Seated in an operating room at Good Samaritan Hospital, I slip my middle finger and thumb into the arms of the da Vinci surgical robot. I lean forward, my eyes line up with the lenses and I hear three soft beeps. I now have control of the robot across the room. As I rotate my hands, the robot’s arms swivel effortlessly, side to side and up and down, with a range of motion that human wrists weren’t designed for. We’re ready for surgery.

Standing at a monitor next to the da Vinci, a clinical rep for Intuitive Surgical uses her finger to circle one of the cones on the screen. A small rubber band has been placed over the top of the cone and she tells me to lift it off. I move clumsily toward the band, hitting almost everything in my way. If the cones were a living and breathing patient, she would be hemorrhaging blood. I try to pick up a penny and bump more cones, and I think about how easy it would be for all of this to go horribly wrong.

Doctors are praising da Vinci robots at medical schools, community forums and county fairs. Hospitals hold press conferences when they buy a new system and a parade of companies, including Google, are scrambling to become the next name in surgical robots. Intuitive Surgical, the Sunnyvale-based creators of the da Vinci, raked in $2.13 billion last year, and saw 9 percent growth worldwide in procedures. But there’s another reason everyone from patients and doctors to Silicon Valley save-the-world types want in: Surgical robots are the future.

It’s not unreasonable to imagine—it’s expected, actually—that surgery will soon become automated, eliminating human error and saving lives. A human touch in the operating room will become as rare as a hand-delivered message. But using one of these robots provides a glimpse into a complicated future we don’t yet fully understand.

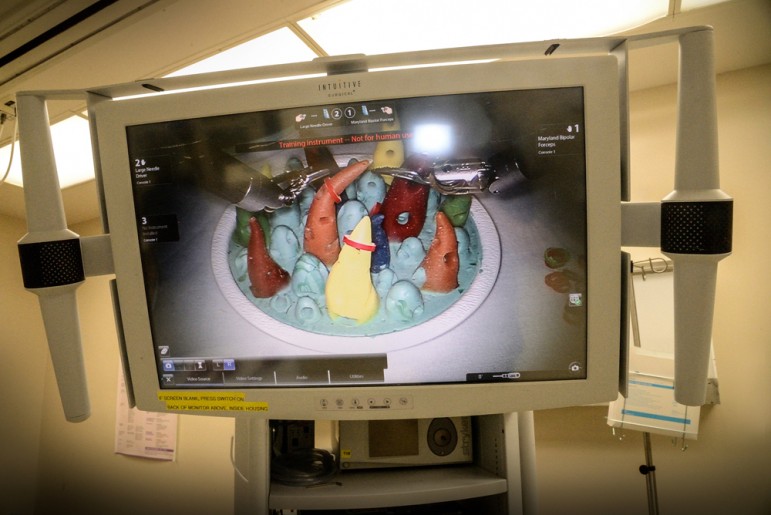

Remote controls allow doctors to train for robotic surgeries by picking up items and removing rubber bands from cones. (Photo by Greg Ramar)

Race for Recovery

Michelle Miner considers herself an exceptionally healthy person, and she looks it, too. At 51 she’s fit, has a head of dark hair, large, expressive eyes and a bubbly nature. Over the years she’d never had an IV, epidural or been under anesthesia. But by her late 40s, she suffered from uterine fibroids, causing her uterus to swell to the size of a six-month pregnant woman’s.

Miner feared not only a surgical procedure but also its consequences. Her husband had recently lost his job, and as a self-employed architect she couldn’t afford the six-to-eight week hysterectomy recovery time.

She went to see her doctor, Kristine Borrison, and noticed a pamphlet about the da Vinci robot in the waiting room. It touted shorter hospital stays, less blood loss, better pain management, smaller scars and faster recovery. Borrison estimated that the da Vinci could speed her recovery by several weeks.

Miner woke up from surgery to an anesthesiologist asking her to rank her pain. She was confused—had the surgery actually been performed? “I had zero pain,” she laughed. Motrin for the first 24 hours, and Miner was back at work full-time in just three days.

Borrison acknowledges that Miner’s recovery was unusually fast. But shorter recovery times are just one reason that approximately 235,000 gynecologic surgeries were performed by a da Vinci robot in 2014. That accounts for almost half of the da Vinci procedures last year.

