishes.”

For some jurisdictions, San Jose Inside was only able to obtain data from last year. Out of 14 rape kits submitted by the Santa Clara police in 2016, one remains untested because police say the victim declined to cooperate. That same year, Stanford University police submitted four rape kits to the crime lab and withheld two, citing the same reason.

Assistant District Attorney Terry Harman says law enforcement agencies in this county submit every test that needs to be tested.

“The numbers show that we’re handling sexual assault cases in the manner prescribed by law, and that conform with community expectations,” she says. “If it’s not being tested it’s for the right reasons. … The way the backlog has been described in other counties, it gives the impression that crimes are not being solved that could be solved if not for the testing of the [sexual assault] kit. That is just not the situation here in this county. If there is a stranger rape, for example, that kit is analyzed immediately, for immediate results.”

"Santa Clara County has no untested rape kits"-@SantaClaraDA #inforumsf #sexualassault

— INFORUMsf (@INFORUMsf) August 17, 2016

A bill working itself through the state Legislature aims standardize reporting requirements. AB 41, a proposal from Assemblyman David Chiu (D-San Francisco), would force all local law enforcement agencies and forensic labs to tell the state Department of Justice how many rape kits they collect. It would also require the agencies to state a reason for eschewing forensic analysis, and the attorney general would annually provide the information to lawmakers.

In addition to Chiu’s proposal, California lawmakers have introduced two other rape kit reform bills. AB 1312, co-authored by state Sen. Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) and Assemblyman Evan Low (D-San Jose), would strengthen survivors’ rights to know about the status of their rape kits.

Low’s other bill, AB 280, would add an option on income tax forms for people to donate money to reduce the backlog. He proposed the legislation because of concerns in law enforcement that new deadlines and reporting requirements on rape kit testing would overwhelm already under-resourced police agencies and crime labs. Each kit costs roughly $1,000 to process, although most of the South Bay agencies San Jose Inside interviewed say money isn’t as much of an issue compared to other jurisdictions.

“Frankly there shouldn’t be an excuse for not testing every kit,” Low says. “I don’t want us to say that justice will have to wait because of a lack of funding.”

Janet Henderson, who leads a local support group for sexual assault survivors, says she’d like to see even anonymous kits tested because they could help police identify serial offenders. In Cleveland, Detroit and Memphis—cities with some of the biggest backlogs—testing previously unanalyzed rape kits helped police identity more than 1,200 serial rapists who committed crimes across 40 states, the Joyful Heart Foundation found.

Having a policy of testing every single kit would also justify the often-traumatic experience of undergoing the evidence collection exam, Henderson adds.

“I think it would send a message to survivors that they matter,” she says. “It would send a message to perpetrators that they’re accountable as well.”

This article has been updated.

Great work on this non-story.

> Great work on this non-story.

There’s a story here, but Jennifer is probably too much of a generational newbie to realize what it is.

Why is there so much more “rape” today?

Hint, rewind back to the nineteen sixties and the so-called “sexual revolution” and “woman’s liberation”.

“Peace and love, man”.

“If it feels good, do it.”

“You know.”

So your saying that women’s liberation (ie women’s rights) is the cause of increased incidents of rape?

Yes.

Can you figure this one out or do you need an explanation?

Let’s continue to pretend the claims of sexual assault victims are deserving of anything close to the face value of other serious felonies, that way we can keep the myth of the “rape culture” alive and exciting the delusions of our growing population of psychologically-dysfunctional females. Outright fabrication, self-delusion, stupidity, and tantrum are the likely culprits behind the backlog, just as they are in other false charges females routinely lodge against men.

Rather than see in these untested kits justice denied, I see in them the faces of innocent men who might otherwise have found themselves in court confronted by a sobbing, modestly-attired nut case, a rape center zealot, and a deputy DA smelling blood in the water.

Who will advocate for theft, burglary and/or fraud survivors? Those cases are virtually unworked- in any fashion whatsoever…

Messed up my life in 2008 never got suspect they always never got back to me

Police labs shouldn’t be allowed to test drug samples until they’ve tested all their rape kit backlogs. Prosecuting violent crime needs to be a higher priority than prosecuting people for using politically incorrect substances. Way too many of my friends and yours have been raped, sometimes by people they know, sometimes by strangers.