Borrison did the first robotic hysterectomies at El Camino Hospital in Los Gatos and at Good Samaritan Hospital in San Jose, where she is now the medical director of robotic surgery. She estimates that she has performed more than 300 surgeries since 2009. Of those, only two were non-robotic.

“I’m really interested in trying to get fewer and fewer large incisions for hysterectomies,” Borrison said. She noted that she is compensated equally for open, laparoscopic or robotic surgery, so there’s no financial incentive to promote one over the other. “Your recovery the next morning is why I do it.”

Robotic surgery debuted in 1985, when the PUMA 560 robotic arm placed a needle as part of a brain biopsy. Two years later, the first robot-assisted laparoscopy was performed. The technology has developed rapidly since then, and Intuitive Surgical currently dominates the market, allowing it to control prices. The Xi, its newest model, costs $2.5 million, with an annual service contract of $170,000 and a per-procedure instruments bill of up to $3,200. The market, however, will soon become more crowded.

In March, Google announced a partnership with Ethicon, owned by Johnson & Johnson, to develop a surgical robot. Wired reported that Ethicon will build it, while Google will focus on creating algorithms that analyze camera images to help surgeons improve. Titan Medical of Canada is in the second phase of developing the SPORT (Single Port Orifice Robotic Technology), a robot similar to the da Vinci. Expected to be market ready by mid-2017, it should come in well below competitors at a cost of approximately $600,000.

Despite all this enthusiasm about the technology, not everyone believes robotic surgery is a panacea. Some doctors and professional associations are cautious, or even dismissive toward it. The FDA has recalled numerous robotic tools due to malfunction and patient injury, and Intuitive Surgical is facing a wave of lawsuits that allege negligence, fear-based marketing and inadequate doctor training. For the time being, Intuitive has gone into a public relations lockdown.

During my visit to Good Samaritan, Davis made a point of saying she was not allowed to answer my questions. Intuitive’s media team also declined to answer all questions, after saying they would only agree to an interview via email. Even those as benign as, “Will robotic surgery become something of a specialty or the norm in all surgeries in the future?” were considered off limits.

‘Advanced Stupidity’

Dr. Ted Anderson, vice chair for gynecology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, is a cautious practitioner of robotic surgery.

“I don’t feel like it is the panacea to cure all the ills of the world,” he said in a phone interview. Anderson believes the outcomes, including recovery time, are not substantial enough improvements over laparoscopy—a manual surgical procedure that uses a scope-like camera—to warrant the higher costs, unless using a robot will make the procedure markedly easier or safer.

Anderson is a member of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), one of several professional organizations that view robots skeptically. In 2013, James T. Breeden, president of the ACOG, wrote: “There is no good data proving that robotic hysterectomy is even as good as—let alone better—than existing, and far less costly, minimally invasive alternatives.” He expressed concern over the “increased complication rate” during the learning curve and the difference in quality of care from hospital to hospital. He called for doctors to “separate the marketing hype from the reality ….”

This criticism came at a difficult time for Intuitive Surgical. An FDA inspection in early 2013 found that the company had not reported several device recalls, including defective instruments that burned patients. Intuitive’s response failed to satisfy inspectors, and a warning letter was issued in mid-2013, threatening regulatory action.

Since that time, the ACOG’s opinion has softened a bit. Randomized control trials of robotic-assisted surgeries and laparoscopic hysterectomies found only one difference: patients who chose robotic surgery had significantly longer operations. However, in studying gynecological cancers, they found that robotic surgery was significantly cheaper, mostly because of shorter hospital stays and the patient’s ability to return to work sooner. Ultimately, the ACOG committee called for more studies, as well as guidelines for training and tracking of procedures.

Surgeon competency is what concerns Anderson most about robotic surgery. He divides robotic surgeons into three groups: those who are talented and use the robot to extend their skills; those who are are adequate, and use the robot to do things they couldn’t do otherwise; and those who “got on the robot bandwagon as a marketing tool” to make their practice appear competitive.

“Those surgeons are potentially dangerous,” he said. “One of the things I always drill into residents and into my fellows is my favorite expression: ‘Advanced technology does not compensate for advanced stupidity.’”

A recent collaborative study between three universities found that of the 1.7 million robotic surgeries performed between 2000 and 2013, there were 8,061 reported device malfunctions, which injured nearly 1,400 patients and caused 144 deaths.

Picking apart who is actually responsible for patient injuries is a thorny issue in robotic surgery. As a lawyer and former co-chair of Stanford Hospital’s ethics committee, Margaret Eaton has thought long and hard about this question.

“It’s very difficult to tease apart sometimes whether or not it was improper training, it was over-marketing, it was undermining the assessment of the risk, or whether the physician was just being kind of a cowboy and undertaking something that he or she wasn’t proficient enough to do on their own,” she said.

Since 2000, 34 civil actions against Intuitive Surgical have been filed in just the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal. Of those, eight are still active, including several individual and multiple-plaintiff personal injury suits. Intuitive estimated in its annual report for 2014 that $82.4 million may have to be spent settling product liability claims.

Many of these claims are strikingly similar. One patient developed a pelvic abscess as a result of a robotic hysterectomy she had in July 2013. Another patient’s colon was perforated during robotic surgery in 2011. A third patient was burned, resulting in a uretrovaginal fistula. A fourth patient suffered from rectal laceration and perforation.

The lawsuits fault Intuitive Surgical for, among other things, product liability, negligence, inadequate pre- and post-market testing and suppressing reports of complications.

Another allegation claims the company “sold its robotic device through a calculated program of intimidation and market management,” and that they “[do] not adequately train physicians.”

Borrison wouldn’t characterize Intuitive’s approach as predatory, but she did acknowledge that they initially “got too into marketing.”

“Surgeons were very excited to learn the new technology and Intuitive was not very discriminating in who they trained in the beginning, leaving the decision to the surgeons,” she said.

A zoomed-in display allows doctors to see what they're doing with a da Vinci device from across the room, or even further. (Photo by Greg Ramar)

Training Day

The ECRI Institute, a nonprofit that scrutinizes medical procedures, devices, technologies and drugs, included robotic surgery in its Top Ten Technology Hazards report in both 2014 and 2015. The issue they spotlight is that training for robot-assisted surgery is not standardized in the U.S.

After doctors participate in Intuitive Surgical’s “Technology Training Pathway,” which includes online instruction, hands-on training at hospitals and a day-long course operating on anesthetized pigs at a da Vinci training center, each hospital is allowed to establish its own credentialing standards.

Setting national protocols for robotic surgeries would require answering ethical and logistical questions that no one seems to want to answer. What responsibility should device-makers bear for training doctors? Who would create and oversee regulations, FDA, surgical societies or someone else? Would all hospitals be required to participate?

Despite the ethical and legal issues facing robotic surgery, the field continues to grow because of its tremendous potential. Doctors as well as researchers at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) hope to someday use robots in “telesurgery,” allowing highly skilled surgeons to treat soldiers in war zones from the comfort and safety of their home turf. Research funded by the Department of Defense using a da Vinci system recently demonstrated that telesurgery free of unsafe lag time is possible up to 1,200 miles away.

The da Vinci has only been commercially available for 15 years—a blink of an eye in the history of medicine. As robotic surgery evolves to its full potential, stumbles may have to be accepted along the way. Especially when the path of progress leads to more patients like Michelle Miner, who bounce back to work, life and health in record time.

Still failing to mention that hand held lap will do the same thing. (WTF?)

ONLY COMPARING IT TO OPEN SURGERY…STILL. Shouldn’t the doctor go to jail? Shouldn’t ISIS join them for printing the pamphlet that leaves out hand held lap as an option? This is collaborating to commit fraud and unjust enrichment on it’s FACE! WTF? If you think 82 Million is a lot… wait till the jury verdicts in April – May 2016.

Automatic surgery will NEVER be.To many variables in to many DIFFERENT human anatomies to be “Automatic”. This “thing” isn’t automatic. It is a telamanipulator not a “robot”. It is “supposed to” translate the doc’s moves to tiny moves inside you. It is the software that controls this. The software is in control. Software has “bugs”. (they don’t tell you that)

They also fail to mention that ISIS requires 3 (three) surgeries SCHEDULED BEFORE they will train a doc. Who wants to be those three-YOU? NOT ME! UNETHICAL comes to mind. Do they train for KNOWN defects to occur? NO.

It’s all about the $$. Not the patients benefit or else WHY LIE / NOT GIVE ALL OPTIONS?

Thanks FDA (gamekeeper turned poacher) for this “wonderful” tool that cost HOW MUCH? Compared to hand held lap provides NO BENEFIT to the patient (only the doc and hospital and ISIS wallet’s).

Feel sick? Sick of the BULL? go to “unplug the robot ” community page on facebook. TRUTH is there.